Life Without Father : After Split, Roy Jones Jr. Fights On Without Roy Jones Sr. in His Corner

If Roy Jones Jr. defeats James Toney in Friday night’s fight at the MGM Grand, expect the ring to swell with the usual well-wishers and relatives.

Jones will want to jump into someone’s arms. He will canvas the crowd and find a man who will hoist him.

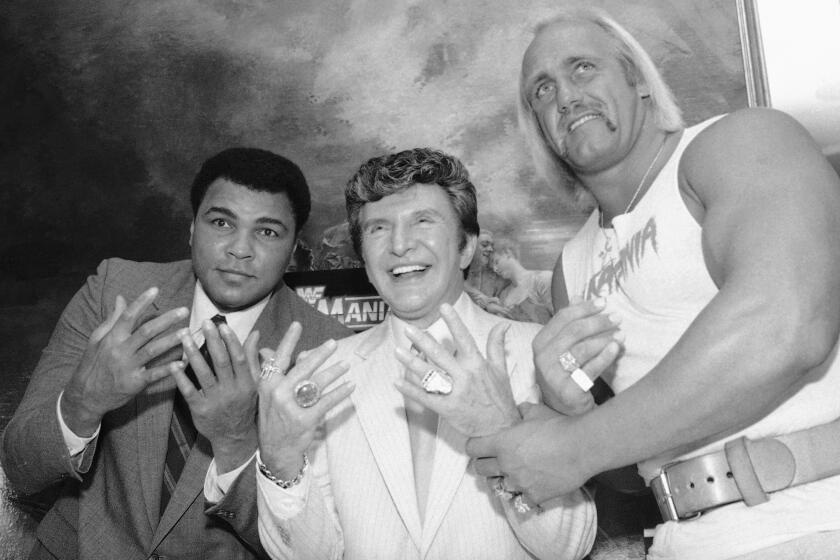

It will not be the man who reared him, trained him and tested his loyalty and resolve to no end. It won’t be the man who was in his corner for the debacle at Seoul, South Korea, in 1988, when Jones Jr. was robbed of the Olympic gold medal in his fight against Park Si Hun, the home-country favorite.

Jones won’t jump into the arms of the man who controlled his post-Olympic career and trained him through his first 19 bouts.

If Jones turns the lights out on Toney and captures the International Boxing Federation super-middleweight title, he will probably embrace Stanley Levin, a middle-aged lawyer.

This is the closest thing Jones has now to a father-son relationship.

Somewhere in Pensacola, Fla., Roy Jones Sr. will have watched the fight on pay-per-view television. Father and boxer will wait for one to call the other.

And wait. And wait. And wait.

“It’s sad because Roy Jr. will tell you his dad is a phenomenal trainer,” said Levin, the fighter’s attorney and adviser. “Roy Sr. is a good man, I like the man, I hurt for him, because I’m enjoying this. I’m sitting here where he should be sitting.”

It wasn’t easy handing dad his walking papers, but that’s what happened in 1992 when Jones dropped his father as his trainer-manager in a painful and lasting split.

Roy Sr. was last seen in his son’s corner on June 30, 1992, when Roy Jr. defeated Jorge Castro in Pensacola. On his own, Jones has gone on to win eight consecutive fights. On his own, Jones claimed the IBF middleweight title with a victory over Bernard Hopkins in May, 1993.

On his own, Jones retained his title last May with a second-round knockout over Thomas Tate, then agreed to give up the belt to move up and challenge Toney.

Jones has a 26-0 record and some say the fastest hands in the business. Unlike his opponent, the tenacious and stalking Toney, Jones is a more cerebral fighter in the mold of Sugar Ray Leonard.

Jones has done quite well since life with father. But the void is undeniable.

“Roy loves his father unequivocally,” Levin said.

Approaching the most important fight of his career, Jones would not be side-tracked this week with questions about a sore subject.

“I don’t have time to go through that right now,” Jones said. “Another time. What really happened? We fell out.”

Levin said the strain had been building for some time.

In quieter times, Jones would describe growing up under his father’s iron glove. How his dad would drop to his knees and box his young son to test his character. Roy Jr. would retreat to bed crying after some of the beatings, represented to him at the time as training.

Sometimes, if he got out of line during a workout, Jones said his father would rap him on the thighs with a piece of pipe. Jones considered running away but had no destination. Jones considered taking his life but knew that was not the answer.

Having survived, Jones acknowledges he emerged stronger and wiser. The torment no doubt made him mentally tougher as a boxer.

But he and his father were on a collision course.

“When you deal with your family, sometimes it is hard to understand,” Jones said a few weeks ago at his training camp in Great Gorge, N.J. “Sometimes one person wants to be in control and then another person wants all that control.”

Levin said he tried to warn Roy Sr. about the impending breakup.

“I’ve never done anything in the world to hurt the man,” Levin said. “I told him what was coming. I begged him. I quit drinking a while ago, but I sat in a bar and drank with him and told him.”

But it was too late.

Some would argue Roy Jr. is better off without Roy Sr. The separation certainly has not hurt Jones in the ring. Some would argue Jones would have arrived sooner on the public stage had his father not held such tight reins early in his son’s career.

Jones, 25, has fought only 26 times since turning pro in 1989 and did not claim a championship until his 22nd fight.

After the Olympics, Jones chose not to sign with one of the sport’s major promoters. Roy Sr. was left to chart his son’s slow course up the boxing ladder.

“It hurt him tremendously,” Bob Arum, who is promoting Friday’s fight, said. “You had so much network TV then, it would have given him the exposure he needed. He never got it, because it was impossible to deal with him and his father. It hurt him tremendously as far as his development as a big figure in boxing.”

Jones said he would not change the way his career has been handled.

Levin said Jones’ advancement might have been slowed, but offered that it might have been for the better.

A victory over Toney would probably send Jones soaring toward superstar status and make him, in much of the public’s mind, more than the poor kid who got cheated in Seoul in 1988.

To remind him that nothing can be taken for granted, Jones occasionally reviews the tape of his “loss” in the 1988 Olympics.

“I like it,” Jones said. “It inspires me. To me, it was one of the best performances in my career.”

The only shame now is that Jones and his father cannot share Friday together, win or lose.

Though the two rarely speak, Roy Jr. appeared to extend an olive branch when he dedicated his IBF middleweight title to his dad.

But to work, extensions have to be received.

“It’s a matter of his father being man enough to say, ‘You’re a man,’ ” Levin said.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.