As fentanyl deaths surge in California, lawmakers kill bills that would punish dealers

As thousands of Californians die each year from drug overdoses fueled by fentanyl, a bitter fight has emerged in Sacramento over how lawmakers can hold dealers accountable without refilling state prisons and waging another “war on drugs.”

On one side of the debate are Republicans and moderate Democrats calling for stronger criminal penalties for dealers who sell the deadly drug, which is up to 50 times stronger than heroin and contributed to nearly 6,000 overdose deaths in California in 2021.

On the other are left-leaning Democrats who’ve spent the last decade retooling the state’s penal code to favor treatment and rehabilitation over long prison sentences, and who are reluctant to embrace policies they fear could devastate Black and brown communities.

The disagreement reached a boiling point this week at the state Capitol, as Californians whose family members died from fentanyl overdoses packed a hearing room where Democrats voted down a bipartisan bill that would require warning convicted fentanyl dealers that they could face homicide charges if they sell it again. Meanwhile, a Democratic lawmaker shelved several other bills to increase sentences for fentanyl dealers.

“I was around during the crack cocaine epidemic, and this is really very similar to the hysteria around crack cocaine,” said Assemblymember Reggie Jones-Sawyer, a Los Angeles Democrat who chairs the Public Safety Committee. “And we rushed to come up with a solution, instead of looking at it from both a public health crisis and a public safety crisis and to bring them both together.”

A desire to not repeat that history led him to shelve several fentanyl bills for the rest of this year, Jones-Sawyer said. He said many of the proposals focused on “how can we fill up the prisons again” instead of a long-term solution to addiction.

As California leads the fight to reverse skyrocketing fentanyl overdose deaths, organizations that distribute overdose reversal drugs worry their increasingly bold efforts to save lives will land them in legal trouble.

Jones-Sawyer said he wants the Legislature’s approach to align with recent funding and enforcement actions on fentanyl from Gov. Gavin Newsom and Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta. Newsom proposed nearly $100 million in the 2023-24 budget for prevention, treatment and education efforts, and expanded the California National Guard’s operations at the border. Bonta has also ramped up enforcement, leading to the increased seizure of fentanyl pills and powder.

The Legislature’s public safety committees have a record of sidelining bills that would lengthen prison sentences or create new crimes, because the Democrats who control them do not want California to incarcerate more people. But the severity of the fentanyl crisis has invited criticism of that commitment and forced a broader discussion over what role the criminal justice system should have in solving the problem.

“Fentanyl is causing an unbelievable number of deaths, and the trajectory is, unfortunately, headed in the wrong direction,” state Sen. Tom Umberg (D-Orange) said at a hearing for Senate Bill 44 before it was voted down.

The proposal would have required courts to provide a written admonishment to those convicted of fentanyl drug offenses, warning them of criminal liabilities if they sell a fentanyl product that kills another person.

In L.A. County, the number of deaths linked to fentanyl rose from 109 in 2016 to 1,504 in 2021, the county public health department found.

The proposal could make it easier to secure a future conviction, because the warning could be used as evidence for prosecutors to prove that a defendant was aware of the risks in drug dealing. It was modeled after the state’s DUI Advisory, which is used to deter repeated drunk driving. Two other versions of the bill have failed to pass the committee in recent years.

State Sen. Rosilicie Ochoa Bogh, a Yucaipa Republican who co-authored SB 44 , fought back tears during the hearing as family members spoke of those lost to overdoses. She said she was “heartbroken” by the bill’s defeat.

“Make no mistake. A policy like SB 44 would make a difference,” Ochoa Bogh said.

Umberg asked for reconsideration of the bill, which means it could soon get another vote. But he’ll likely have to accept an amendment proposed by Democrats to limit the bill to dealers who explicitly know they are selling fentanyl or laced products — a recommendation he has so far rejected.

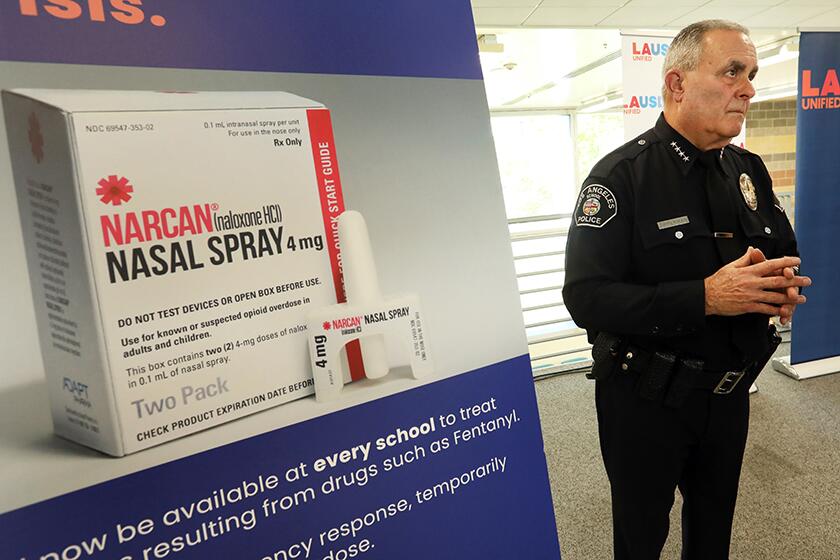

Under newly proposed legislation, Narcan could be required at California schools after spate of youth fentanyl overdoses.

State Sen. Steven Bradford (D-Gardena) said the proposal was reminiscent of the tough-on-crime era of the 1980s and ’90s that led to thousands of Black and brown people serving life sentences for drug offenses.

“Simply making it easier to prosecute someone for murder will not address or solve this problem,” Bradford said.

Jones-Sawyer plans to hold an informal hearing this fall, when the Legislature is not in session, at which everyone who has a stake in solving the fentanyl crisis will have a seat at the table, he says. That means holding off until then on considering legislation like Assembly Bill 367, which would have increased criminal penalties for those who sell, furnish, administer or give away fentanyl products that result in great bodily injury.

“I felt like fentanyl is such a serious issue that it could pass the committee,” said Assemblymember Brian Maienschein, a San Diego Democrat and author of AB 367.

Parents whose children died of fentanyl-laced pills are demanding stricter penalties and are lobbying Silicon Valley for social media protections.

Watching in the hearing room as the Senate panel killed SB 44 was Matt Capelouto of Riverside County. The bill is called “Alexandra’s Law” in honor of his 20-year-old daughter, who died after taking a fentanyl pill that she bought from a dealer on Snapchat while she was home from school for the holidays.

“What are the politicians of the Public Safety Committee, the people charged with protecting the lives and livelihoods of their constituents, actually doing? What are they doing about the drug dealers, the people responsible for knowingly jeopardizing the lives of the people they trade dollars for death to?” Capelouto said after the hearing.

“I’ll tell you what they’re doing,” he said. “Nothing.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.