California public school enrollment spirals, dropping by 110,000 students this year

California public school enrollment has dropped for the fifth year in a row — a decline of more than 110,000 students — as K-12 campuses struggle against pandemic disruptions and a shrinking population of school-age kids amid wide concerns that the decrease is so large that educators can’t account for the missing children.

California enrollment stood at 5,892,240 when measured in the fall of 2021, a 1.8% decline, according to state data released Monday. It is the first time since 2000 that the state’s K-12 population has dipped below 6 million, with large urban districts accounting for one-third of the drop.

While public school enrollment has experienced a downward trend since 2014-15, state education officials largely blamed the pandemic for the plummeting numbers over the last two years. This year’s decline, which includes charter schools, follows a huge enrollment hit during the 2020-21 school year, when the state experienced the largest drop in 20 years, with 160,000 students. In March 2020 the pandemic closed campuses in California and across the country, forcing schools into distance learning, many for nearly a year.

“One of the questions that we just have to come back to is, just where are those kids?” said Heather J. Hough, executive director of the Policy Analysis for California Education. “We don’t have satisfying data to answer that question.”

There was some expectation that enrollment would continue to fall, as the state faces declining residential population and birth rates, and out-of-state migration, said Julien Lafortune, research fellow at Public Policy Institute of California. But there was also hope in the education community that enrollment would show signs of rebounding from last school year’s massive loss.

“It doesn’t really look like that happened,” Lafortune said. “If anything, it looks like the declines are bigger than projected.”

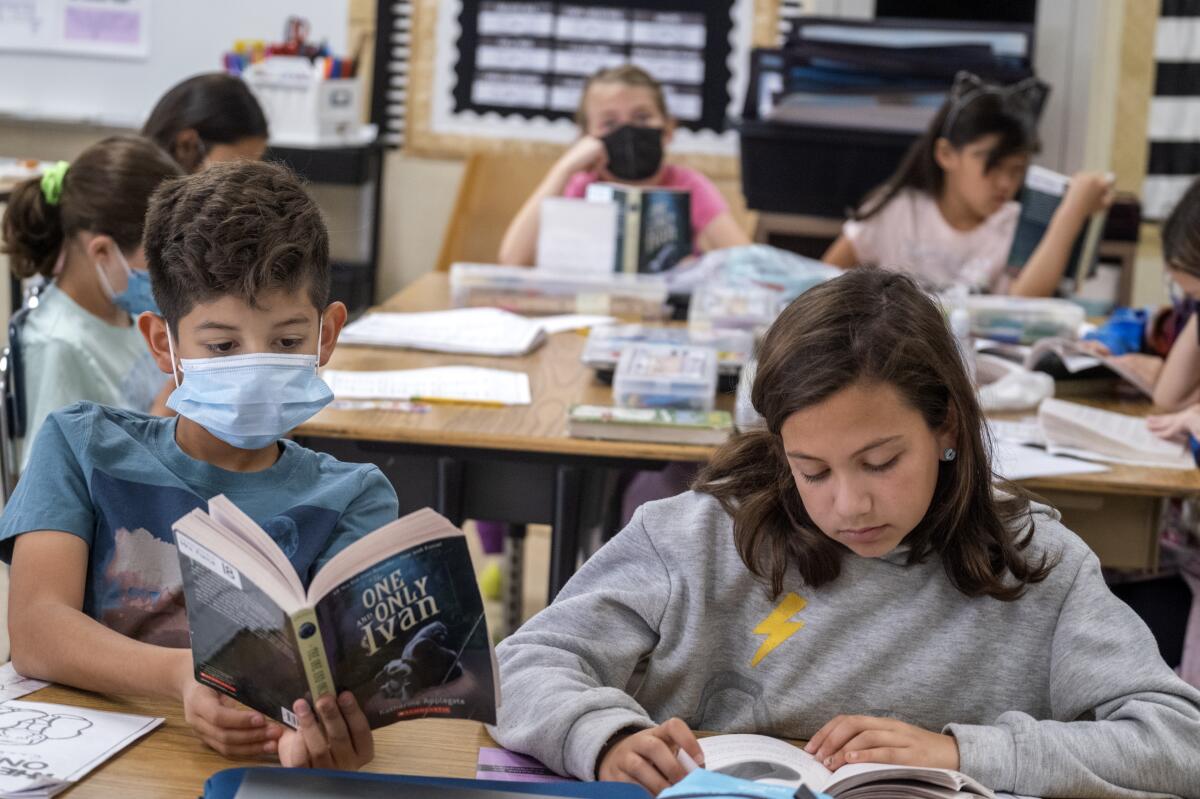

Several factors probably contributed to the falling numbers, experts said, although it is hard to pinpoint answers from preliminary state data. Some students entered private schools, which saw an increase in enrollment. Home schooling also increased as families either did not want to comply with pandemic safety measures such as masking or were concerned about the health risks posed by in-person learning.

Another potential factor is that more families may have moved out of California than expected, either because of rising housing costs or flexibility with remote work, amid other reasons.

But even these reasons do not neatly account for the big declines — and education experts are concerned that there are students who may have continued to stay out of the school system.

Statewide, the largest drops by grade level were among first-, fourth-, seventh- and ninth-graders. By race, the state saw the largest drop in enrollment among white students, a group that declined by 4.9%. They are followed by Black students at 3.6%, Asian students at 1.9% and Latino students at nearly 1%.

Though kindergarten enrollment improved compared with last year, it doesn’t make up for the steep loss in 2020-21, which saw a 12% decline. The state gained 7,756 kindergarten students this school year, a sign that some parents may have “red-shirted” their children and enrolled them in kindergarten this year after opting out last year.

There was also an open question as to whether parents would simply skip kindergarten and enroll their children in first grade, but that grade level was among those that experienced the largest decline this year.

“Those numbers suggest that wasn’t the case, either,” said Thomas Dee, a professor of education at Stanford University. A concern, Dee said, is “the possibility that a substantial number of the most vulnerable children are truant.”

Missing youths, by default, are hard to track, and it’s likely they are among more vulnerable subpopulations. Understanding where children went, experts said, is important for districts to begin planning for long-term solutions, including how to reach these children.

“Being able to plan for whatever comes next really relies on having some kind of sense of what’s happening with those kids, so they can be reached one way or another,” Hough said.

The state Department of Education is hoping to boost enrollment in transitional kindergarten and kindergarten classes and is providing districts with support to reach families of chronically absent students during the pandemic, which has worsened. In the Los Angeles Unified School District, the second-largest in the nation, nearly half of all students have been chronically absent, a Times analysis found.

Veronica R. Arreguín, chief strategy officer for LAUSD, said in a statement that part of Supt. Alberto Carvalho’s 100-day plan would be to analyze enrollment data and “develop a strategic plan to attract families back to our schools.”

“Enrollment changes seem to reflect the needs of families and students as a result of the pandemic, with 12th-graders needing additional time to complete graduation requirements and an influx of kindergarten students who might have been enrolled last year in our exemplary kindergarten and transitional kindergarten programs,” Arreguín said.

Charter school enrollment also dropped, down to 678,057 this school year, with a loss of 12,600 students. The California Charter School Assn. saw its largest decline in Alameda County.

Myrna Castrejón, chief executive and president of CCSA, said in a statement that charter campuses face the same demographic challenges as traditional public schools. The data “reinforces that charter public schools should be provided equitable funding,” Castrejón said.

Both enrollment declines and absenteeism signal potential financial difficulties ahead for many districts as school funding is based on attendance. Legislative fixes are under discussion.

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s budget proposes broadening the policy to allow districts to base funding on attendance in the current year, prior year or the average of that from three prior years — whichever is greater. State Sen. Anthony Portantino (D–La Cañada Flintridge) has proposed tying funding to annual enrollment instead of attendance. The legislation would also provide school districts with funding to combat chronic absenteeism and truancy.

Already, districts such as L.A. Unified and Oakland Unified are considering measures, such as school closures, as part of their effort to deal with the effects of falling enrollment. L.A. Unified saw a drop in fall 2021 by more than 27,000 students, an annual decline of close to 6%, a much steeper slide than in any recent year.

The decline is not unique to Los Angeles or California. But closures can be painful for the school communities involved, and solutions require collaboration as districts examine their costs and also serve the community, said Hough of Policy Analysis for California Education.

“What rapidly declining enrollment might be saying: Students, parents and families want something different from their schools,” Hough said. “There has to be solutions both that are cost-effective and meet the needs of communities, because that’s what we have to find in order to stabilize the system long term.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.