Ernie Barnes’ ‘Sugar Shack’: Why museum-goers line up to see ex-NFL player’s painting

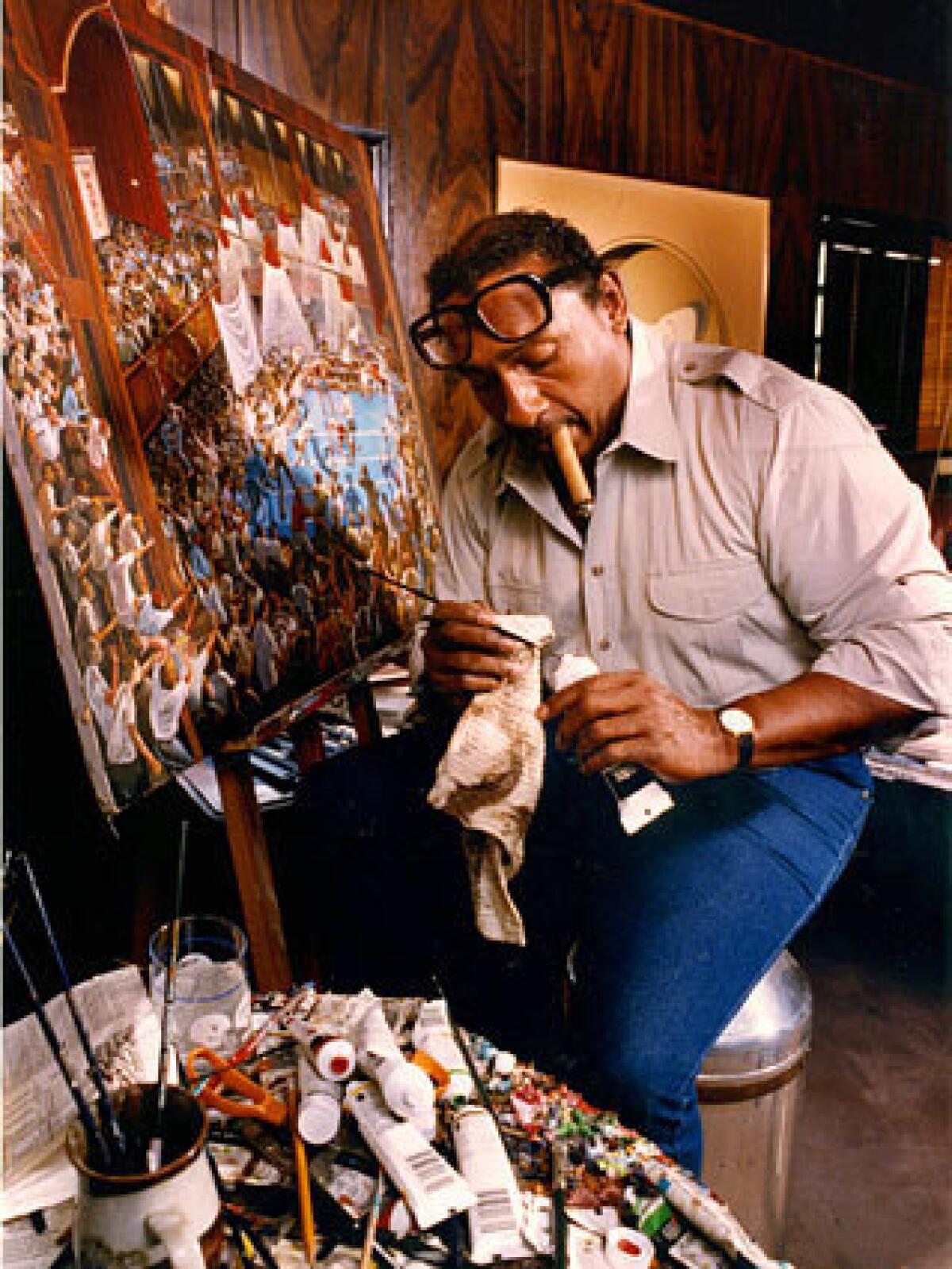

At the California African American Museum’s retrospective dedicated to late artist and former NFL player Ernie Barnes, “The Sugar Shack” is an undeniable star.

Visitors often form a line around the painting, said the show’s curator, Bridget R. Cooks, associate professor in the departments of African American studies and art history at UC Irvine. They all wait for their moment with Barnes’ work, a piece that entered pop-culture consciousness after appearing on the 1970s sitcom “Good Times” and as the cover art to Marvin Gaye’s 1976 album, “I Want You.”

“The Sugar Shack” transports viewers to a jubilant black club. Vibrant, dancing partygoers and musicians fill the 3-by-4-foot canvas. Most have their eyes closed, a signature in nearly all of Barnes’ paintings, referring to his oft-stated belief that “we are blind to each other’s humanity.”

As a neo-mannerist who referenced the late Renaissance period of Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael, Barnes painted the figures in “The Sugar Shack” as exaggerated and elongated forms, one man’s arms joyously nearly reaching the top of the canvas, another woman’s curvy legs stretching halfway across the dance floor. Barnes’ expressive style helps viewers identify with the rhythm and sensuality of the painting, Cooks said.

One central figure in the painting is a woman in a yellow dress and white shoes, dancing at the front of the tall stage, her back to the viewer. She’s a character who appears in artworks throughout Barnes’ career.

It’s easy to get lost in the revelers, but a closer look reveals unexpected details. Nestled in a corner between the stairs and the stage is a black man in a blue uniform, sitting with a newspaper at his feet. Unlike the rest of the figures on the canvas his expression is downcast. He seems to be an outsider.

Cooks isn’t certain if he’s working security or if he’s an off-duty policeman relaxing with the music. But she compared the figure to Jean-Michel Basquiat’s 1981 work “Irony of the Negro Policeman.” “He’s representing law and order and we don’t think about the police being, especially today, friends of the black community,” Cooks said.

Barnes was born into a working-class family in segregated Durham, N.C., in 1938. He painted “The Sugar Shack” from a childhood memory — sneaking into the Durham Armory, a venue that hosted segregated dances and that still exists today. “This was a place where you could go as a black person and see Duke Ellington and see Clyde McPhatter,” Cooks said. Barnes, who died in 2009, recalled in a 2008 interview that the experience was the “first time my innocence met with the sins of dance.”

After being drafted by the Baltimore Colts in 1959, Barnes played professional football for teams including the Denver Broncos and San Diego Chargers until 1965, before pursuing his passion for art.

In the early 1970s, Barnes settled in L.A.’s Fairfax district. He became interested in Jewish culture and was impressed with how much the community knew of its history, Cooks said. “And he really wished that black people had the same type of cultural education.” Inspired by the “Black Is Beautiful” movement, he premiered his exhibition “The Beauty of the Ghetto,” 35 paintings depicting everyday scenes from black life, in 1972.

His work during the time, including “The Sugar Shack,” was about “showing blackness as beautiful and even exaggerating form,” Cooks said. “It’s not about trying to hide the curves of your body or the facial features that you have. It’s about showing them, even exaggerating them and making it not even just OK but something to really be celebrated.”

“The Sugar Shack” ascended into pop culture by chance.

After Barnes played a game of basketball with Gaye, the soul singer caught a glimpse of Barnes’ painting in his car. “He went crazy and he was like I have to have this,” Cooks said.

Barnes augmented the painting to include references to Gaye’s music, and the work became the cover of his “I Want You” album in 1976. That same year, Barnes painted a “Sugar Shack” duplicate, which is on display at CAAM. According to a note written by the artist, he created the second painting because the first “moved around, uninsured” and out of his control.

Most of LACMA’s permanent collection is gone but the entrance price and parking still cost the same, a sad situation for museum-goers and tourists.

In the 1970s, producer Norman Lear commissioned Barnes to create original paintings for the Jimmie Walker character J.J. in “Good Times,” the sitcom about a black family living in a Chicago housing project. In later seasons “The Sugar Shack” was the backdrop for the show’s credits.

The painting became part of American national memory, something of a mythical object, Cooks said. The curator believes Barnes would have found “The Sugar Shack” selfie lines at CAAM to be meaningful.

“It’s wonderful to see how much respect the painting commands,” she said. “People really understand this is a painting that in some ways belongs to everyone.”

'Ernie Barnes: A Retrospective'

Where: California African American Museum, Exposition Park, 600 State Drive, Los Angeles

When: 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesdays-Saturdays, 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Sundays, through Sept. 8.

Admission: Free

Info: https://caamuseum.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.