Financially strained and low on supplies, community clinics help fight the coronavirus

Three days ago, Precious Williams began to feel sick. The young pregnant mother had a runny nose, a sore throat and shortness of breath — just some of the symptoms associated with novel coronavirus.

Concerned for her unborn child, the 22-year-old went to the Watts Health Center in South L.A. like she always has for her medical needs.

“I’ve been coming here since I was a child,” she said. “It’s where I’ve gotten all my shots, where I got all my dental done — everything.”

“These clinics are very important for people around here,” she added.

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, community clinics and health centers in Los Angeles County have helped mitigate the spread of the virus and prevented sick patients from overwhelming hospitals, which don’t have enough beds, staffing or protective gear to treat a flood of patients.

Community clinics that typically handle primary care including checkups and prescribe patients insulin for diabetes or medicines for their high blood pressure have been canceling their regular appointments and seeing more patients with symptoms that match those of the coronavirus.

Clinic leaders say they know they play an important role in reducing the impact on overloaded hospitals, but worry about not being able to provide the necessary primary care to their communities.

Plus, clinic healthcare workers say they too are running low on masks, gowns and other equipment they need to protect staff against the novel coronavirus. Even for them, a virus surge could eventually force them to close their doors.

Intensive care beds at Los Angeles County’s emergency-room hospitals are already at or near capacity, even as those facilities have doubled the number available for COVID-19 patients, according to data obtained by The Times.

That is why public and health officials ordered Californians to stay home in an effort to create social distance among people to help “flatten the curve” of the disease’s spread and provide much needed relief to hospitals.

“Even if half of Californians end up with the coronavirus, if it’s spread out over six months, then it’s more likely there will be appointments and walk-in clinics and ventilators at hospitals to treat everybody who is at that level of need,” said Steven Wallace, a professor in the community health sciences department at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health. “If it all happens in six weeks, then the lines at the clinics will look like the lines out of Costco.”

The Watts Health Center had been open for only an hour when Williams and nine others sought urgent-care services on a recent rainy Thursday morning. They all reported having flu-like symptoms; more patients would come later in the day.

Community clinics and health centers are a vital part of the country’s healthcare system but the current crisis has created revenue and resource challenges.

“The normal routine of a community health center is very different than what they’re being asked to do right now,” Wallace said. “They’re set up for primary care, they’re set up for a child coming in with an earache or an adult coming in for diabetes. They’re not set up for a contagious pandemic.”

“They don’t have a stockpile of masks for their providers to wear,” he added.

In Los Angeles County, more than 350 community clinics and health centers provide primary care and preventive services to 1.7 million patients a year, many of whom live in poverty or are uninsured, said Louise McCarthy, president of Community Clinics Assn. of Los Angeles County, a coalition of private and non-private community centers.

Unlike hospitals, clinics aren’t equipped to have ventilators, but they do have test kits. But McCarthy said clinics and health centers are facing a shortage of such kits and other supplies.

“There are not enough masks, there are not enough gloves, gowns, goggles and all of that,” McCarthy said. “It’s a challenge. Every day we’re trying to get a delivery of supplies.”

She said some facilities have to turn to private sellers such as Amazon to obtain supplies, spending more than what they normally would. And with a small stock of test kits, doctors reserve testing based on the criteria set by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Sion Roy, president of the Los Angeles County Medical Assn., said the physicians group has tapped into membership dues to purchase $100,000 worth of masks and other personal protective equipment for doctors and nurses.

The association is working with vendors to set up a more efficient supply chain and has asked any of its 7,000-plus member physicians to apply for financial assistance for the supplies on its website.

“We are just trying to do whatever we can do to help, but it is a real challenge,” Roy said. “Across the county and across the nation, it’s a crisis.”

McCarthy said many of the clinics and health centers have had to scale back services and tell patients not to come to the clinic or center unless they’ve been told to by their doctor or if they have an emergency.

“But that means they have seen a significant drop in the numbers of visits they have per day and that then connects us to a revenue problem, which is that clinics get paid by the visits,” she said. “If you’re not providing visits, you’re not getting paid and how do you pay your staff?”

Public health officials have urged doctors to take visits over the phone or video conference. But for federally qualified clinics and health centers getting reimbursed by Medi-Cal, the state’s version of Medicaid, that is currently not available. McCarthy said state and federal officials are working to make it possible. She said she worries that some clinics may end up closing in the end if the situation doesn’t change.

“It’s really scary times for us right now,” she said. “We want to be open to the public and provide services and make sure patients get everything they need but also make sure our employees stay employed and have the health benefits we provide and the income that we provide them so they can pay their rent.”

Doctors and nurses at clinics and health centers said they worry about the impact this crisis will have on the preventive care they have made a priority in low-income communities, where diabetes, mental health issues, heart disease and other problems are common.

The outbreak has forced the Watts Health Center, one of seven clinics operated by the Watts Healthcare Corp., to make organizational shifts while putting a strain on the clinic.

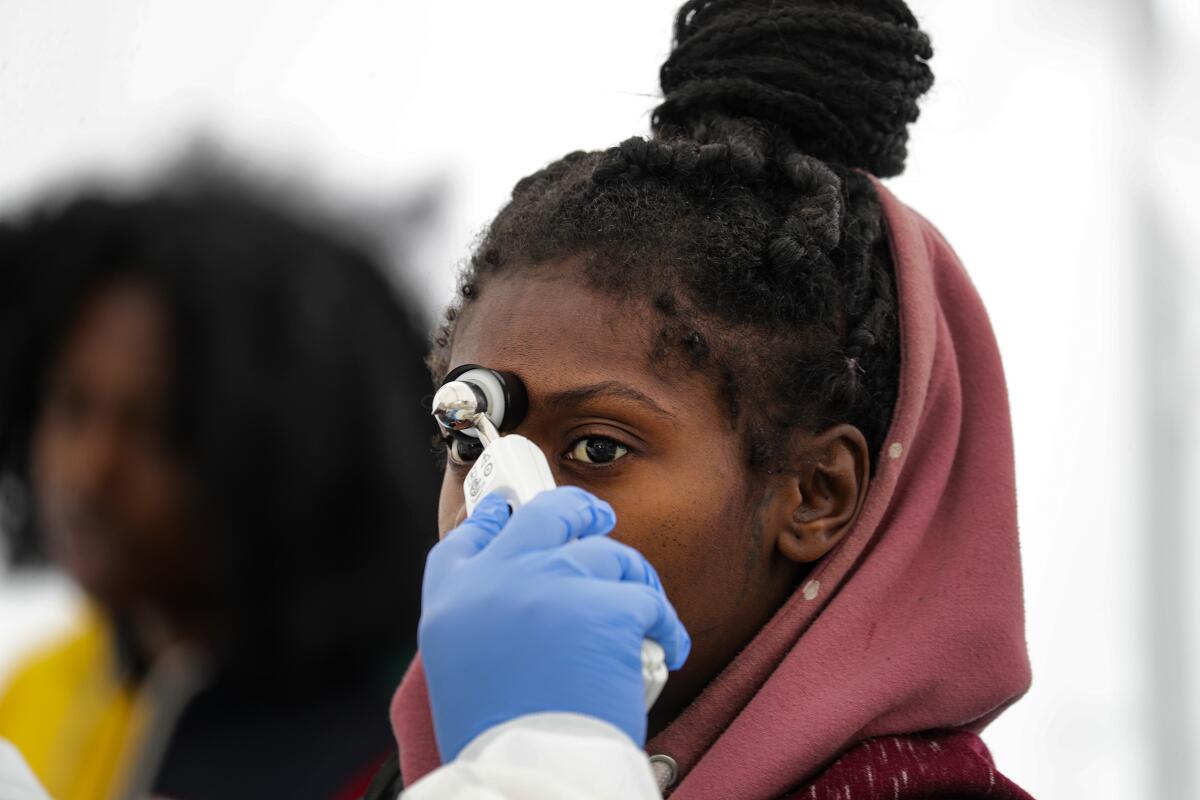

Dr. Roderick Seamster, president of the corporation, said the clinics are still seeing patients diagnosed with HIV, diabetes and parents who need WIC, the federal nutritional program for women, infants, and children. They’ve implemented a strict screening of patients and staff at every entrance. Many of the patients are told to sit outside if they have symptoms of the flu.

Seamster said the clinics are located in low-income neighborhoods, including housing projects such as Nickerson Gardens, Jordan Downs and Imperial Courts. The Watts Health Center provides an array of services, including dental, vision, pediatrics and a substance abuse program The center has two mobile units that provide free HIV testing and mammograms, both of which have been placed on hold because of the coronavirus.

Despite the distress the center has faced, Seamster said it has not turned anyone away. The clinic has about 30 kits to test for the coronavirus. So far, based on the criteria it is following, the clinic has performed very few tests — and none have turned up positive for the virus.

“Even if we don’t have enough resources, we share the ability to refer patients to a coalition of clinics,” he said. “We look out for each other to get it done.”

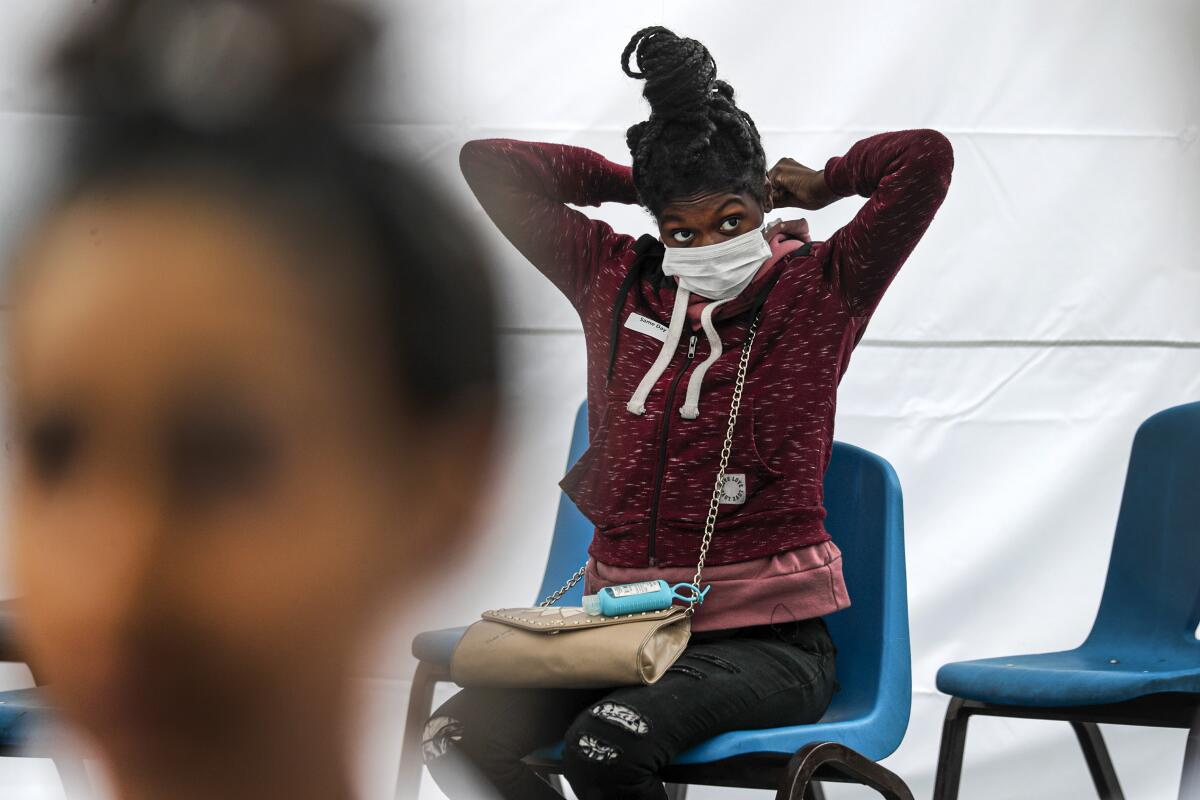

As rain pelted the white triage tent outside the Watts Health Center, Williams, the young expectant mother, sat on a blue chair wearing a surgical mask. Nearby, three children were coughing while two teens sat leaning forward with their heads down, each suffering from a sore throat.

Struggling to breathe, Netia Jones, 58, said she had asthma and needed a nebulizer that the clinic had.

“I don’t want to be here because of the virus,” she said, breathing heavily. “I’m afraid of it.”

Nearby, slouched on a chair and wearing a mask, was Ada Gomez, 59, who came to the clinic to get a second opinion about her illness. She had a dry cough, a fever and the sore throat. She went to St. Francis Medical Center in Lynwood, worried that she was infected with the coronavirus, but the doctors told her she didn’t meet the criteria for testing and to stay home.

Gomez said she wanted to get a second opinion from doctors at the clinic.

“We have great doctors here,” she said. “I’ve been coming here for four years.”

Times staff writer Ben Poston contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.