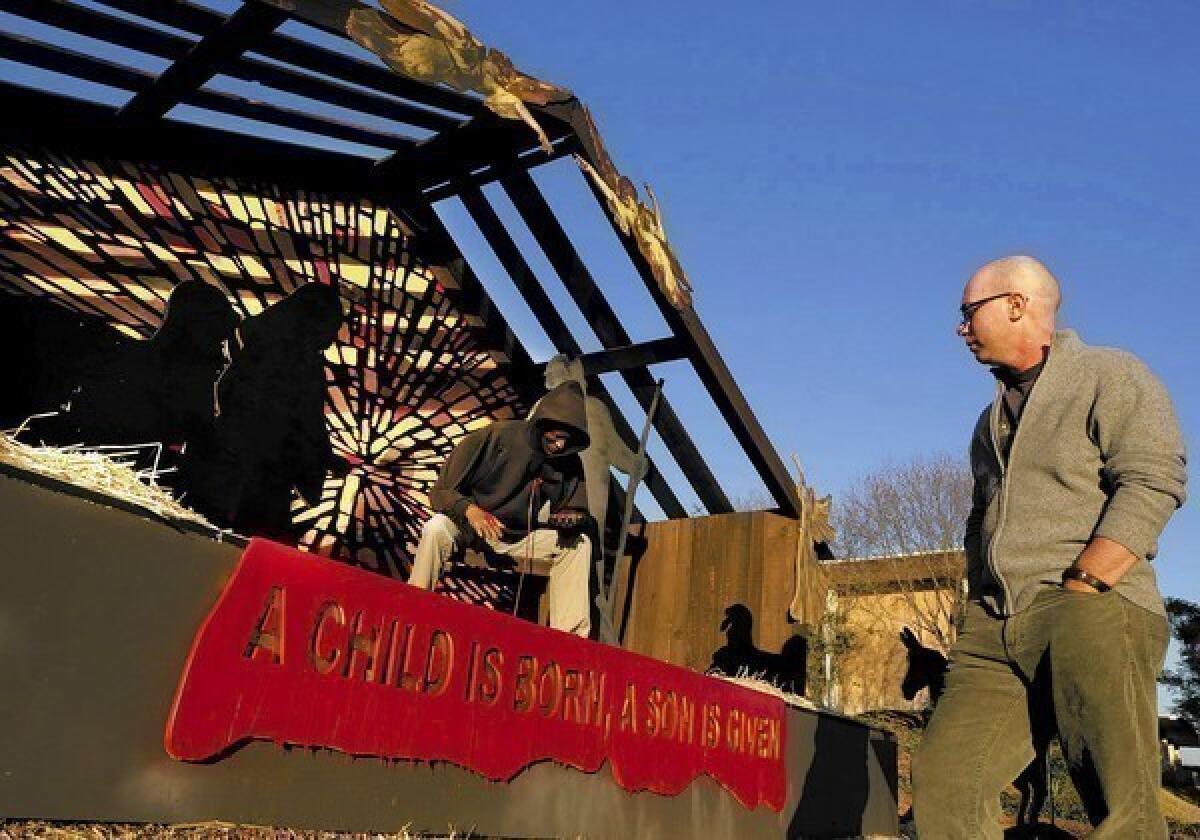

Nativity scene with Jesus, Mary and Joseph in cages makes people uncomfortable. But that’s the point

It didn’t surprise the locals when Claremont United Methodist Church unveiled its annual outdoor Nativity scene this week. In keeping with its spiritual leanings and activist traditions, this was no tender Christ-child-in-the-manger tableau.

Instead, Joseph, Mary and the baby Jesus had been separated and locked up in individual chain-link pens, topped by barbed wire fencing.

What shocked people in this suburban L.A. County college town was what happened next: An image of the scene posted online by the Rev. Karen Clark Ristine ricocheted across the country. Propelled by social media, it was showcased by virtually every major media outlet and drew a mix of outrage and applause.

The Nativity scene was intended to reflect the plight of immigrants and asylum seekers whose families were separated on our southern border — a process many in the church consider a moral abomination.

“We don’t see it as political; we see it as theological,” Ristine told Times reporter James Queally. But tens of thousands of people around the U.S. didn’t see it that way.

The image has sparked a heated national debate about spiritual boundaries and moral commitments. Its caustic tenor online reflects the state of dialogue in this country today: warped by political divisions, riddled with gratuitous insults and sabotaged by self-righteousness.

The pastor’s initial Facebook post was shared more than 24,000 times and drew more than 14,000 comments. Responses ranged from the grateful to the profane.

The church was lauded for taking a bold and compassionate stand on one of the country’s most divisive issues. “It’s a perfect comparison. Some people just don’t want to hear or see the truth. In my world there are no ‘illegals.’ Thank you for your courageous and profound statement,” wrote one woman in Beverly Hills.

And the church was slammed for inserting politics into what should be an innocent season of goodwill. “May the Heavens send fire to take down your church when it’s empty,” one self-identified Christian wrote, adding a praying hands emoji.

And as everything seems to do these days, the debate ultimately morphed into a referendum on Donald Trump, replete with ugly memes disparaging immigrants and promoting white supremacy.

The venom the image generated shook the church community — particularly given the fact that Claremont Methodist has for several years celebrated Christmas with unconventional Nativity scenes built around social justice themes.

In its first departure from the Nativity norm in 2007, Joseph and Mary were a modern homeless couple on a ghetto street. The next year the Holy Family was depicted as war refugees in bombed-out Iraq. In 2009, they were Mexican migrants, halted by the U.S. border wall. In 2010, Mary was an African American woman holding her infant, alone in a prison cell.

Since then, the church has moved beyond Christmas liturgy to take on LGBTQ issues and racism — including one Nativity scene with no Holy Family but two same-sex couples and the label “Christ is Born,” and another featuring Joseph and Mary huddled over their baby, a hoodie-clad Trayvon Martin with blood streaming from his chest.

Those drew some backlash. But nothing like this.

Suddenly the 60-year-old church with 300 members became a national poster child for a progressive spiritual movement recognizing the political dimensions of religion.

I understand the discomfort some people feel when the innocent image of the Nativity is recast to spotlight troubling moral issues.

We tend to look at Christmas — the Christmas in our mind, not the one unfolding at the mall — as a respite from the rigors of real life. We turn down the news, turn up the Christmas music and try to cling to the holiday’s essential meaning: Hope. Peace. Goodwill. Joy to the world.

We don’t want to disturb our cookie baking and home decorating with graphic reminders of the cruelty unfolding in our country, on our watch. We don’t want to think about the wrong being done to strangers in our name.

When I look at those caged Nativity scenes, I can’t help but feel a sense of shame. My prayers seem puny; my guilt unearned yet unassuaged.

It’s uncomfortable, but that’s what these Nativity scenes are intended to do: disturb us enough that we don’t let holiday trimmings obscure the need to act against the unjust and inhumane.

Claremont Methodist isn’t the only church, now or in the past, to recast the classic Nativity scene to bring political issues to the fore.

Two years ago, a Catholic church in a Boston suburb made mass shootings part of its Nativity theme. This year it features the infant Jesus floating on water littered with plastic bottles, as the three wise men try not to drown. “God so loved the world,” it says. “Will we?”

And across the country, Protestant churches in Oklahoma, Illinois and here in Los Angeles are being praised and pilloried for Nativity scenes that use fences to cast Jesus, Mary and Joseph as mistreated modern-day immigrants.

“People say, ‘You’re just making a political statement, keep politics out of church,’” said the Rev. Keith Mozingo, pastor of Founders Metropolitan Community Church near downtown L.A. “But this is not a political statement. It’s a humanitarian voice.

“We can’t believe that people are coming here seeking asylum and we’re putting them in cages … and taking children away from parents who go months without knowing where their children are. I can’t believe this is America,” he said. “That’s unconscionable to me.”

This is the second year that his church has displayed the Holy Family in cages. He was braced for pushback, but there’s been very little, he said. A few conservative parishioners were outraged and will no longer attend, and a handful of ugly phone calls have come in.

“But for the most part, people understand; this is part of our commitment,” Mozingo told me. His church is rooted in the LGBTQ community. “We’re a very diverse congregation. … There are no outsiders here.”

But even here, some are wrestling with the feeling that however well-intended the gesture may be, it is hijacking a holy season to promote a secular agenda.

“This is such a sad situation and my heart breaks for those separated,” one of Mozingo’s Facebook followers wrote. “However, I think this display is so disrespectful to our Lord and Savior. Perhaps you could share this message in a different way.”

Mozingo said he understands the sentiment. He remembers his Pentecostal family’s reverence for the Nativity scene he’d help his mother set up every year.

“But if this causes a negative reaction, I’m OK with that,” he said. “At least they’re forced to think about it. … I’ve done what I’m supposed to do. Now let the Holy Spirit do what he’s going to do.”

Theologians suggest there is something about the classic Nativity scene that tends to conjure a sense of the sacred, even in people who aren’t overtly religious. It’s considered one of the central images of Christianity, as potent a symbol as the Crucifixion.

That’s what makes the Nativity feel untouchable to some — and like the perfect vehicle for a message to others.

Even the Vatican has gotten in on the act. Three years ago, its Nativity display included a small dinghy and figures from a Maltese fishing village, to represent, the Vatican said, “the realities of migrants who in these same waters cross the sea on makeshift boats to Italy.”

For Mozingo, reminding people about the need to act against the wrongs of the world trumps whatever divisiveness the new Nativities might breed. “It’s not about who’s in office and what party they are,” he said. “From a moral point of view, from a spiritual point of view … I can’t imagine in what world this is OK.

“I know we all want to have that sweet family Christmas. But there are hopeless people all around us, and we can’t pretend that they don’t exist.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.