In downtown L.A., sealed-off hotel rooms offer peek into the past

Real estate developer Nick Hadim made a risky climb through an upstairs window of an abandoned building to see what he and his investors had gotten themselves into.

Downtown’s Alexandria Hotel had long been rumored to be haunted. But instead of ghosts, he found a time capsule.

There, in a sealed-off wing of the otherwise bustling complex, he encountered a dusty suite deserted in some haste in the 1930s. A crumbling bowler hat lay next to a torn armchair. An antique typewriter sat ready for use on the side of a wooden desk. In the bathroom was a cast-iron claw-foot tub last filled with water during the Great Depression.

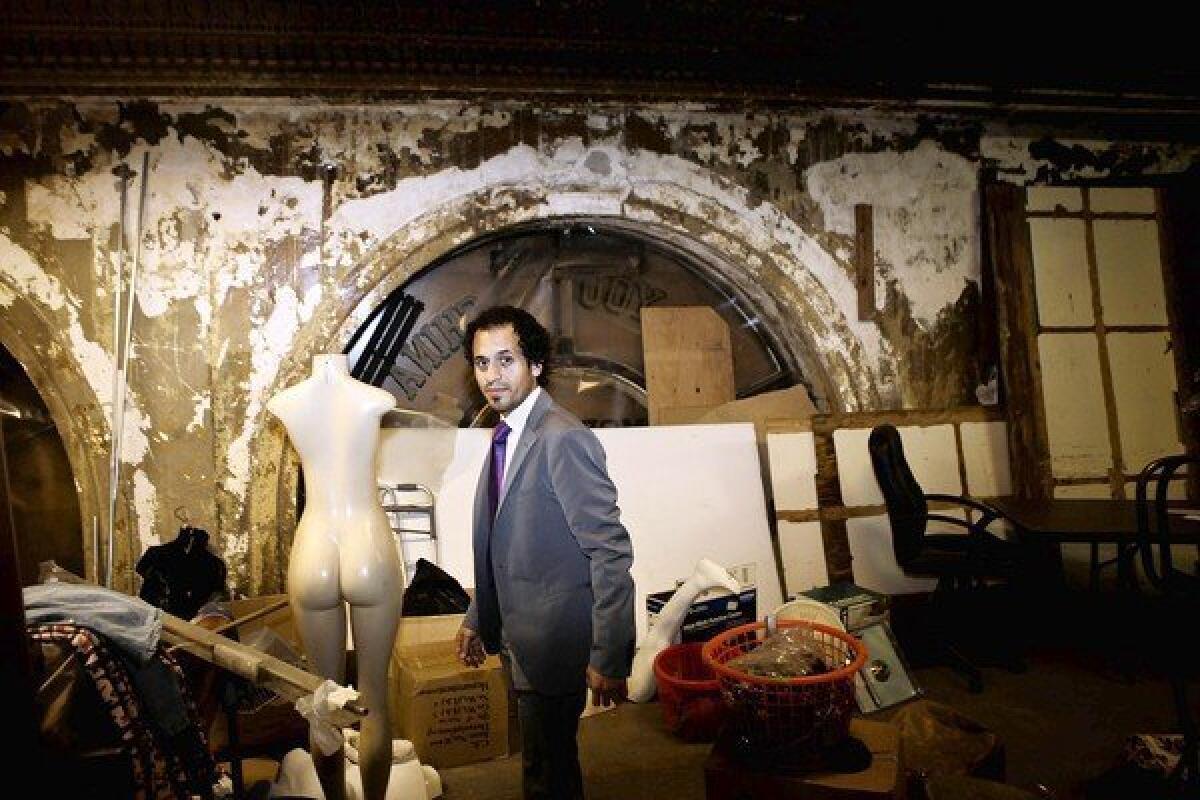

“It’s freaky,” said Hadim, a Culver City entrepreneur with experience renovating old downtown buildings. Hadim plans to spend $3 million turning the Alexandria’s abandoned wing into small apartments, which he hopes to rent at premium rates in what he will call the Chelsea Building.

What his investors bought were century-old deluxe hotel rooms once part of the Alexandria, a stalwart presence at 5th and Spring streets since the early 1900s, now a low-priced apartment complex. Hadim’s group purchased just a small slice of the old hotel building, a wing that was sealed shut on all seven floors in a fit of pique in 1938 and has been seen by few eyes since then, except those of wandering birds and the occasional vandal.

What most of the 35 rooms hold is a mystery, because the corridors lack an entrance other than the hallways of the Alexandria — which have been walled off for nearly 75 years.

The lowest of the building’s six hotel room floors can be accessed from an adjacent roof and has been stripped by scavengers. Still, its tall, wide windows, high ceilings and dark wood floors retain their grandeur even as pigeons flit in and out of the broken windows.

The abandoned rooms were part of what was widely considered the city’s premier inn of the early 20th century, according to Los Angeles Times archives. Young aristocrat Winston Churchill stayed at the showplace, as did opera star Enrico Caruso and Presidents Taft, Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt.

But the city moved on. The 500-room Alexandria was eclipsed in status by the elegant Los Angeles Biltmore Hotel in 1923.

The wing became unreachable because the hotel’s owner sealed the halls leading to it with bricks and mortar as a punishment, said Lee Roddie, daughter of the wing’s builder. Roddie explained her family’s tale of woe to The Times in 1967, when the elderly woman was still paying property taxes on her mostly inaccessible building.

As the Alexandria was being built in 1905, Roddie’s father, William Chick, tore down his livery stable next door at 218 W. 5th St. and went into business with the hotel’s developers. Chick constructed an addition to the hotel on his property that was a seamless extension of the Alexandria, fully accessible from the hotel’s corridors.

Stairs or an elevator were an unnecessary expense, he reasoned, and would have eliminated some money-making guest rooms.

“Father made a terrible mistake,” Roddie said, looking back on that decision.

The hammer fell in the Depression. Hard times forced the Alexandria to close in 1934. Three years later, movie producer Phil Goldstone bought the hotel and reopened it in 1938, to the delight of Roddie, who was by then sole owner of the wing. But their relationship quickly soured.

“One of the tenants in the main part of the hotel moved into one of the two stores on the bottom floor of my wing because Mr. Goldstone raised his rent,” Roddie told The Times.

“It made Mr. Goldstone mad. He said he didn’t need my wing. He sealed off the corridors to my rooms on each floor, making access impossible. It’s been that way ever since.”

Tall tales used to circulate about the “haunted hotel,” she said. One of the most common was that the owner’s husband was killed on the Titanic and the widow kept it closed in his memory.

“My husband died of flu during World War I,” Roddie said.

Roddie and subsequent owners were able to rent out only the building’s ground-floor retail space, which has a narrow concrete stairway in back leading to a sealed-off portion of the Alexandria’s former mezzanine. Now used for storage, the once-grand mezzanine still has elaborate, gilded crown molding and rounded windows adorned with advertising in gold leaf.

A tall wooden ladder leads to a hatch in the roof. From there, the lowest level of the building’s long-lost hotel can be entered through one room’s window.

A short hallway bisects the floor, and the transom windows of some rooms remain open, as they would have been in the days before air conditioning. The decayed wallpaper looks like peeling paint. The hardwood floors are speckled with pigeon guano but remain firm and may be restored with simple sanding, Hadim said.

Outside on 5th Street, Hadim will wash the grimy brick walls and scrub the twin griffins guarding the Beaux Arts-style building. For many decades each griffin held in its mouth a chain with an illuminated globe, a detail Hadim may bring back.

In the decades after World War II, the Alexandria’s prime neighborhood at 5th and Spring gradually fell into decline. So did the hotel. In 1988, city officials called the Alexandria the worst drug-trafficking spot in Los Angeles.

Now the city’s historic downtown-turned-skid row is reviving, with new restaurants, bars, shops and thousands of affluent residents living in converted office and industrial buildings. The Alexandria Hotel-turned-apartment complex, which has separate owners not part of the Hadim group, has also come up in the world.

Hadim figures that by eliminating the utility closets on each floor and a total of seven guest rooms, he can create enough space for an elevator and stairs. He’ll work from the original plans by John Parkinson, a famed Los Angeles architect whose later projects included City Hall and Union Station.

Hadim hopes to start work on the Chelsea by January and finish in the winter of 2013. He plans to rent the street retail spaces to a cafe and perhaps a clothing boutique. The building’s deep two-story basement might be turned into a nightclub or lounge.

Across 5th Street, another developer recently finished converting the 1923 vintage Chester Williams Building from offices into apartments. A Walgreens drugstore will rent the ground floor of the 12-story building. The first Starbucks in the historic district recently opened about a block away.

“A lot is happening,” Hadim said. “In five years, it’s going to feel like Manhattan around here.”