New art photo books explore the famous and ‘unfamous’ among us

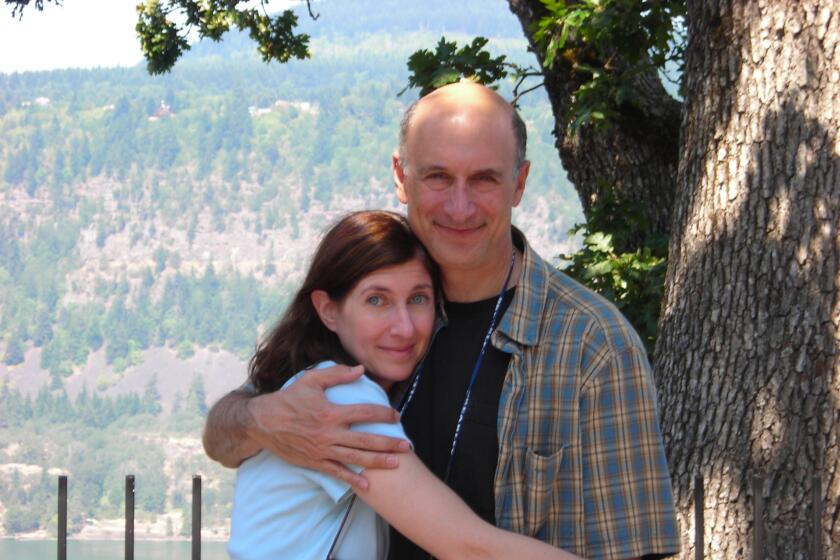

Mary Ellen Mark was equally comfortable photographing the famous and what she called “the unfamous” among us. Her travels took her from international movie sets to the Calcutta missions of Mother Teresa, from vivid high school prom portraits to a homeless family struggling on the skids of Los Angeles.

Her half-century of documentary work and portraiture made Mark, who died in May at age 75, one of the most important photographers of her era. And she returned to some subjects again and again, including Tiny, a teenage girl she met living on the streets of Seattle in the 1980s and photographed over the next three decades.

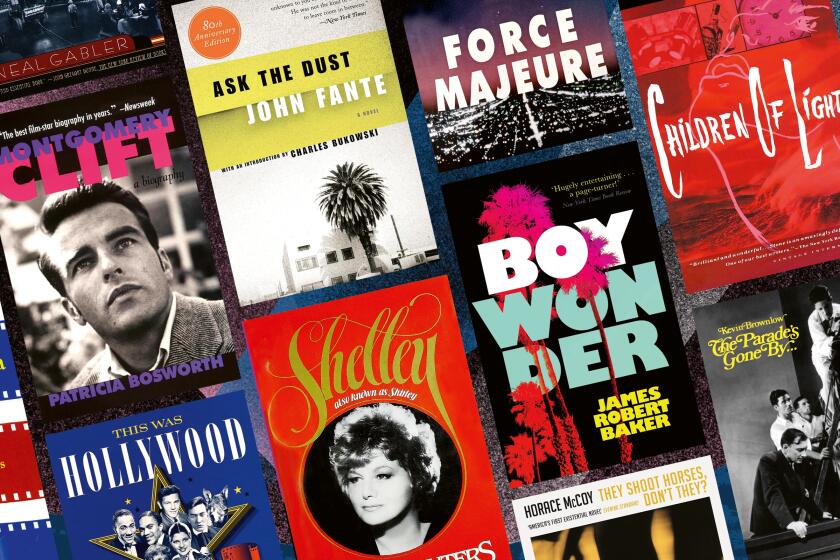

“Tiny: Streetwise Revisited,” an update of her 1988 monograph, was one of two books Mark completed just before her death. It is one of the most striking and moving of this season’s photography books, which includes a massive volume of Andy Warhol’s Polaroids and Catherine Opie’s anthropological look at Elizabeth Taylor’s belongings.

Over the years, Mark was frequently compared — a little too easily — to Diane Arbus, another fearless photographer drawn to the unfamous. But where Arbus was often merciless in her work, Mark showed empathy in pictures that mingled bluntness with grace.

When Life Magazine assigned Mark to photograph runaways and street kids in 1983, she ended up in Seattle, which, she wrote, had just been “voted America’s most livable city.” On Pike Street, teens were prostituting themselves and selling blood for cash. They slept under freeways and were dying from drugs, violence and exposure. They were, author John Irving writes in the introduction, “unloved, poor, unwanted, abused.”

The book is built round Tiny but begins as the story of an entire population of street kids. One adolescent girl is photographed on the sidewalk holding a rag doll close as she drags on a cigarette, a hard look on her young face.

Soon after that initial Life assignment, Mark’s husband, filmmaker Martin Bell, made an Oscar-nominated documentary about the homeless teens, “Streetwise,” as Mark continued to photograph, her focus ultimately turning to Tiny. By 1985, Tiny was pregnant with the first of 10 children by multiple fathers and in the early stages of a lifelong struggle with drugs.

There is sadness and disappointment to the pictures here but also brief moments of joy. The connection between the photographer and subject was meaningful from the beginning; in the closing notes, Mark reveals that in 1983 she offered to take Tiny with her to New York on the condition that she attend school. Tiny preferred to remain on Pike Street.

The other book the photographer completed just before her death was “Mary Ellen Mark on the Portrait and the Moment,” an essential text for examining a difficult world. She writes: “If your subjects have meant something to you, they live with you forever.”

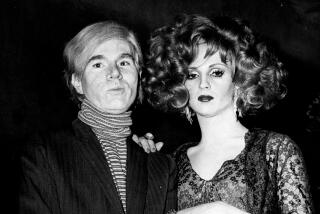

The work of Warhol inhabits an entirely different spectrum of experience. The acclaimed Pop artist was an obsessive photographer as well as a constant subject in front of the camera. In “Andy Warhol: Polaroids 1958-1987,” he points his instant, pre-Instagram camera at a daily parade of the famous and infamous: Divine, Sylvester Stallone, Jimmy Carter, Alfred Hitchcock, Candy Darling and more.

Many are just snapshots, but others capture something deeper about Warhol’s cultural moment, showing both gloss and grit in his celebrities. Some were later used for his famous silk-screen work. There are self-portraits of Warhol as a woman and still lifes of scattered knives, a spilled Coke can and more.

The earliest pictures are raw documents of his Factory life and the New York art world; by the early 1970s, Warhol had developed a distinctive style, with the Polaroid as a medium, creating a look of neon glamour and decadence that fit the time and place.

One of Warhol’s Polaroid subjects was screen legend Taylor, but his high-gloss approach couldn’t be further from the human-scale glamour captured by Opie in her book “700 Nimes Road.” The photographer, then known for provocative portraiture, landscapes and social commentary, never met the Hollywood actress, but she was given access to her home to create a different sort of portrait focused on her accumulated personal belongings.

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

Opie hoped to share what she photographed with Taylor, but the actress died before the project was finished. In part inspired by William Eggleston’s pictures of Graceland six years after Elvis Presley’s death, Opie dived into Taylor’s closets and jewelry cases, into her living room and kitchen and hallways. What she found was not a cartoon character from tabloid America but someone “deliciously regular,” as writer and critic Ingrid Sischy puts it in an afterward.

The photographs include a row of gleaming Academy Awards, a closet full of fashionable cowboy boots, purses and extremely precious jewelry in worn boxes. There is a sea of colorful fabrics from decades of gowns, and tabletops covered with framed pictures of loved ones past and present, of babies and famous friends, of husbands Mike Todd and Richard Burton, of the real life lived beyond the spotlight.

Fame requires the fuel of obsessiveness that only true fans can provide. No fanatics in all of pop culture are more intense than listeners of heavy metal, the subjects of Jacob Ehrbahn’s astonishing “Headbangers.”

The idea is simple: capturing portraits of metal fans at a peak moment of ear-rattling ecstasy, whipping their hair to their noise of choice. The faces frozen by the camera shutter reveal a range of extreme emotions, from brutal joy to stomping rage and something approaching nirvana.

The Danish photographer finds something of real beauty and excitement among this population too often dismissed as misfits and hard cases. Some of the faces are battered, others just young fans out for a good time. The feelings here are rabid and adoring, and reflect a depth of experience from one more corner of the unfamous.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.