From the Archives: Oscar Bayer, 1925 shootout hero

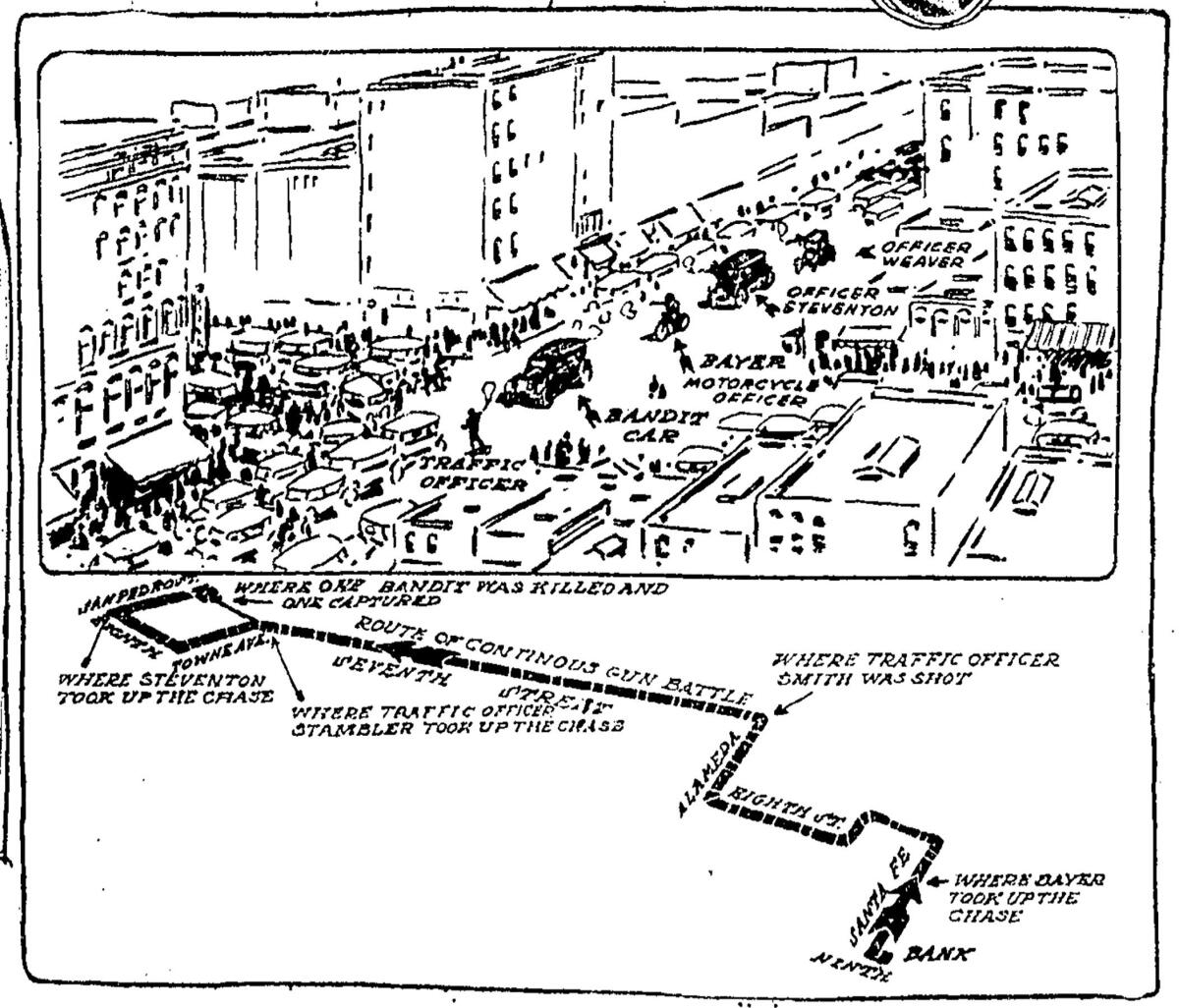

At 10 a.m. on Aug. 22, 1925, Los Angeles police motorcycle Officer Oscar Bayer was peacefully watching traffic at 8th Street and Santa Fe Avenue. At that moment, one block away at 9th Street and Santa Fe, gunmen robbed the Hellman Bank.

Soon, a racing motorcar with four men inside drew Bayer’s attention. The next morning’s Los Angeles Times picks up the story:

...Thundering after it came another machine and the young officer heard a shout of “Hold-up–stop them.”

In the next few minutes, the officer wrote a page of police history of which the department will be eternally proud. As the shout reached him, the officer sprang on his machine and raced after the gunmen. Their response was a salvo of two sawed-off shotguns and four revolvers.

“I heard the bullets whizz by my head but I just gave my motorcycle the gun. I was mad clean through and wasn’t doing much thinking. I knew I wanted those birds, though.

“They turned north on Alameda to Seventh Street and west on Seventh to Central. They were firing as fast as they could pull triggers. Then a bullet struck me in the right breast. I didn’t know at the time how badly I was hit. It almost jarred me from my seat.

“So I shook my head as hard as I could to clear it and kept on. Another bullet tore through my sleeve and a third seared me below the hip. It stung terribly but all I could remember was getting madder. I reloaded my own gun on the fly. It was some job, but somehow I made it. I guess my rabbit’s foot was working overtime.

“They stopped at Seventh and San Pedro and three got out. Each carried two guns. Two of them came toward me, firing as they ran. I let one have it. He spun around and fell. Only one bullet remained in my gun. I dodged behind another machine and let the second man have it. It crashed through his arm.

“Then I told him I would kill him if he didn’t surrender, though my gun was empty. That rabbit’s foot certainly did work. He took me at my word and surrendered.”

That was his story in brief. It was supplemented considerably by his fellow officers.

Bayer has been on the police force since 1921. He was made a motorcycle officer in 1923. He saw action while in the service for two years and eight months overseas with the Navy but admitted that in his adventurous life his greatest adventure came to him yesterday. He has a wife and two small children. After his discharge he took up aviation and is now rated as one of the Southland’s crack flyers.

::

This group shot was taken the afternoon of the shootout. When the photo appeared in next day’s Los Angeles Times, Charles Meyers was painted out of the picture by a staff artist. The reason is unknown.

Four suspects had robbed the Hellman Bank in downtown Los Angeles. In the ensuing chase and gun battle, suspect Rudolph Franta died and Anthony Kasper was wounded and captured. Two other suspects, Charles Schultz and Rudolph’s brother Ed Franta escaped but were later caught.

Traffic officer Wylie. E. Smith, who joined in the shootout at 7th and San Pedro, was killed. Bayer and Smith received the Los Angeles Police Department’s Medal of Valor.

Bayer, now a local hero, recovered from his wounds and returned to duty. An Aug. 26, 1925, Los Angeles Times article reported that at a Hollywood party, “Oscar Bayer, police hero of the bandit bank battle, [will] make his appearance” riding “his bullet-riddled motorcycle.”

By 1929, Bayer rose to the rank of detective lieutenant.

In addition to his LAPD career, Bayer also was an Army Air Force Reserve pilot. He served with the 478th Pursuit Squadron, based at Clover Field, Santa Monica. During the late 1920s, several Los Angeles Times articles reported on Bayer’s aviation exploits.

On April 16, 1929, Bayer died in an airplane crash at the municipal golf course next to Clover Field. He left behind his wife and four children.

Because he died while off duty, Bayer’s widow and family could not receive his police pension. On April 19, 1929, the Los Angeles Times reported:

The young policeman -- he was only 31 years of age -- fell to his death at a time when he was not in line of duty, thereby excluding the family he leaves from the lifetime monthly allowance that otherwise would have insured their maintenance.

With the welfare of Mrs. Bayer and her children in mind, friends of the dead officer met yesterday to discuss ways and means of assisting the widow to surmount the situation that confronts her. They included Lieut. Thomas B. Lofthause, in charge of the motor squad of which Bayer was a member; Nat Rothstein, advertising director, and Harry Blanchard, sound-recording engineer of Columbia Pictures Corporation.

::

Bayer’s Hollywood friends later organized a fundraiser to help the Bayer family.

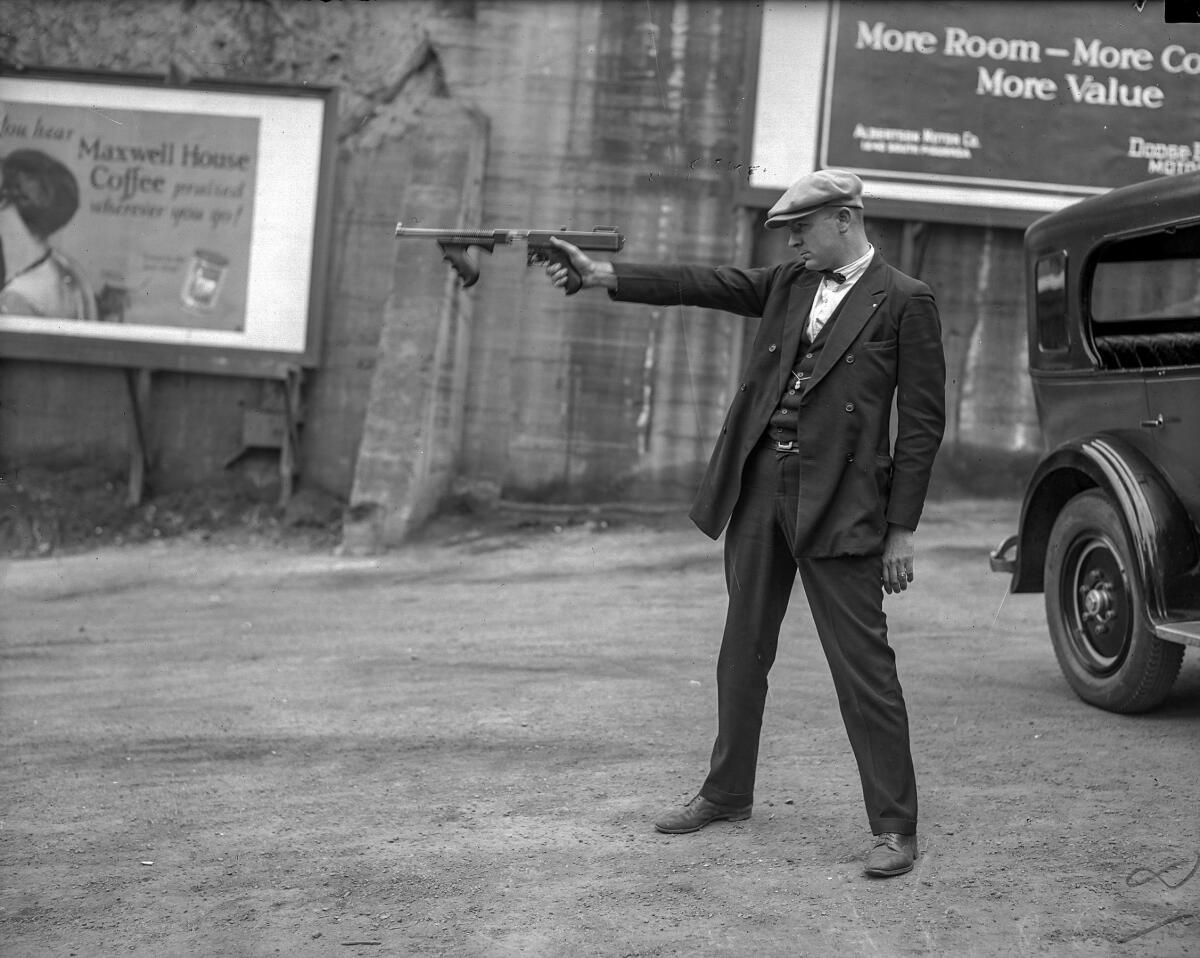

The two photos of Bayer and other officers posing next to a car were unpublished. The exact date of the images is unknown but were taken a couple of years after the 1925 shootout. The car, a 1926 Studebaker, was identified by Earl Rubenstein, curator at the Automobile Driving Museum in El Segundo. The car also has 1927 California license plates. The names attached with the negatives identify Bayer’s rank as a detective lieutenant.

I suspect the two circa 1927 photos were taken to promote some aspect of the Los Angeles Police Department’s new “flying squads.” The LAPD established these units to provide rapid police response. An Oct. 16, 1925, Los Angeles Times article reports on the transfer of 23 policemen -- including Bayer -- to the new “flying squadron detail organized to combat the influx of Eastern gunmen.”

This post was originally published on May 31, 2013.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.