J.C. Gabel’s indie press gamble, Hat & Beard

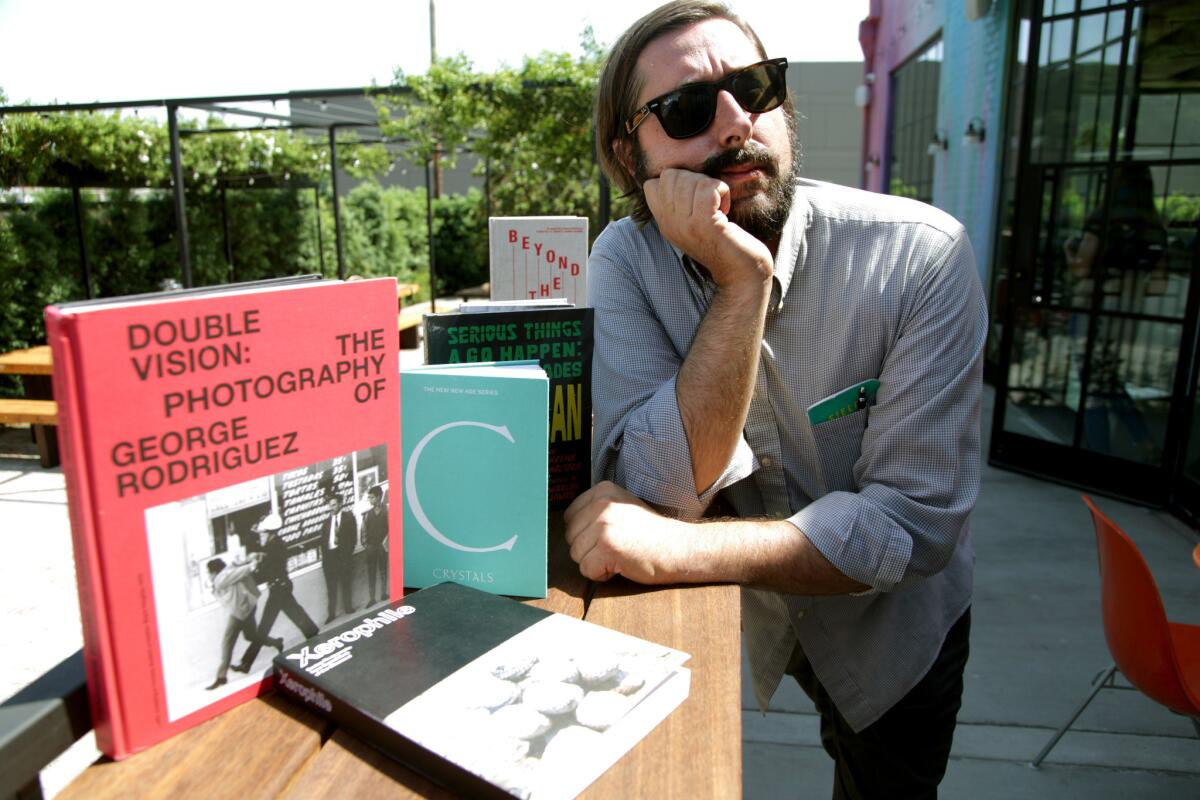

It’s hard to avoid noticing that J.C. Gabel, a tall, almost burly transplant from Chicago, is — among other things — a bit of a ranter. One August morning, as he sips his herb tea, he talks about how both Orwell’s and Huxley’s visions of dystopia have nearly been realized, describes his press’s former distributor (D.A.P.) as “Destroyer of All Profits,” calls at least one captain of industry a “dot-com sociopath” and dismisses much of Los Angeles culture as “trust-fund kids running fake businesses.”

But the difference between Gabel, 42, and most people who declaim loudly on the patios of bookstores is that a) he’s generally — or at least arguably — right most of the time and b) he’s managed to put his money where his mouth is. That is, he is not just a disgruntled crank but also a literary force of nature who’s pouring his considerable enthusiasm into — he hopes — reinventing the small press for the post-crash 21st century.

Gabel’s press, Hat & Beard, will double its print run this fall, putting out 10 art and photography books, including a photo-heavy volume about the chaotic 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago that reprints a classic Esquire story by Terry Southern. (Like many of his releases, it will be accompanied by a touring gallery show.) This month, Hat & Beard will launch a subscription plan that Gabel compares to the 7-inch singles that Sub Pop put out in the 1990s. And although a deal just fell through to open a store based on Stanley Rose Bookshop, a center of ’30s Hollywood culture, Gabel continues to search for a place that can serve as a gallery, store and cultural space.

Surviving in the current publishing climate is impressive; thriving and expanding is almost bizarre. And Gabel and company have done it, in large part, while scorning some of the field’s standard business practices, including the dominant force in publishing today — Amazon.

Gabel developed his rebel spirit and literary intensity while growing up in and around Chicago at a time when the city was becoming a major hub for independent music and the infrastructure that supported it. Gabel often searches for metaphors to describe his company; he likens it to “a print collective,” a farm-to-table restaurant and to “a production company that has its own imprint.” But the closest parallel may be to the artist-friendly, punk-inspired indie-rock labels — Touch and Go, Drag City, Merge — he once worked for. He likens his books, which are handsomely produced and sometime include soundtracks or small-run posters, to music box sets, which consumers buy in part for the packaging and their status, even in these de-materialized times, as objects.

While still in college, in the mid-’90s, Gabel began putting out Stop Smiling, billed on its cover as the Magazine for High-Minded Lowlifes. Here, his retro-obsession started to show itself: Rejecting the move toward celebrity and shallow listicles, Gabel tried to emulate the magazines from right before he was born, with the old Esquire, Playboy and Rolling Stone as models, along with a touch of the British rock and lad magazines of the ’90s.

In 2012, Gabel and his wife moved to Los Angeles, in large part because he’d landed editing work for Hollywood-based Taschen, as well as Chronicle and Phaidon. (When his wife, Sybil Perez, who now copy edits many of the books, became pregnant, it became harder to move back.)

Four years later, he co-founded Hat & Beard with designer Brian Roettinger, a move he compares to getting the old band back together, also relying on writer Jessica Hundley and the former Stop Smiling crew. The press’ name comes from a song by avant-garde horn player Eric Dolphy, a Los Angeles native, about Thelonious Monk’s eccentric style. (“It’s sort of willfully obscure,” Gabel says, noting the phrase’s oblique connection to L.A.) Two years ago, he threw a 40th birthday party, and he recalls friends coming up to him with, “Dude, you’re 40, and you’ve gone back to selling art books out of the trunk of your car.”

“He’s a very ambitious guy,” says Jim Heimann, the Taschen editor who helped bring Gabel to the press. “He’s got a million ideas he’s always pushing here and pushing there. He keeps things moving, sometimes at breakneck speed. Sometimes the ideas work, sometimes they don’t. He’s always swimming.”

Hat & Beard is driven in part by what Gabel, its editorial director and publisher, calls “a nostalgia for the period before the internet changed everything — for the worst. The reason I moved into books is that I saw the physical medium surviving longer.”

The press’ output is unified by a crisp design that is a bit less luxurious than Taschen’s or Phaidon’s, an obsession with the pop culture and subculture of the past, and an interest in Los Angeles. But it’s eclectic and hard to predict. Hat & Beard’s four bestsellers so far have been a collection of hand-painted dance hall signs from Jamaica; an assembly of cactus photography; “Beyond the Beyond,” on the music of David Lynch’s films; and a tribute to the L.A. punk magazine Slash that involved more than a month of events in Los Angeles, New York and London.

Two other recent books show what Hat & Beard does in a way few others can: “Double Vision,” which collects the photography of George Rodriguez, who documented the Chicano movement as well as the bands of the Sunset Strip, and “Listen to the Echoes,” a series of interviews, alongside rare photographs, with Ray Bradbury. (The book’s editor, Sam Weller, calls Gabel a “visionary madman and manic impresario” in the acknowledgments.)

That these books are out at all defines Hat & Beard’s unusual stance: Besides the taste involved, most of them would be considered too niche-oriented for large presses, and it’s difficult for a publisher any smaller to do convincing art books, which require expensive paper and printing.

So at least as important as Hat & Beard’s retro-rebel sensibility is its business approach. By keeping a lean organization — with just two full-time employees, one in charge of production, another of sales and marketing — and selling many of the books at bookstore events and gallery openings, the press can break even on even small print runs. To make it all go, Gabel, who has two young children, works what he describes as 80 to 100 hours a week, but is not a full-time staffer.

Gabel is especially excited by his subscription series, the First Editions Club, by which Hat & Beard purists will receive a new book every two months; he hopes to enlist 2,500 subscribers over the next few years. “This way,” he says by email, “we don’t have to live and die by a rigged wholesale system to sell books.”

Gabel’ general complaint about distribution-as-usual is that because art books are expensive to produce, the huge cut taken by middlemen leaves a press with just two options: one, charge a small fortune for each book, or two, earn so little on each volume that writers, photographers and graphic artists make almost nothing. So he’s seeking a third way.

The future of the new, more ambitious Hat & Beard may rest — as unromantic as this might sound — not with Gabel’s fighting spirit but with the issue of distribution. It’s an arrangement that can make or break a publisher, determining not just where its books do and don’t land, but how much money the press makes on each one.

Gabel was so frustrated with his deal with DAP that he broke their contract, leading to significant fines and a year of self-distribution. He’s on the verge of a new deal he can’t speak about yet and whose details remain to be determined. But one thing that’s likely is that he will continue his resistance to Amazon, a company that many publishers and authors resent but generally grit their teeth and live with. His stand could make him a hero to the revenge-of-analog crowd; it could also prove to be Gabel’s Folly.

“I totally understand why he’d want to do it,” says Heimann. “The whole publishing industry since 2008 has had to rethink everything it does, with the decline of retail outlets. Amazon is basically holding everybody hostage, holding a gun to your head saying, ‘Here’s our deal.’” But bypassing Amazon, he says, “limits your press runs. That’s a hell of a lot of energy to put out to keep the machine running.” Gabel, who calls himself and his bandmates “cultural warriors,” is spoiling for a fight, and he’s nothing if not energetic.

Gabel may lose this battle. But if he can make the evolving Hat & Beard work as well as the first, smaller incarnation of his teenage dreams, he could chart one way forward. “The endgame for me,” he says, “is, can you make this stuff profitable again in 2018, when all the statistics and all the metadata tells you otherwise? For the love of making things.”

Timberg is a writer and editor who lives in Los Angeles and is the author of “Culture Crash: The Killing of the Creative Class.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.