Review: Tchaikovsky on a grand scale

Orchestras everywhere play a lot of Tchaikovsky. The Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela, its musicians raised on the Russian composer, plays a whole lot of Tchaikovsky, as it has been doing this week in the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s Tchaikovsky-Fest. “Playing” is maybe what these still-young musicians (17 to 31) did when they were children in El Sistema, Venezuela’s nationwide music education program.

But what this robustly massive ensemble did to three symphonies and three Shakespearean symphonic poems in concerts on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday at Walt Disney Concert Hall and the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels was to devour and subsume Tchaikovsky as if his music contained restorative nutrients necessary to change the world.

The Russian composer was a grandiose depressive notable for amplifying self-obsession into stirring symphonic art on an unprecedented scale. When more than 200 Bolívars, led by Gustavo Dudamel, cram onto the Disney stage, they too operate on an unprecedented symphonic scale, with typically double the normal contingent of brass, winds and strings. With spectacular unity, they give the impression of moving and breathing as a single organism, making every phrase a living thing.

PHOTOS: Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela plays Tchaikovsky

These musicians exhibit a conviction that takes no prisoners. At the opening of the Fourth Symphony on Monday, Dudamel detonated eight horns for a Tchaikovsky meant to express fate, and a listener felt fate in all its inescapable mercilessness. When Dudamel unleashed the black ferocity of Tchaikovsky’s “Hamlet” on Wednesday, there was no “To be or not to be.” There was only to be.

Fate for this orchestra means one thing: the fate of Venezuela. The Bolívars come to L.A. in a troubled time, with demonstrations on the streets of their country and reports of violence. Theirs is a divided country that appears dysfunctional. The current Socialist government has become repressive. The opposition has ties to big business, and the rich in Venezuela protect themselves from the poor. There are shortages of essential goods, skyrocketing inflation and a shocking murder rate. People don’t know where to turn.

Still, the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra is a source of Venezuelan pride (maybe the only one) that crosses all social, economic and political divides. It stands for what Venezuela can be. Its players, many who grew up together playing music, represent the Venezuelan variety yet function as one. You hear them play, and you understand where the leaders who can renew a great nation might emerge.

RELATED: Orlando Bloom, Joe Morton brighten TchaikovskyFest at Disney Hall

When appointed music director of the L.A. Phil seven years ago, Dudamel inspired an El Sistema-type program for YOLA, Youth Orchestra LA. The first time he conducted a group of children in South Los Angeles, most had had instruments in their hands a short while.

Tuesday evening, members of YOLA sat side by side with players from the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra at the cathedral for Tchaikovsky’s Second Symphony (“Little Russian”) under YOLA’s conductor, Bruce Anthony Kiesling. Tchaikovsky was, in his early symphonies, still in high spirits, and the performance captured them.

Dudamel’s symphony program at Disney the night before was of the next two Tchaikovsky symphonies. The Third is called “Polish” but, like everything Tchaikovsky wrote, sounds 100% Russian. It is the Tchaikovsky of dance. The Bolívars are dancers, and they made the “Polish” sparkle. The scene was set for fate to enter the room.

The Fourth is Tchaikovsky in emotional crisis. Dudamel has conducted it with the L.A. Philharmonic, but with the Bolívars the scale changes, the physicality increases, the intensity grows. Dudamel treated the Finale as abbreviated triumph, revealing a goal rather than the reaching of it.

PHOTOS: Disney Hall conductors

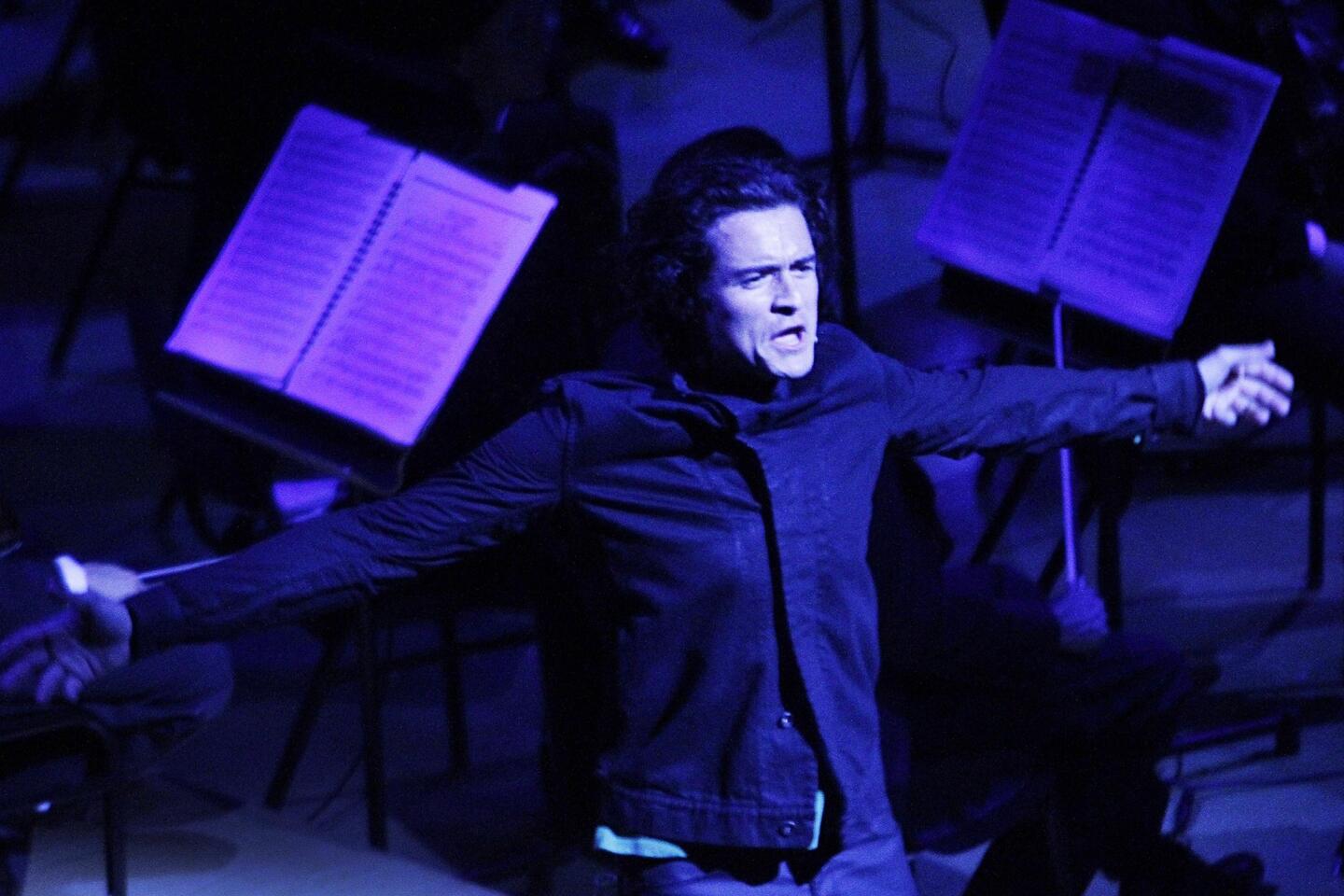

Wednesday night’s Bolívar program of Tchaikovsky’s “Hamlet,” “The Tempest” and “Romeo and Juliet,” with interludes of scenes from the plays staged by Kate Burton, was a repeat of an event that Dudamel presented with the L.A. Phil in 2011. Robert Sean Leonard was Hamlet in the organ loft. Joe Morton proclaimed Prospero in front of the orchestra. Orlando Bloom was an athletic Romeo running around the hall. Condola Rashad was Juliet and her balcony, an orchestra terrace.

The Hamlet and Prospero speeches were irrelevant to Tchaikovsky’s personalized, Russianized Shakespeare. Romeo and Juliet were more suitable, but the whole thing failed because amplification was terrible, actors thinking too much of themselves to tone it down so Shakespeare’s text could be conveyed.

The orchestral performances were, on the other hand, mighty in their pointed intensity. Shakespeare, filtered through exaggerated Russian sentiment, was turned into Venezuelan ambition of collective action. Here, clearly, is the future. The TchaikovskyFest has brought demands from protesters that Dudamel and the L.A. Phil become involved in Venezuela’s politics. But what about us?

Wednesday, KPCC reported that the Los Angeles Unified School District wants to cut the elementary orchestra programs in half. I guess that means one place where there won’t be a lot of Tchaikovsky or new leaders.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.