Silicon Valley is not ready for 2020. Just read the Mueller report

Reading Robert Mueller’s report, it’s hard not to feel like that frog who gets slowly boiled alive. Many of its most incendiary allegations had already been published elsewhere. We knew most of it, but now, we really know.

Donald Trump really did order the White House counsel to have Mueller fired. Trump really was working on a Trump Tower Moscow project through at least June 2016. A Russian lawyer really met with campaign officials, including Jared Kushner and Donald Trump Jr., after promising an intermediary to deliver “official documents and information that would incriminate Hillary.

Others will weigh in on what it all means for the Trump presidency. As a technology reporter reading the report, I realized that I was partially submerged in another pot of boiling water. Several pages of the findings remind us that U.S. social media companies played an essential role in the Russian interference operation during the 2016 election.

Mueller’s report is unambiguous about that fact. On Page 4, it says, “The Internet Research Agency (IRA) carried out the earliest Russian interference operations identified by the investigation — a social media campaign designed to provoke and amplify political and social discord in the United States.”

The report says that interference began in 2014 and then evolved into an effort to support then-candidate Trump by early 2016. Facebook Inc. said that as many as 126 million people may have been touched by IRA. And Twitter Inc. alerted 1.4 million people that it believed had interacted with an IRA account, the report says. Facebook is mentioned 81 times. Twitter gets 71 mentions.

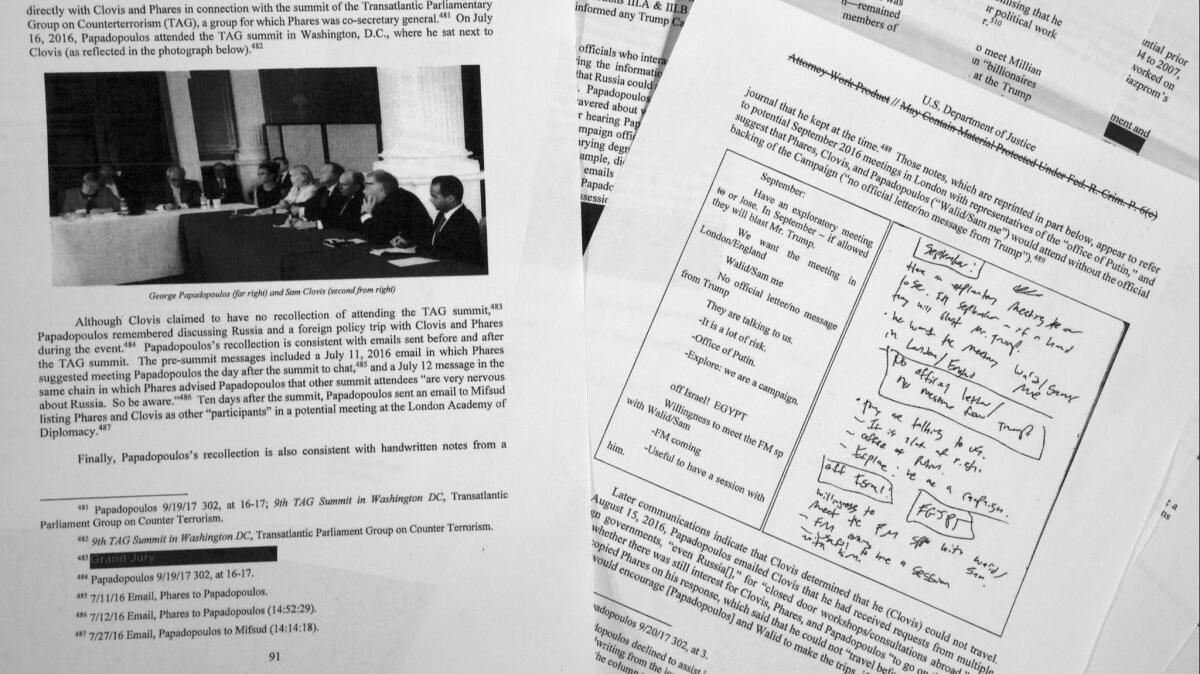

Kudos to Google which only gets six mentions — mostly in the context of Trump administration officials naively googling people. For example: “After receiving [Geroge] Papadopoulos’s name from [campaign official Joy] Lutes, [campaign co-chairman Sam] Clovis performed a Google search on Papadopoulos, learned that he had worked at the Hudson Institute, and believed that he had credibility on energy issues.” Very thorough.

In all seriousness, the broader findings raise a question that’s every bit as serious as the search for proof of collusion: Are U.S. social media companies prepared for the next election?

Facebook and Twitter have so far focused their preparation efforts on banning accounts, and deleting groups controlled by Russian agents. But that seems to be sort of a whack-a-mole approach, knocking out bad actors only after they’ve made an impact. This seems like a time when we should be asking more fundamental questions about how Facebook and Twitter operate. And one central issue is that online, people often aren’t who they say they are — and as a result, act with impunity.

In some ways, that’s liberating. Anonymity allows people who might otherwise be repressed or fearful to express their ideas. It’s one of the wonders of the internet. But it also enables people, Russian or not, to act in all sorts of disingenuous ways.

As a reporter interacting with trolls online, it can be frustrating to face accounts without any discernible identity. For instance, I’d love to know whether people who Tweet on $TSLA and $TSLAQ are long or short the electric car company — and whether they’re earnest observers or users spinning their own mini-propaganda machines for their respective bets.

While that’s a silly example, there are far more terrifying ones. Countries such as Venezuela, Iran and Bangladesh have all tried their hands at their own social media disinformation campaigns. And neo-Nazis have taken to impersonating Jews and other minorities online.

The push and pull over online identity comes back to the central question of free speech online. But the alternative to anonymity isn’t necessarily some central government-accessible database like we’re seeing in China. It’s possible to imagine, for example, a sort of scaled-up version of verified Tweets. Social media companies could give people who prove that they run their Twitter account a bigger audience or more power to appear in replies. Twitter could even reward people who don’t publish their name publicly, but are willing to prove that they live in the country they say they do.

This isn’t a fully baked plan, of course, and there are plenty of trade-offs to be weighed. But the Mueller report should be a reminder that the status quo is not working, and probably won’t be before votes are cast in 2020. After all these years, one central tenet of the internet has held true, proving far more insidious than it once appeared: “On the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.”

Maybe they should.

Newcomer writes a column for Bloomberg