Many California farmworkers fear a winter of hunger and homelessness amid the pandemic

In a year without pandemic, fire and extreme heat, Jose Luis Hernandez by now would have saved enough money picking summer fruit from California fields to make it through the slow winter months ahead.

This year, he is in debt to a friend and does not know how he will provide food and shelter for his wife and three sons as the final grapes are taken from the vines.

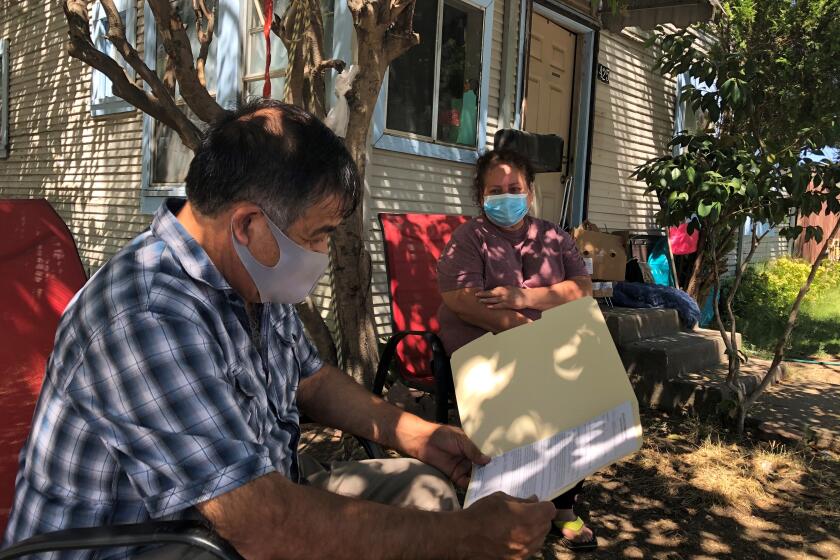

“I haven’t saved anything,” he said, sitting on the walkway of an aging five-plex in south Stockton, one of the poorest neighborhoods in this San Joaquin valley city, where he pays $675 a month for an apartment with taps that sometimes spew black water.

“You have a puzzle, electricity or your refrigerator is empty,” he said. “I am worried.”

Hernandez, said other agricultural laborers and advocates, is one face in an imminent crisis confronting the state’s farmworkers here illegally. Though they have been declared essential for the state’s multibillion-dollar agriculture industry, they often don’t qualify for safety nets such as unemployment, eviction moratoriums or stimulus aid that have become lifelines for many as they weather a crushing year of disasters.

Familiar with the seasonal nature of farm work, most field laborers conserve earnings from earlier months to plan for the cold season when fewer people are needed for tasks such as pruning. But this year, there has not been enough work and many are dreading a winter of scarcity.

Already, the coronavirus has sickened many agricultural workers, and sent others home to quarantine, often without pay despite new rules offering it.

Schools closed, leaving many families scrambling to meet unexpected childcare costs, or forced some to quit jobs to stay home with young children.

Fires in Napa and Sonoma, where many San Joaquin workers including Hernandez commute, left laborers rushing to save what they could of harvests under orange skies. But there too, work was cut short by weather and danger.

The effects of the pandemic and wildfires were worsened by months of record-breaking heat that raised electricity bills as window air conditioners strained to keep triple-digit temperatures at bay and left fields unsafe during the hottest parts of the afternoon.

Now, with few protections and little government aid, many are afraid the worst is yet to come.

“It’s not looking good for families here in the valley,” said Elvira Ramirez, executive director of Catholic Charities of the Diocese of Stockton. “These families are going to be in big trouble.”

A Times analysis found the San Joaquin Valley remains hard hit by the coronavirus even as other parts of the state see risk levels drop, and Latinos are more than three times as likely to test positive for the virus as white counterparts. Statewide, about 61% of cases and 49% of deaths are among Latinos, though they make up about 39% of the state’s population.

Essential Latino workers here illegally also remain some of the hardest hit economically.

Nearly 80% of California’s workers without legal status are in jobs deemed essential, according to a UCLA study released earlier this year — and about 50% of farmworkers lack legal status. On average, those workers lost 25% of their wages between February and April — more than any other demographic of employees. Little has improved over the summer, according to interviews with workers and advocates, even as some communities begin to reopen.

Up to 70% of new cases of coronavirus in California’s fertile San Joaquin Valley may be Latino workers, but advocates say they lack testing and access to care.

So far, the crisis facing farmworkers hasn’t yet triggered a dip in agricultural output. Although some sectors, including wine and dairy, have racked up losses, fruit and vegetable production in California is on par with last year’s quantities, according to a survey of U.S. Department of Agriculture data. That yield, said some experts, should translate to the same amount of work for laborers — though in recent years, employers have turned to more temporary visa holders and mechanization, both trends accelerated by the coronavirus.

“The expectation at the beginning was labor shortage, labor shortage, labor shortage — that did not come to pass,” said Philip Martin, professor emeritus of Agricultural and Resource Economics at UC Davis and author of the survey. “It’s not as if there’s much less work to do out there. The peach trees are already planted and they are either going to pick them or not.”

But for those on the ground in San Joaquin, the statistics do not match their experience.

The Rev. Nelson Rabell-González, the regional leader of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, has collected and distributed more than $800,000 in direct cash in the San Joaquin Valley since the pandemic started, giving hundreds of families checks of up to $1,500. The money usually doesn’t cover even a month of expenses, he said, and taking it often means families disqualify themselves for some of the scant other options for aid. Yet he receives calls every day from workers growing increasingly desperate as they are unable to pay for basic necessities, he said.

He has given out about 770 checks so far and said it’s “the same story over and over: Food, rent, bills.”

Amalia Ortiz Santana, a farmworker currently working in sweet potato fields, recited that list in Spanish — comida, la renta, las facturas — when asked what her worries are for the winter.

“There is no extra help,” she said.

Santana is currently working near the town of Livingston in Merced County, where hundreds of workers in a Foster Farms meat processing plant contracted the coronavirus and county health officials said nine died. Santana took herself off the job for four weeks because she thought she had the virus earlier this summer, and now “owes a lot of money,” she said, waiting in front of a run-down white-steeple church where Rabell-González was passing out checks.

Next in line to Santana was Janette Jimenez and her daughter Janely, 5. Jimenez was cleaning houses, but now stays home to care for her four kids. Her husband tested positive for the virus not long ago, along with two of the children, though she has continued to test negative. Though her husband has recovered, “he feels different. He feels like he is not the same,” she said. They are behind on rent and their electricity bill, and have been going to a food bank weekly.

This winter is “going to be even worse,” she said.

René Lopez, a grape picker, came soon afterward. His cousin was hospitalized with COVID-19, and Lopez knows “it’s not a game.”

He said he has lost about half of his typical hours this year and has been unable to continue to send money home to support his parents in Mexico. He lent his cousin some money, but wishes he could do more, he said. He is two months behind on his $1,000 rent and his family has been forced to reduce the amount of food they buy.

In April, Gov. Gavin Newsom allocated $75 million in state funds to give up to $1,000 to 150,000 immigrant families here illegally. That aid was largely exhausted by July. Recently, Newsom signed a package of bills to provide further help for agricultural workers, including education about access to paid time off and workers’ compensation, and quarantine housing in hotels for exposed workers. But the recent round of bills did not include more direct financial aid, and with the Legislature largely done for the year and a budget shortfall forcing cuts, more state money is unlikely.

California Assemblyman Robert Rivas (D-Hollister), the grandson of a farmworker and chair of the Assembly Agriculture Committee, said the state “woefully underfunded” its response to workers in the country illegally.

“It just wasn’t enough,” he said. “We need to do better.”

Rivas and others have been pushing Newsom to create a system of regular payments during the pandemic for workers here illegally, increase access to Medi-Cal and offer families without legal status access to the Earned Income Tax Credit for low-income families. Many workers here illegally pay taxes despite their immigration status, he said.

Without those “basic social safety net” items, Rivas said, “it’s going to get much, much worse.”

Ramirez, from Catholic Charities, said the state needs to be more flexible with cash payments to reach workers without legal status. They are often fearful of authorities and deportation, and function in a gray economy devoid of leases, bank accounts and other official pathways that offer citizens both stability and protection, she said.

is the regional leader of Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and has collected and distributed more than $800,000 in direct cash in the San Joaquin Valley since the pandemic started.

When her organization first received state money for workers, it asked recipients for landlords’ contacts to send money directly to owners. But some clients balked, afraid of angering landlords who were renting under the table, she said, or rocking the boat on already tenuous living situations. The same was true of free hotel rooms — she found mistrust to be a barrier.

“There is the complexity of the mixed immigration status,” she said. “The pandemic has uncovered a lot of the problems that were already there.”

Farmworkers are also in danger of seeing their wages fall next year. The U.S. Department of Agriculture recently announced that, for the first time in decades, it will not do a fall wage survey for agricultural workers, a metric used to set wages for the coming year for migrant visa holders. The change could mean some workers would see their hourly wage drop to the state minimum. In California, that could mean a loss of between 77 cents and $1.77 an hour for some farm labor.

Migrant farm workers across California fear evictions as the coronavirus forces them out of jobs. Without legal status, they have few protections.

Last week, the United Farm Workers sued the USDA in federal court in Fresno, hoping to force the government to conduct the survey.

Diana Tellefson Torres, executive director of the UFW Foundation, called the federal decision “a slap in the face to farmworkers” to whom “every cent makes a difference.”

For Hernandez, the Stockton father of three who has worked in the fields since he was 17, taking care of the bills is a matter of pride. He wants to set a good example for his sons, he said, and teach them that “it’s important to pay the rent through the pandemic.”

He just doesn’t know how he will do it.

He has been turned away from aid agencies with no explanation, he said. When wildfire smoke canceled an end-of-harvest party at his last job, he asked if the workers could have the event money as a bonus. He received no answer, just a blue baseball cap celebrating the vineyard’s 50th anniversary.

“There are too many obstacles,” he said, as a candle burned on an altar just inside his front door. “My family, the family Hernandez, they are not receiving help.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.