Review: Six opera works-in-progress, all terrific, from the Industry

Opera, in our parts, has embarked upon an exceptional period of expansion. Up and down the California coast, the staging of new and recent work possibly outnumbers old.

This year, moving from south to north, UC San Diego in La Jolla has had two major world premieres; Long Beach Opera has given us three regional or U.S. premieres; Santa Monica’s Broad Stage is offering the world premiere of Lee Holdridge’s “Dolce Rosa”; the Los Angeles Philharmonic has staged John Adams’ “The Gospel According to the Other Mary”; Stanford University has already produced new operatic work in Bing Concert Hall, which opened only in January; and San Francisco Opera is presenting the world premiere of Mark Adamo’s “The Gospel of Mary Magdalene” the week after next.

Now add six more new operas to the list, thanks to First Take at the Hammer Museum on Saturday afternoon. This is only the second project of the Industry, the young L.A. company devoted to experimental opera, which last year debuted with Anne LeBaron’s “Crescent City” and is quickly and dramatically making itself an essential component in American opera.

PHOTOS: L.A. Opera through the years

First Take takes its impetus from New York City Opera’s program of workshopping new operas, which the Industry’s founder and artistic director, Yuval Sharon, ran for four years last decade. An open invitation went out to composers and librettists, and more than 50 works were submitted. Each of the six selected received a concert performance of excerpts in the Hammer’s Billy Wilder Theater, with a touch of video and in some instances, a touch of stagecraft.

The instrumentalists were drawn from wild Up. The Industry’s music director, Marc Lowenstein, and wild Up’s music director, Christopher Rountree, shared the conducting duties. The singers were mostly young. Performances were uniformly terrific.

No one opera resembles another in musical or literary style or even theatrical intention. And two, as different as night and day, promise great things. Mohammed Fairouz’s “Pierrot” is an art-song cabaret trespassing as opera by a remarkably prolific New York-based composer born in 1985. At the opposite extreme, Pauline Oliveros’ “The Nubian Word for Flower” is what the composer calls a “phantom opera” and is by a famously transcendent experimentalist who celebrated her 81st birthday Friday.

“Pierrot,” written for the extravagantly transgressive tenor Timur Bekbosunov, is a setting of 10 drunkenly hallucinatory texts by another irresistible extravagant, the cultural critic and poet Wayne Koestenbaum.

“I like Wayne,” Fairouz said in a video introduction, “because he’s highbrow enough for my tastes. But he’s quite dirty.”

Fairouz and Koestenbaum pay crazy homage to the centenary this year of Schoenberg’s “Pierrot Lunaire,” which (as with Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring”) also just turned 100. The ensemble of flute, clarinet, violin and piano is the same that Schoenberg used, and it was nice to have six numbers premiered from Fairouz’s “Pierrot” barely more than three miles from where Schoenberg lived in Brentwood.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture by The Times

Of course, this is Schoenberg in company with Virginia Woolf in a funny detox clinic lobby where liquid runs down her leg, perhaps schmaltz. This is Schoenberg as transcribed by Liberace and Edward Said as Yiddishkeit. The score is sweet and sour, sophisticated and screwy, sentimental and angry, and oddly spiritual for being able to incorporate all the above.

Bekbosunov was born to be this 21st-century “Pierrot,” brilliantly animating every note, expression and transgression.

Oliveros, a pioneer in electronic music and a practitioner in what she has termed “deep listening,” goes deep in “The Nubian Word.” The concept, story and texts are by Ione, who examines the colonial mind through a mystical vision of British Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener, who mapped the Middle East at the end of the 19th century. We encounter him on a Nubian island.

Oliveros begins with an extraordinary cosmic electronic soundscape, traveling aurally from outer space to desert, ocean and meadow, where each flower finds its own electromagnetic field. An instrumental ensemble improvises subtly around and inside the electronics, while four singers provide the surface drama.

“Remember,” one says, “Heaven in your language is not the same as in mine.”

Oliveros’ musical language, formed over a long lifetime of deep listening, is not the same as anyone else’s. Here it is distilled in the vastness and fearless intensity of tone.

Two other works were sonically imaginative. Icelandic composer Davíd Brynjar Franzson’s “longitude” is also colonial and landscape-driven. But where Oliveros is deep, Franzson intentionally employs surface sounds, the slight scrapping and purling of instruments, for a piece that is also part installation art and all mood. His collaborators are Halldór Úlfarsson, Angela Rawlings and Davyde Wachell.

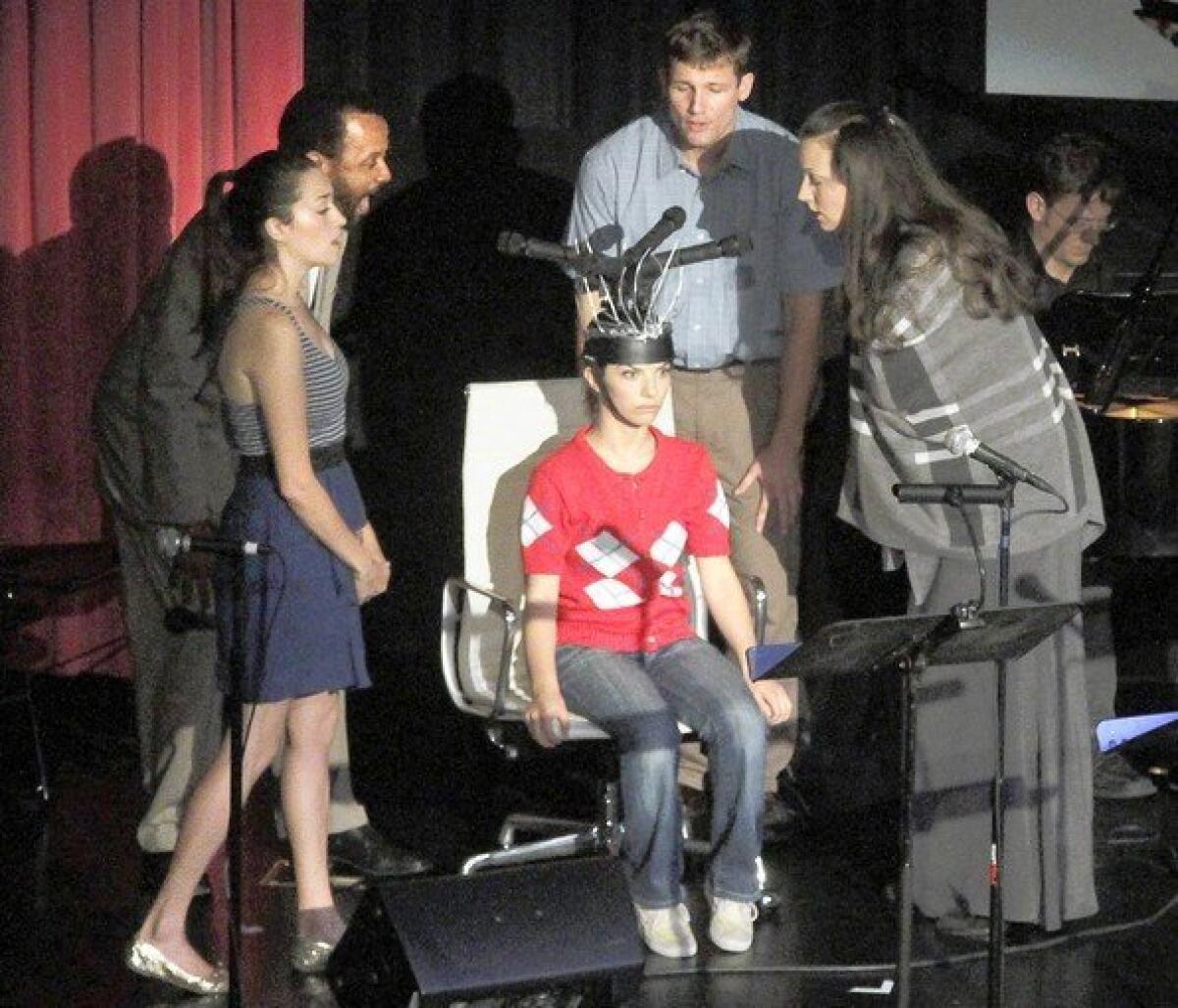

Alexander Vassos’ “The House Is Open” is about a young boy, Charlie (vividly sung by Ariel Downs), who spent much of his youth asleep. His awakening is also a sexual one. Vassos includes a great invention, Charlie’s crown of microphones. As characters revolve onstage, their amplified voices do too.

Aaron Siegel’s “brother brother” involves the Wright brothers and a shadowy pair of fictional brothers. The music moves with effectively studied uneasiness between sung and spoken passages.

Ellen Reid’s “Winter’s Child” is meant to be opera as Southern gothic, fixing on a child in an unnatural landscape. There are supernatural doings. Sisters die young. Mama clings. The moody music clings too.

First Take could be the start of something big. All the opera excerpts were recorded, allowing the composers to shop around their works-in-progress. Some will surely see the light. And smartly, the company, now indispensable to the L.A. opera scene, used the event Saturday to announce details of its next one. Christopher Cerrone’s “Invisible Cities” will be given its premiere Oct. 19 at Union Station, with the audience as participants in the action.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.