Boeing faces growing pressure over crash as foreign airlines ground the 737 Max

Boeing Co. came under growing international pressure to account for the second crash of its 737 Max aircraft, as China and other countries grounded their fleets and investors pounded the aerospace company’s shares in trading Monday.

Investigators found the black boxes of the Ethiopian Airlines jetliner that crashed Sunday shortly after takeoff, killing 157 people. The data have yet to be downloaded, and information about the cause of the accident remained limited.

But aviation experts pointed to similarities with the October crash of a Lion Air 737 Max not long after it took off from Jakarta, Indonesia. A preliminary investigation said the accident was related to a software modification in the new jetliner that erroneously caused the aircraft to enter a series of dives.

The Federal Aviation Administration on Monday issued a statement of confidence in the safety of the 737 Max, saying it would “take immediate and appropriate action” based on further information but “to date we have not been provided data to draw any conclusions or take any actions.”

Boeing announced late Monday it would update software in the planes’ flight control system in coming weeks.

Several U.S. airlines, facing calls and emails from nervous passengers, expressed support for the aircraft.

Southwest Airlines, the largest domestic carrier and biggest operator of the 737 Max, with 34 planes and an additional 219 on order, said: “We remain confident in the safety and airworthiness of our entire fleet of more than 750 Boeing 737 aircraft, and we don’t have any changes planned to 737 Max operations. We are fielding some questions from customers asking if their flight will be operated by the Boeing 737 Max 8.”

But authorities and airlines in China, Indonesia, Ethiopia and elsewhere moved swiftly to ground their fleets of the 737 Max 8, Boeing’s most successful and newest model, and one of its biggest profit generators.

The risks facing Boeing were clear Monday when its shares plummeted as much as 13% in early New York trading. They closed down $22.53, or 5.3%, to $400.01 in heavy trading.

“Because this is a new model and there are similarities with the two accidents, Boeing should put safety first and ground this aircraft,” Jim Hall, former chairman of the National Transportation Safety Board, said in an interview. “After Lion Air, Boeing was going to provide a fix to the system which has not been done yet.”

In a statement, Boeing said, “We are taking every measure to fully understand all aspects of this accident, working closely with the investigating team and all regulatory authorities involved. The investigation is in its early stages, but at this point, based on the information available, we do not have any basis to issue new guidance to operators.”

If a defect was responsible for both of the accidents, it would represent a potentially grave threat to Boeing’s most important product. As of January, the manufacturer had more than 4,700 orders from around the world for the fuel-efficient, twin-engine jetliner. Boeing is among the nation’s top industrial exporters, responsible for the bulk of $121 billion in annual commercial aircraft exports.

“Boeing is in trouble,” said Robert Ditchey, an expert witness in air safety matters, an aeronautics engineer and a former airline executive. “This is like a nuclear war for them. They are going to try to get the answer to this as quickly as possible.”

Half a dozen safety experts interviewed by The Times cautioned that almost no cause of the Ethiopian Airline accident could be ruled out, including aircraft system defects, pilot error, terrorism or even pilot suicide.

But more questions will be raised than answered until investigators can at least download information from the jetliner’s event data recorder and cockpit voice recorder that were found at the crash site, southwest of Addis Ababa, the nation’s capital.

The remains of the aircraft were in bits and pieces in a confined area, suggesting that it struck the ground nose first at a sharp angle, Ditchey said.

The airport at Addis Ababa is at 7,200 feet elevation. The 737 never reached more than about 2,000 feet above ground before it crashed eight minutes after takeoff, a duration that normally would take the aircraft close to its cruising altitude of more than 30,000 feet. Flightradar24, a website that tracks aircraft flights, reported that during its first three minutes the plane experienced repeated inflections of its vertical speed and at one point dropped about 400 feet.

“It wasn’t even close to a normal climb pattern,” Ditchey said.

The other unusual clue from Flightradar24 was data that showed the aircraft was traveling at nearly 400 knots, well above the allowable speed in the U.S. for aircraft below altitude of 10,000 feet. Experts said that such a speed could probably not be justified under any scenario.

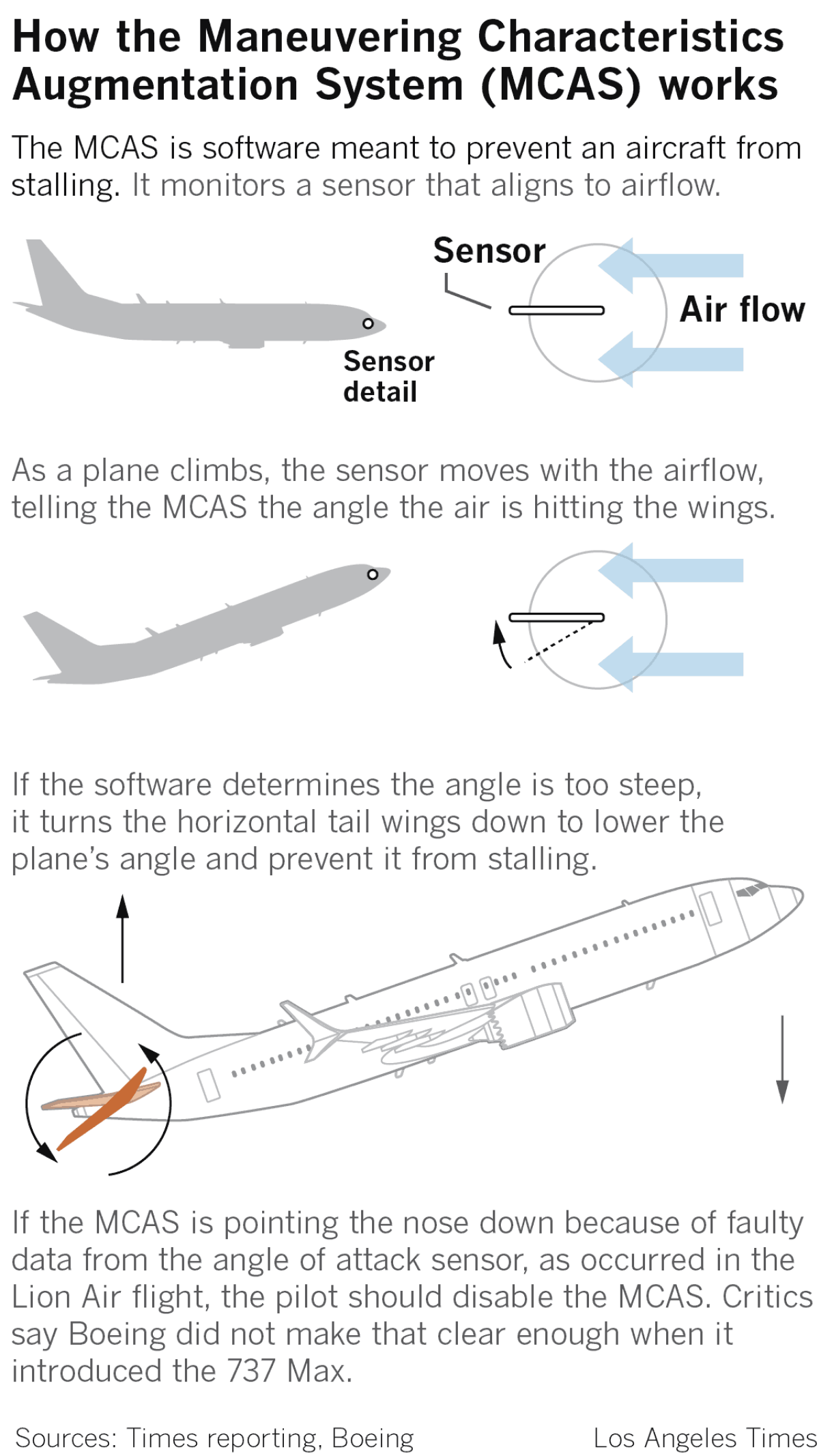

The Lion Air jetliner crash probably involved multiple causes, including glaring maintenance errors, pilot mistakes and training deficiencies. The plane was sent into about a dozen downward movements by a software feature in its flight control system — which goes by the name of Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, or MCAS — that relied on erroneous data from a sensor that measured its angle of attack, the angle at which air flows over the wing.

The MCAS software was put on the 737 Max to counteract the potential for the plane to pitch up at slow speeds and lose lift. The pilots could’ve switched off the software, which was done by a crew the previous day when it experienced the same issue.

The tendency for the nose to pitch up at slow speeds after takeoff was created when Boeing moved the engines closer to the fuselage in redesigning the 737, which dates from the mid-1960s.

“Boeing has to sit down and ask itself how long they can keep updating this airplane,” said Douglas Moss, an instructor at USC’s Viterbi Aviation Safety and Security Program, a former United Airlines captain, an attorney and a former Air Force test pilot. “We are getting to the point where legacy features are such a drag on the airplane that we have to go to a clean-sheet airplane.”

Richard Aboulafia, an aerospace analyst and vice president at Teal Group, said that he hears such suggestions from people all the time. “It is not clear that a new technology design would have paid off with a single-aisle jet.”

Although Boeing is taking a “reputational hit” with the accident, he cautioned that the Ethiopian accident could turn out to be a case of pilot error or terrorism. “If it has nothing to do with the airplane system, then it has nothing on Boeing,” he said. “A lot is at stake. We will know more.”

Nonetheless, U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) called on the FAA to ground the 737 Max “until the cause of the crash is known and it’s clear that similar risks aren’t present in the domestic fleet.”

Paul Hudson, president of the passenger rights group FlyersRights.org, echoed Feinstein’s call, saying, “The FAA’s ‘wait and see’ attitude risks lives as well as the safety reputation of the U.S. aviation industry.”

Hall, the former NTSB chairman, said his recommendation for a grounding is based in part on what he learned during his first accident investigation, involving a 737 jetliner that crashed near Pittsburgh in 1994.

Hall led that investigation, which became the longest in NTSB history when it went on for five years. Boeing insisted, Hall said, that the accident was caused by pilot error. But the investigation ultimately found that a defect in the hydraulic system caused the rudder to reverse direction.

“When you pressed the rudder pedal one way, the plane would go the other way,” he recalled. “My concern in that experience with Boeing on the 737 in the 1990s is transparency. They failed to be transparent. I would think from a business standpoint, the prudent thing to do is ground the airplane.”

In 2013, the FAA ordered airlines to cease operations of Boeing’s then-new 787 Dreamliner after five incidents in five days of fire originating in the plane’s lithium ion battery. None of the planes crashed and Boeing implemented a fix for the battery overheating problem. Before that, the FAA had last grounded a U.S.-built aircraft in 1979, when it ordered a halt to flights of the McDonnell Douglas DC-10.

When Boeing introduced the newest version of its 737 a few years ago, U.S. carriers were enthusiastic about its promise of fuel efficiency — Boeing boasts it has 10% better fuel mileage than the next most economical single-aisle jetliner — and its quiet interior. The 737 Max, assembled in Renton, Wash., became Boeing’s fastest-selling plane.

Besides Southwest in the U.S., American Airlines has 24 737 Max jetliners in its fleet, with an additional 90 on order over the next two years. United Airlines has 14 of the models in service and orders for 100 more.

On Monday, those U.S. carriers also voiced confidence in the jetliners. “We have made clear that the Boeing 737 Max aircraft is safe and that our pilots are properly trained to fly the Max aircraft safely,” United Airlines said in a statement.

American Airlines issued a similar statement: “We have full confidence in the aircraft and our crew members, who are the best and most experienced in the industry.”

Airlines said they have not yet seen a significant push by passengers to cancel or rebook flights.

At Los Angeles International Airport on Monday, co-workers Jenny Garcia and Christina Perez flew in from Houston on Southwest Airlines. Perez said she wasn’t concerned because the airline has been reliable in the past. “Maybe if I was on an international flight,” she said.

Garcia said she was aware of the crash but also didn’t feel concerned.

“The chances of that happening are so slim,” she said.

The world’s airlines recorded the safest year on record in 2017, with just 1.1 accident for every 1 million flights, according to the International Air Transport Assn., a trade group for the world’s air carriers. In 2018 the accident rate rose to 1.35 accidents for every 1 million flights, or one accident for every 740,000 flights.

Times staff writers Melissa Gomez and Alexa Diaz contributed to this report.