Palmdale boy’s death prompts changes at child welfare agency. But questions remain

Los Angeles County’s child welfare agency shed more light this week on the case of a 4-year-old boy from Palmdale who died after he was returned to his parents’ home following reports of abuse. But the information has raised more questions about why social workers didn’t act on a May court order authorizing his removal.

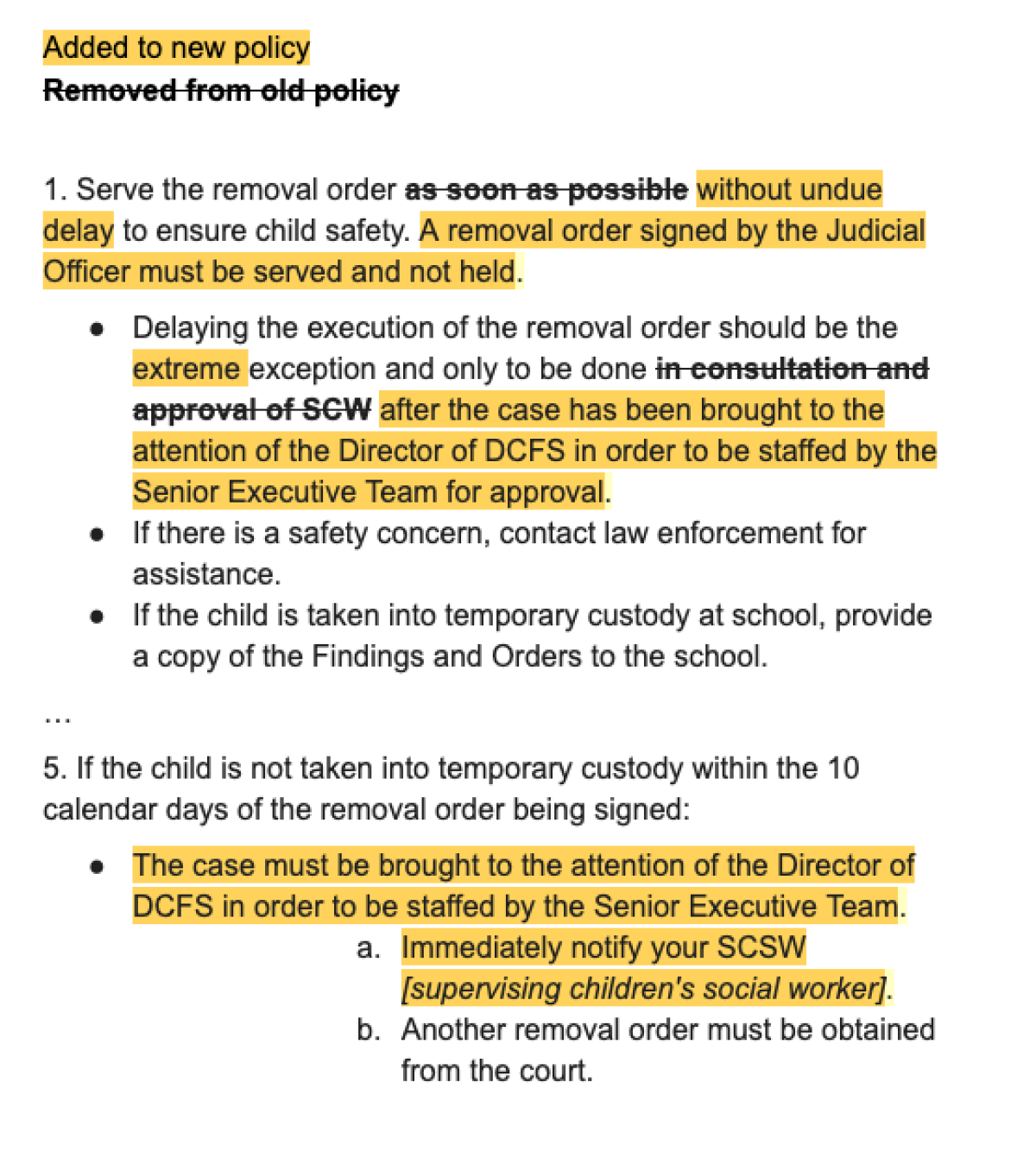

In a disclosure to The Times, the Department of Children and Family Services said it recently changed policy on so-called removal orders, requiring social workers to notify the agency’s director — not just a supervisor — about cases in which a court order hasn’t been executed. One such case was that of Noah Cuatro, who died this month under what authorities say are suspicious circumstances.

Last year, DCFS received court orders authorizing the removal of 8,900 children. It declined to follow through only seven times, according to data released by the department to The Times, an indication that what happened to Noah is extremely rare.

At the time of his death, Noah was under active supervision by the child welfare agency, and his parents had been under investigation, after at least a dozen calls were made to authorities alleging abuse in the home, The Times has reported. Noah previously had been removed and put in foster care, but had been reunited with his parents, Jose and Ursula Cuatro. Neither could be reached for comment.

Noah’s parents called 911 on July 5 saying the boy had drowned — a claim later questioned by Sheriff Alex Villanueva, telling reporters his body had signs of trauma that were not consistent with drowning.

In recent days, the Sheriff’s Department, and district attorney and medical examiner-coroner’s offices, have released few details about the case, which is still under investigation as a suspicious death.

Investigators asked that the autopsy records be withheld from the public and they’ve asked DCFS not to comment about some aspects of the case, authorities say.

Citing family privacy laws, the child welfare agency also has declined to discuss why it didn’t execute the removal order. That order remains sealed by the court, as does a 26-page motion by a DCFS social worker seeking the order.

The Times this week petitioned Los Angeles County Superior Court and Commissioner Steven E. Ipson for access to Noah’s case file, but there has been no response.

The policy change at the child welfare agency does offer some clues.

The new policy makes clear that DCFS Director Bobby Cagle, not social workers, will be accountable for removal orders, raising the question of whether a mid-level official authorized the department to stand down on the order involving Noah.

The policy also requires the director to be notified in cases in which a court order hasn’t been executed within 10 days.

“The department recently updated its policy with regards to removal warrants to ensure that social workers and their supervisors engage with senior leadership to help guide their case practice and strengthen child safety,” Cagle said in a statement.

Experts say the changes could help ensure more accountability in such cases.

“I thought it was a great step,” said Michael Nash, a former presiding judge of Los Angeles County’s Juvenile Court who now leads the Office of Child Protection for the Board of Supervisors. “You want to have a more clarified line of authority when these things come up.”

The updated policy comes amid heightened scrutiny of the department’s operations in the sparsely populated Antelope Valley, where the DCFS maintains offices in Lancaster and Palmdale and has struggled to recruit and retain social workers.

The news about Noah’s death has left staff there “devastated,” said Cagle, who visited last week. “There was a palpable sadness amongst everyone that I met.”

The department’s operations in northern Los Angeles County have long been an issue.

The average length of service for a DCFS social worker overall is about six years. But for Lancaster it is about five years, and for Palmdale the average is about four years, according to a report by Nash’s office.

Nash’s office gathered that data while investigating the death of Anthony Avalos, a 10-year-old Lancaster boy whose parents are awaiting trial for his death.

Anthony’s is one of a string of high-profile child deaths in the Antelope Valley in the last several years linked to child abuse investigations by the agency. Another is that of 8-year-old Gabriel Fernandez, who was killed in 2013 by his mother and her boyfriend after social workers mishandled evidence of escalating abuse and failed to file timely reports.

Both boys died a short drive from Noah’s home.

“The department has allowed children to remain in unsafe and abusive situations for months longer than necessary because it did not start or complete investigations within required time frames,” a state auditor concluded in May.

The string of deaths has led to criticism of the agency, which has hired thousands of new social workers in recent years in an effort to improve the supervision of children in need.

The department also has struggled to maintain ideal ratios of managers to social workers, leading to concerns by policymakers about the ability to offer a high standard of care. Managers are crucial for training and mentoring new social workers, and for holding them accountable for deadlines in filing case assessments.

Cagle said his office has improved.

The county Board of Supervisors — led by Kathryn Barger, who represents the region — has pushed DCFS not to lose focus on its challenges in the Antelope Valley once the attention from Noah’s case fades.

On Tuesday, the board called Cagle to testify about a motion authored by Barger that would compel a more comprehensive and sustainable staffing plan for the region.

Ideas include working with local colleges on recruitment, and to improve hiring and retention with financial incentives such as location bonuses, additional pay and tuition forgiveness. The supervisors also directed the department to dedicate a deputy director to the region.

“I’ve followed through with a sense of urgency myself and immediately began working with my staff to address the needs in the Antelope Valley, and to also better understand the challenges from the perspective of the workers that are involved,” Cagle said.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.