The pandemic shaped my family for generations. Not COVID — the 1918 flu

A century from now, someone who has not yet been born will come to a haunting realization: Their life was shaped, in ways they may never fully understand, by the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020.

I know this, because it’s the story of my family.

It’s a story with unfathomable twists and turns, great pathos and heroism (not mine). It ends, like so many pandemic stories, with both heartache and humanity. And I have no doubt that versions of this mystery story exist in other families, though it’s entirely possible that they don’t know it and never will. There is no neat and simple end to a pandemic.

I grew up in Sacramento, the third child of what seemed to me to be a perfectly normal family. I had two loving parents, two much-older brothers, two grandmothers and one living grandfather, on my father’s side.

My paternal grandparents were Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe and spoke English with strong Yiddish accents that I found lilting and comforting, albeit decidedly foreign. My grandmother, Sarah, was warm and loving, an endless source of homemade cookies and home-cured pickles. We called her Baubie, an Americanized version of the Yiddish Bubbe. My grandfather, known as Grandpa Brown, was, like most grandfathers of the time, gruff but caring.

I spent a lot of time in their home, about a five-minute drive from my parents’ house. But I never asked questions. What was their life like in, as we always called it, the old country? What was it like to uproot and move to an unfamiliar land? Why did they move? Why did they never speak of the past?

I never asked. And soon it would be too late.

When I was an adolescent, in the mid-1960s, my grandmother had a devastating stroke. She lost all ability to speak, although she retained a limited ability to understand. That only compounded the curse, and visits to her inevitably ended with her sobbing in frustration at her inability to respond to what we said to her. Her condition broke my grandfather, who was the first adult man I ever saw cry. They moved into a nursing home in downtown Sacramento. It was the saddest place I knew.

One night at dinner, I asked my dad, Morrie, a seemingly simple question: What kind of father was Grandpa Brown when you were a kid?

“He’s not my father,” he replied.

I can still remember the weight of that sentence, which hit me like a wet sandbag. It would not be the last such sentence to have that effect.

“My father died in the 1918 flu,” my dad continued. It may have been the first time I’d ever heard of the Spanish influenza pandemic, which killed at least 50 million people worldwide. My dad would have been 5 at the time.

California lessons from the 1918 pandemic: San Francisco dithered; Los Angeles acted and saved lives

San Francisco went mask crazy. Los Angeles shut down early and stayed closed longer, but not long enough. Some lessons from the 1918 Spanish flu.

I knew that my dad had been born in San Francisco and later moved to Stockton and finally Sacramento as a boy. I knew his family had been desperately poor. I didn’t know much more than that — and he wasn’t going to enlighten me much further. However, he did tell me that, after his father’s death, his mother had married Grandpa Brown.

I was perhaps not the sharpest tool in the family’s shed. I had never questioned why my grandparents went by the surname Brown, whereas ours was Landsberg. Grandpa Brown had been born in Russia with the family name of Chereasky, and, according to family lore, had adopted what he considered an “American” name after immigrating. He also adopted a number of first names that he used interchangeably: John, Jack, Joe and Jake. He was like all of the Pep Boys rolled into one man.

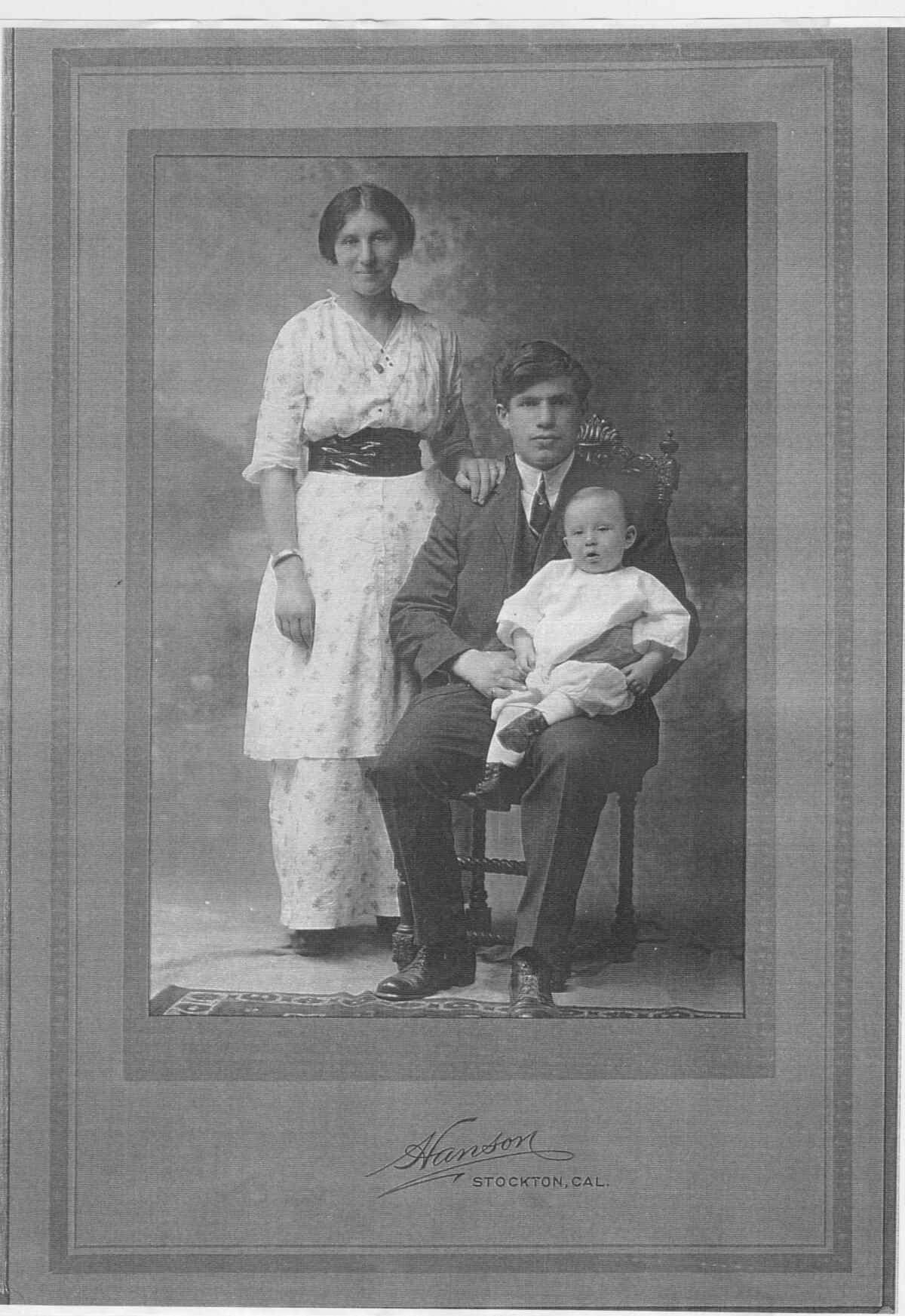

So what, I asked my dad, do you remember about your birth father? “I don’t really remember anything,” he said, “except that he was a very handsome man.” (When I later saw a photo of my grandfather, I had to laugh: He looked a lot like my father.)

The handsome man did have a name — just one first and one last name. He was Max. Max Landsberg.

Eventually, my grandparents would die, and life went on for the rest of us. I asked my dad a few more times about his birth father but never learned anything more. “I just remember that he was a handsome man,” he would say. The subject clearly made him sad, and after a while, I stopped asking.

My dad died in 1993, the morning after his 80th birthday. It was a poignant time for me. My dad had been 40 when I was born; I was 40 when he died, just weeks after my first son was born. It didn’t escape me that I was balanced precisely between the two of them — poised midway between life and death.

My dad was buried at the Home of Peace, the Jewish cemetery in Sacramento, where dozens of my relatives and close family friends are eternally resting (although there are inevitable jokes about the spouses who are eternally bickering). As we walked out after the funeral, I picked up a conversation with an aunt, the oldest of my father’s two sisters. I don’t remember why, but I made a reference to their father having died in 1918.

“He didn’t die in 1918,” she said.

The wet sandbag again.

“What are you talking about?” I said. “My dad said he died in the flu pandemic.”

No, my aunt said. He did get the flu in 1918. But he didn’t die. The high fever caused brain damage; he spent the rest of his life in the state mental institution in Stockton. At the time, there was a deep sense of shame surrounding mental illness.

So when did he die? I asked.

A week before you were born, she told me. She added that I was named after him — not exactly, but my parents chose an “M” name in memory of Max.

But how about my grandmother and my grandfather Brown? They had had a daughter together, my father’s youngest sibling. How did they get married when Max was still alive?

They didn’t, my aunt said. At least not right away. Shortly after Max died, they quietly took a bus to Reno and took their vows in secret. They had been together for decades at that point.

Decades later, I’m still processing this information.

The grandparents I knew — Sarah and Joe/Jack/John/Jake Brown — had been upstanding members of their community, stalwart members of their synagogue, with a close circle of friends. Yet, in the common parlance of the era, they had spent 30-some years living in sin. They had violated what was, at the time, one of society’s biggest taboos. It was hard to wrap one’s head around.

And their secrets haunted our family. My father could be very secretive, and whole chapters of his personal history were off-limits for inquiry. This could not have been an easy burden. He was a brilliant man capable of great humor, warmth and compassion, but the torment came out in his sleep — he was prone to horrific, thrashing nightmares — and when he drank. The drinking could bring out anger and a kind of existential dread.

I inherited some of his characteristics — the melancholia, the propensity toward secrecy. For a time, I drank too much. I’ve tried hard to overcome those tendencies, despite a powerful tidal pull that has been a century in the making. It’s probably not a coincidence that both my father and I became journalists — joining a profession that encourages its practitioners to keep their opinions and their emotions to themselves.

I mentioned heroism at the beginning of this piece. What I’m thinking of is my grandparents Brown, whose love triumphed over social pressure and who made a life, and nurtured a family, in the face of prejudice and overwhelming heartache. And I’m thinking of Dad, who persevered and became the father he lost, even as he battled the demons of deprivation and shame.

A few years ago, my brothers shared a childhood memory. As young boys, before my birth, they would sometimes go with my grandmother, Baubie, and my dad on weekend drives to Stockton. There, they would pull up to an imposing brick building and be told to stay in the car. My father and his mother would then go inside. When they returned, Baubie’s eyes would sometimes be red from crying.

My brothers never knew what they were doing in that building, but now we know: My dad and his mother were visiting a very handsome man, a tailor by trade, whose pandemic tragedy cast a shadow that lingers to this day.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.