Reopening California schools: 4 things you need to know

Could an early reopening of schools over the summer offer students a chance to catch up with work while offering parents a much needed respite from schooling at home?

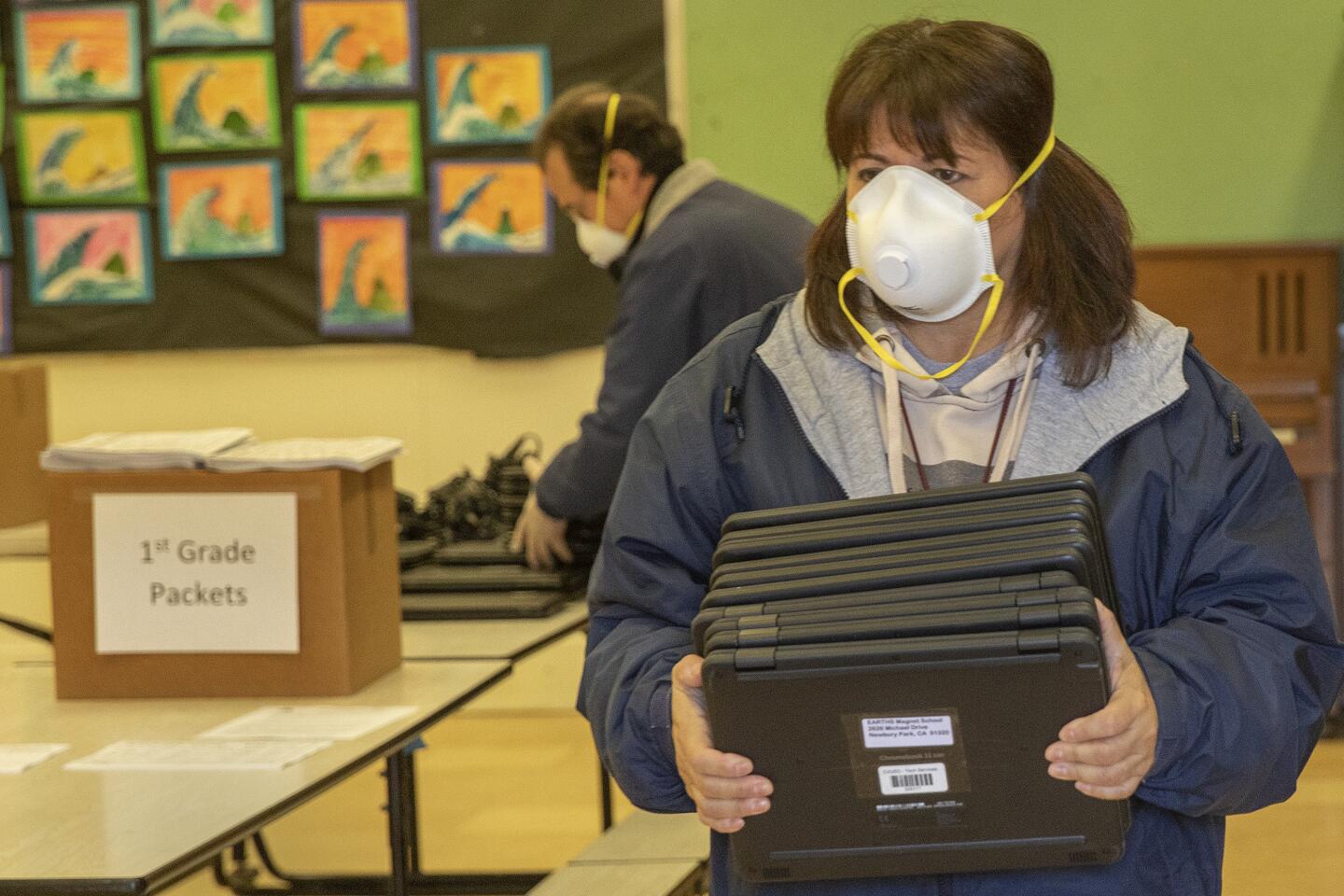

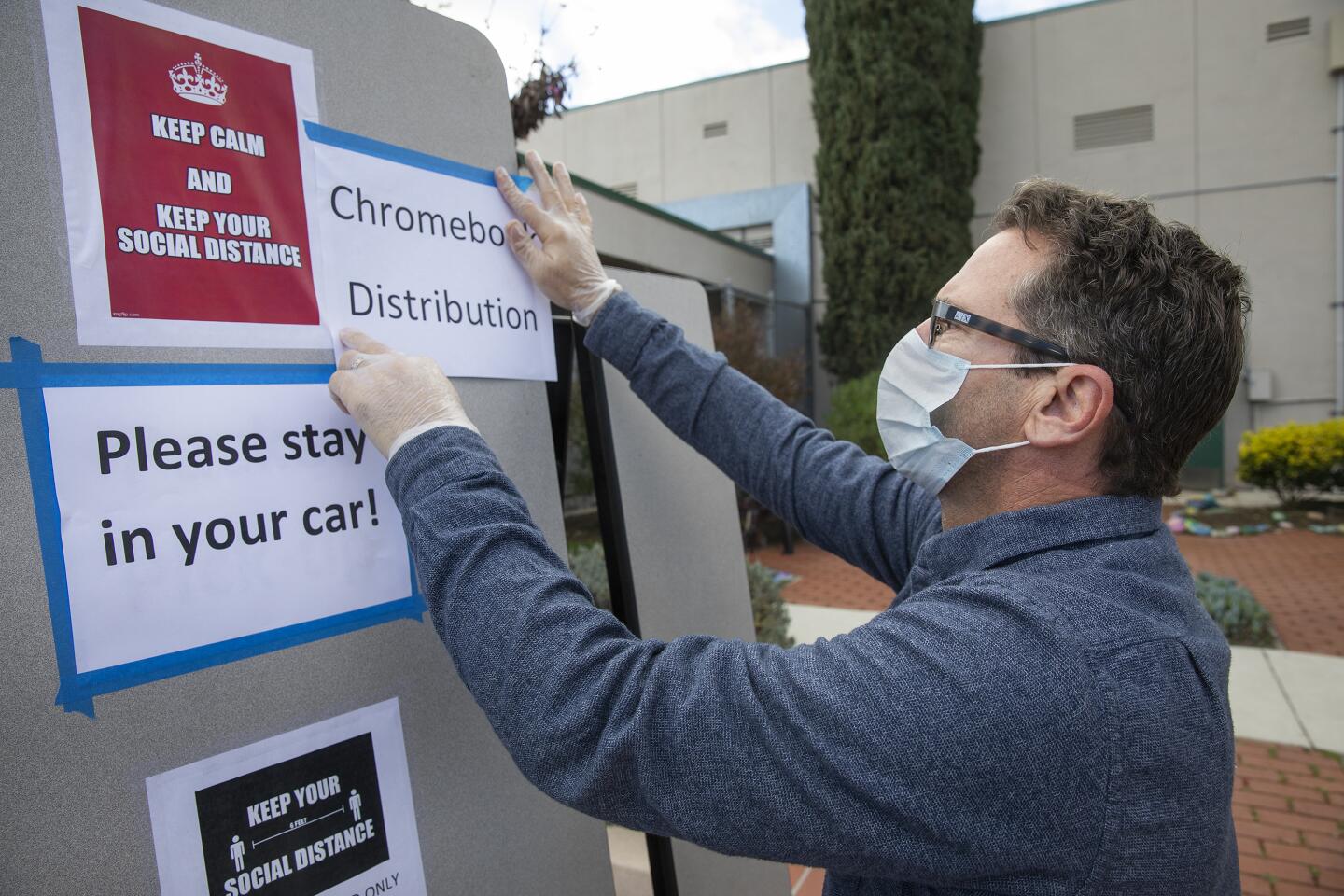

With about 6.1 million California students shut out of their campuses since about mid-March amid the coronavirus crisis, Gov. Gavin Newsom said Tuesday that public school might be able to reopen their doors by late July or August. The plan is high on ambition, but low on details.

On Wednesday State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond said is it not yet known “exactly when school can start and we will not ask the schools to start until it is safe for everyone.” Reopening decisions will be made at the school district level and the state will help provide the resources and supplies to support campus operations, he told a parents and others attending an education webinar.

He also said a working group of state leaders will study reopening and said that some form of remote learning may still be needed. Local district officials caution that health and safety measures are far from being in place and teachers union leaders expressed concerns about the possibility of early openings, saying workplace changes are subject to bargaining.

School districts throughout the state are just now beginning to assess how to reopen what are almost certain to be reconfigured campuses and schedules to protect the health of students and staff.

Here are four things to know:

1) ‘As soon as possible’ is a goal amid uncertainties

Newsom said officials hope to reopen K-12 campuses as early as it is safe to do so and, given the stakes in lost learning, suggested that late July might be possible.

It is still unclear what a reformatted school day would look like, and how educators would enforce social distancing and ensure enough disinfecting supplies and protective equipment to conduct instruction without excessive risk.

“If this is going to work, there are some major questions we will have to answer,” state schools Thurmond said in a statement. Among them: How will school systems keep everyone on their campuses safe and healthy? How will schools pay for teachers and resources to allow for the smaller class sizes that social distancing requires? Could a school day split between time on campus and distance learning be the answer? But then what would the ramifications be for working parents in need of child care?2) Schools will have to operate differently.

Social distancing — keeping six feet apart — is going to be challenge.

But educators know they will have to retrofit both schools and procedures to make it work.

Palos Verdes Peninsula Unified School District Assistant Supt. Brenna Terrones on Tuesday talked about needed supplies. Alcohol and Lysol-type disinfectant products have been nearly impossible to find. The district has 16 boxes of surgical masks for health staff. An order of face masks is supposed to arrive in mid-May; opinions differ on whether they should be mandated. There’s probably a six-month supply of gloves. Thermometers are on back order.

Supt. Alexander Cherniss asked whether the district should install portable hand-washing stations and require students to wash their hands several times a day.

“Can we legally take their temperature before they enter campus” with no-touch thermometers? he asked. The answer was murky — yes for adults in a pandemic, said Diane K. Wagener, a health statistics and policy specialist in attendance. But she was not immediately certain about the legal parameters regarding students. Many children could be infectious without showing symptoms, she pointed out.

While school board President Suzanne Seymour said having 30 to 35 students in one classroom would be a “tough sell” for parents, Cherniss said reducing class size for safety reasons or to offer more academic support “was almost an impossible task.”

“Principals, please start thinking about ways to reduce class size, ways to alter schedules,” he said. “Start thinking about those kinds of concepts.”

3) Students are suffering under the current situation

Newsom was clear he wanted students back in school as soon as it is safe.

“We recognize there’s been a learning loss because of this disruption. We’re concerned about that learning loss even into the summer,” Newsom said. “Our kids have lost a lot with this disruption. ... And you can either, you know, roll over and just accept that or you can do something about it.”

The magnitude of learning loss because of the closures is unclear, researchers said. A brief this month applied summer learning loss research to the current pandemic to provide possible answers. In one scenario, the report found that students could experience a “COVID-19 slowdown,” in which they would not see gains or losses in reading and math from mid-March until the fall.

In another, more troubling projection, students would suffer a “COVID-19 slide,” in which they return in the fall with just 70% of the learning gains in reading that they would typically see in a school year, and less than 50% in math.

“We’re kind of assuming ... in the slowdown projection that new materials are being offered but the new learning is not continuing at the rate that it should,” said Megan Kuhfeld, a research scientist at the NWEA and coauthor of the brief.

“You think about the long game ... this is potentially a COVID-19 generation that is going to be playing catch-up for many years,” said coauthor Beth Tarasawa, NWEA’s executive vice president of research.

4) Money and equity are other issues

An early start to the school year, the brief said, could be complicated logistically, financially and academically — especially because the state’s plummeting tax revenue could lead to budget cuts and because shutting down campuses has exacerbated existing challenges in educating low-income students and those with disabilities.

In recent years, summer school was sharply cut back to save money — becoming substantially a vehicle to help seniors fulfill graduation requirements and relatively small numbers of students with special needs. Districts across the state are trying to develop a robust program this summer for all students, but still using distance learning. Such a program would require increased funding to pay teachers and other staff.

In L.A. Unified, the school board approves the academic calendar, but an extended school year would require negotiations with employee unions.

“Our 75,000-plus employees serve the needs of almost 700,000 students who live with another couple of million people,” L.A. Unified Supt. Austin Beutner said Monday. “Will [coronavirus] testing be available for all of these individuals and who will pay for it? That’s the sort of challenge which lies ahead.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.