How will the L.A. Phil carry on amid COVID-19? Dudamel and Smith lay out a plan

“What’s Next” looms large in the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s posters for its 2019-20 season. They are still up at Walt Disney Concert Hall, and they can seem more like a question now that the orchestra on Thursday confirmed the inevitable cancellation of concerts for the rest of the year.

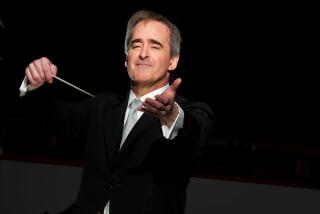

Originally, of course, “What’s Next” was meant as an answer to the question of what could possibly follow the L.A. Phil’s unprecedented, epic centennial season, which confirmed its position as the world’s most artistically venturesome and socially committed major orchestra. But the COVID-19 pandemic turned out to be the answer no one planned for, L.A. Phil Chief Executive Chad Smith said in a Zoom interview in which he was joined by Music and Artistic Director Gustavo Dudamel. They talked about plans they want to be as game-changing as anything else the orchestra has done in recent years.

For the record:

10:26 a.m. July 16, 2020An earlier version of this article said Herbie Hancock will cohost the L.A. Phil series on KCET. He will not. The article also misspelled Beckmen YOLA Center as Beckman.

To the outside world, the L.A. Phil had started to look like it had lost its visionary moxie. While other orchestras immediately began trying to re-create traditional concerts online, the L.A. Phil did very little publicly. Its main effort was a KUSC-FM (91.5) series that began with Dudamel at home and grew to include others in the L.A. Phil family, such as Esa-Pekka Salonen and Yuja Wang.

But Smith and Dudamel said the L.A. Phil was simply being the L.A. Phil, intensely focused on how to use the pandemic to create artistic possibilities.

“Whatever we do right now,” Dudamel said, “has to have an impact not only in the time we are living but also to help us achieve what we can do in the next years. That’s why we were not rushing to do a thousand things, to do this or that. We went to the heart of what transformations we need to make and what we think can work.”

What can work, that is, given that the orchestra is projecting a $90-million loss of revenue this year (vastly more than any other orchestra), largely because of the cancellation of the cash-cow Hollywood Bowl summer season, along with the spring and fall seasons in Disney Hall.

“In the first couple of weeks, my head was underwater just trying to figure out what the financial position of this organization is, and how do we keep the ship afloat,” Smith said. “But at all those moments, Gustavo kept saying that we can’t forget that even at this difficult time, even as we’re struggling to right the ship, we have to keep music at the center of everything.”

First and foremost was YOLA, the Youth Orchestra Los Angeles, for kids who had no access to music education. Dudamel founded it in 2007, just after being named music director. “There is no pandemic, there is no crisis big enough where our commitment to YOLA could waver,” Smith insisted.

Instruction is carrying on for about 1,000 students online. Construction on the Frank Gehry-designed Beckmen YOLA Center in Inglewood is expected to be completed in December and could begin welcoming up to 2,000 kids early next year if COVID-19 has been contained.

“One of the things that has been really beautiful about this,” Dudamel said, “is that there are kids who played in my first concerts who are now in college and are teachers at YOLA. Now they own the institution, and you cannot imagine the conversations, conversations for hours with the kids, about social justice.

“What we found in the middle of this crazy moment, this difficult but important moment, is leaders. They are leaders who have been transformed by YOLA, and the result goes beyond everything that we expected. We were thinking this was an opportunity for them to have access to art, but what we’ve gotten are incredibly eloquent leaders who are challenging us with the kinds of music we play and the vision of the L.A. Philharmonic.”

Coronavirus may have silenced our symphony halls, taking away the essential communal experience of the concert as we know it, but The Times invites you to join us on a different kind of shared journey: a new series on listening.

To that end, Smith described conversations with Dudamel about how to continue to engage with audiences. “You, Gustavo, said everything needs to be for the widest possible audience. And in the early days of COVID-19, you were like, ‘Let’s do a radio show to get people to gather around the radio to re-create that communal experience.’

“Then you said, ‘We need to focus on TV, because people are watching TV. And if we can’t go to the Hollywood Bowl, let’s bring the Hollywood Bowl to people in their living rooms.’”

Beginning Aug. 21 on KCET, “In Concert at the Hollywood Bowl,” produced in collaboration with PBS, will consist of six weekly thematic programs revolving around Latin music, dance, Broadway, jazz or classical works. Each program will compile performances from the Bowl’s video archives. Dudamel will host.

Dudamel said that despite all his work in media, this is a new challenge. (“I’m not a host, but I will be hosting the TV programs.”) Yet for him, it’s all part of the pandemic opening doors for reinvention.

He notes that his mentor, José Antonio Abreu, was “a man of crisis,” and crisis was a daily matter in Venezuela, where Abreu founded El Sistema, the revolutionary music training program that was the inspiration for YOLA.

“And I will tell you something funny,” Dudamel said. “If there was not a crisis, he created one, because a crisis forces you to rise to another level. His philosophy was, ‘Let’s not worry, and let’s try to solve the problems.’

“So for us, nothing has to stop. You have to re-create yourself, do things you have not done. But you also have to do the things you can do, and that means our musicians have to get back and play where it is safe.”

That’s the Hollywood Bowl. The stage is more than twice the size of Disney Hall’s, making social distancing feasible. It’s outdoors, making it far safer than a concert hall. Sophisticated miking already has been set up for recording. The most common word for the setting is “iconic.” It is the ideal for streaming live performances without an audience.

“But if we’re going to do streaming, and we are, we have to do it our way,” Smith said. “This is going to be our biggest experiment, and we’re going to be throwing a lot of spaghetti at the wall.”

Later this month, the L.A. Phil will begin filming performances for a streaming series intended for the phone, the tablet or the computer screen. Dudamel said he wants to invite directors versed in digital media to produce them. And most of all, he said he wants to “send a message.”

Like the PBS broadcasts, they will be thematic programs, with new and old music, and one of Dudamel’s priorities is the streaming continuation of the Power to the People! festival he and Hancock were in the midst of when the orchestra shut down in March. The interruption proved especially frustrating for an orchestra that was already addressing the issues of social justice before they came to galvanize the nation after the killing of George Floyd. Both Dudamel and Smith contend that the festival also had a profound effect on the young YOLA musicians.

Filming with the orchestra should begin before Dudamel leaves in August to conduct the Vienna Philharmonic at Salzburg Festival, an alternate classical music universe where such things can happen. Dudamel expects to travel, but you never know.

For Smith, you never know has become a way of life. “We are rigorous planners,” he said in describing how the L.A. Phil has realized its grand ambitions in the past. “We are really good at laying out the vision and executing against that vision, yet this kind of muscle in this moment is not really what is needed. We have to be flexible. We have to be imagining so many multiple futures, so many multiple possibilities for everything we do.”

In particular, the orchestra has to be imagining how to cope with its enormous financial loss. For that, Smith has cobbled together a budget that includes pulling $20.6 million from the $350-million endowment (on top of the annual $17 million draw), considerable belt tightening with furloughs and 35% pay reductions for orchestra and staff, and fundraising to the tune of $35 million. That will get the institution through the next season.

Spring concerts are up in the air. If they can be resumed, they surely will be highly reduced in number, limited in size and socially distanced.

In the meantime, though, the orchestra will return to radio with broadcasts of archived concerts, and it will release a wealth of commercial recordings of live concerts, including Dudamel’s Ives, Schumann and Dvorák symphony cycles. Beyond that, Smith said, “the only thing I am certain of is that whatever we imagine we’re going to be doing in two months is probably not going to happen. Something else will.”

There is, though, one other certainty for Smith. “If you lose $90 million of revenue, the economic tail of that is long. But for us it’s not existential.

“When I was doing nothing but financially modeling and trying to figure out every possibility, Gustavo said to me, ‘My dear, we’re going to get through this, and we’re going to get through this because we’re the L.A. Phil.’”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.