Review: With ‘Turn of the Screw,’ Pacific Opera Project gets serious

Pacific Opera Project, a young company headed by young artists, calls itself POP and operates on the pleasure principle.

It presents chamber versions of comic opera and operetta in clubs and calls them POP-Up productions. Tables for four cost but $100, with a bottle of wine and snacks thrown in. The atmosphere is casual. The singers are in your face. Everyone is in it together in an effort to make opera fun.

Now, though, POP has gotten serious. For its 10th production and first non-comic opera, the company has turned to Benjamin Britten’s “The Turn of the Screw,” which opened Saturday night and runs through this weekend.

CRITICS’ PICKS: What to watch, where to go, what to eat

The venue is still offbeat. The Rosenthal Theater at Inner-City Arts is on Kohler Street in the arts district of downtown L.A., an area that is deserted in the evenings, helping convey a suitably creepy atmosphere for Britten’s haunted masterpiece based on the Henry James ghost story.

But Inner-City Arts isn’t really all that out-of-the-way. Dinner at a fancy restaurant is five minutes away. And the Rosenthal space is a perfectly pleasant black box theater that seats 140.

Nor is POP’s “Screw” all that offbeat. For its most ambitious offering, POP is not taking big chances. It has assembled a strong cast of emerging conventional opera singers.

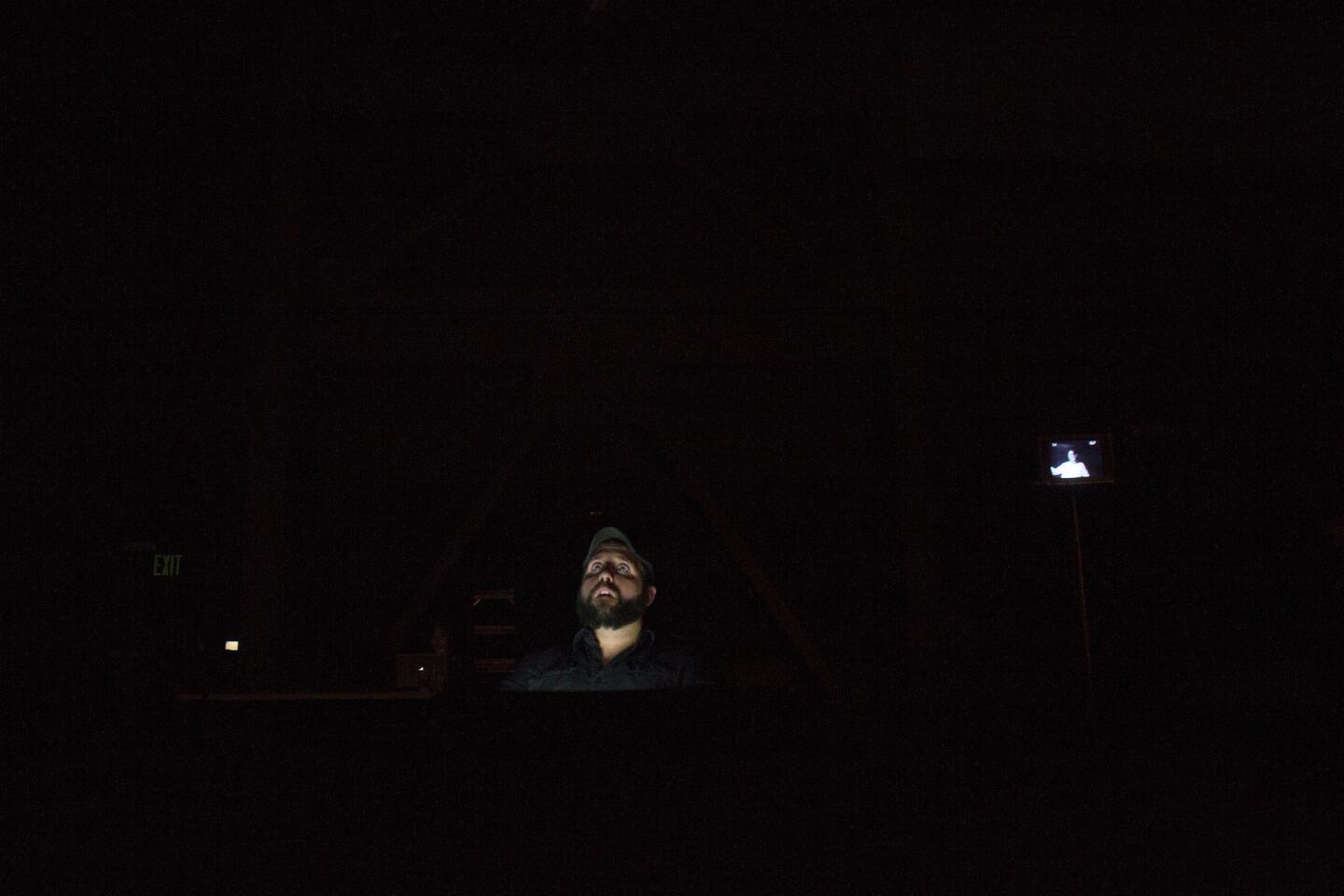

Britten wrote “Screw” as a chamber opera, with an orchestra of 13. I recognized few names in the ensemble — expertly conducted by one of the company’s founders, Stephen Karr — but the playing proved excellent. Josh Shaw, POP’s artistic director and its other founder, was responsible for a narratively straightforward and traditionally well-acted production.

What is different is the level of intimacy. Opera on a conventional proscenium, even when the venue is far smaller than the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion or nearly 4,000-seat Metropolitan Opera, is an art form of deceits. Oversized passion on stage is projected at a distance, and that distance protects an audience from direct exposure to emotive excess. The squeamish are afforded space to psychically remove themselves when need be.

But forget all that in Rosenthal, where the singers and musicians are within spitting distance. They’re aiming directly at you.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

Whether it is that audiences are getting braver or less imaginative, immersion is becoming the new norm in opera. Opera is now commonly consumed on home video and in movie theaters. Close-ups are taken for granted. The elite section at the Chandler used to be upstairs in the Founder Circle, where the view is panoramic and the sound well balanced. Now the hot seats are front row of the orchestra, as close to the stage and the pit as possible.

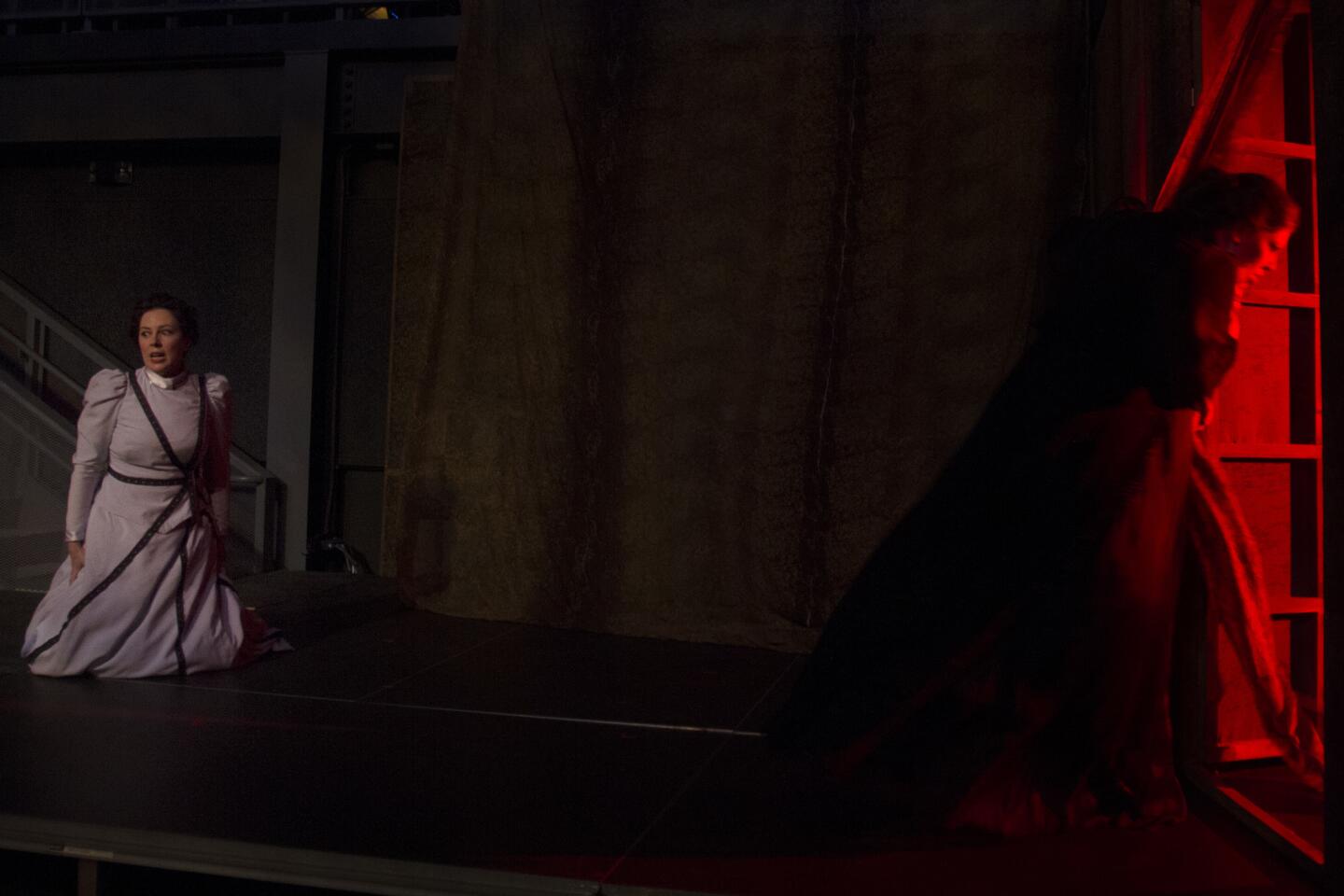

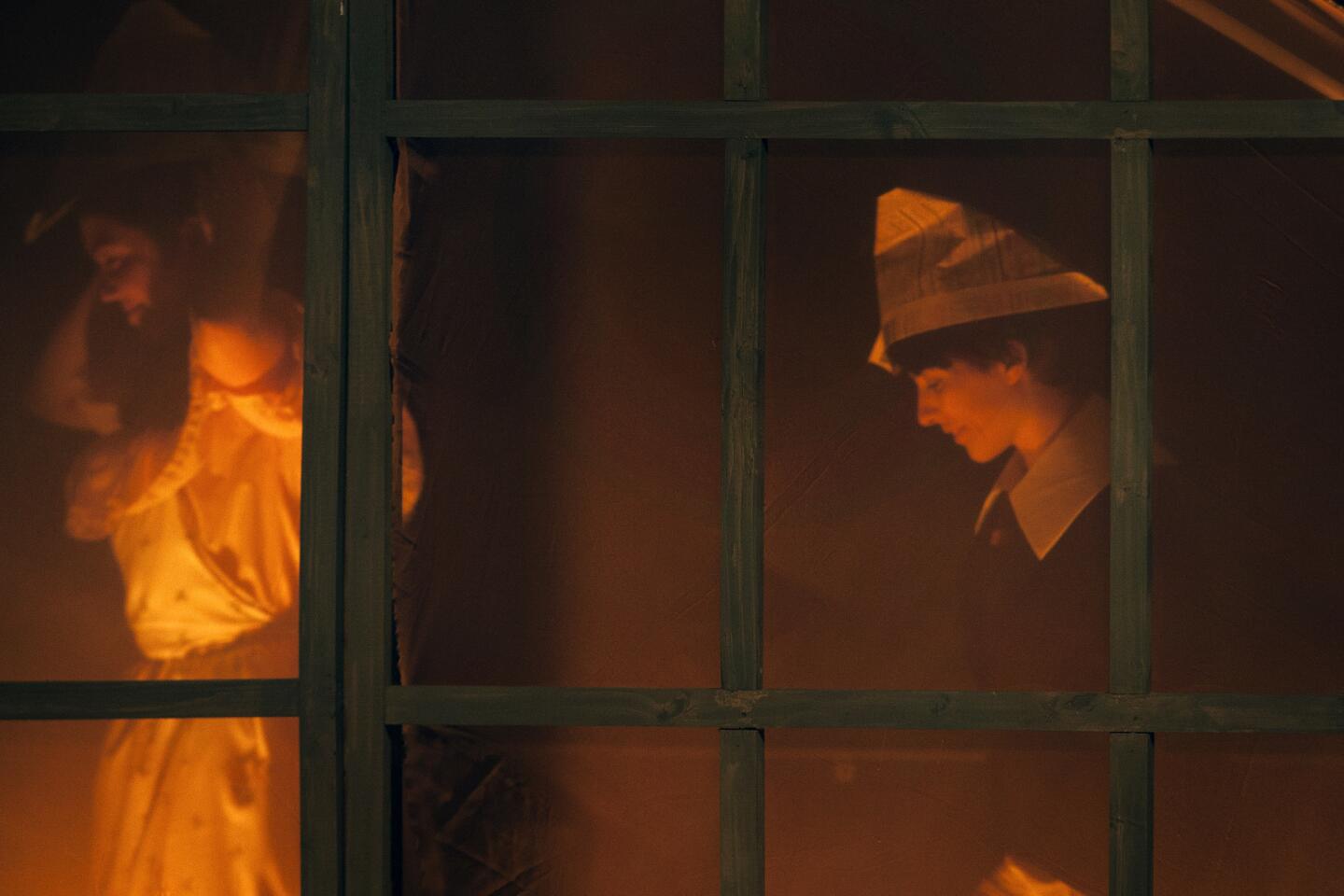

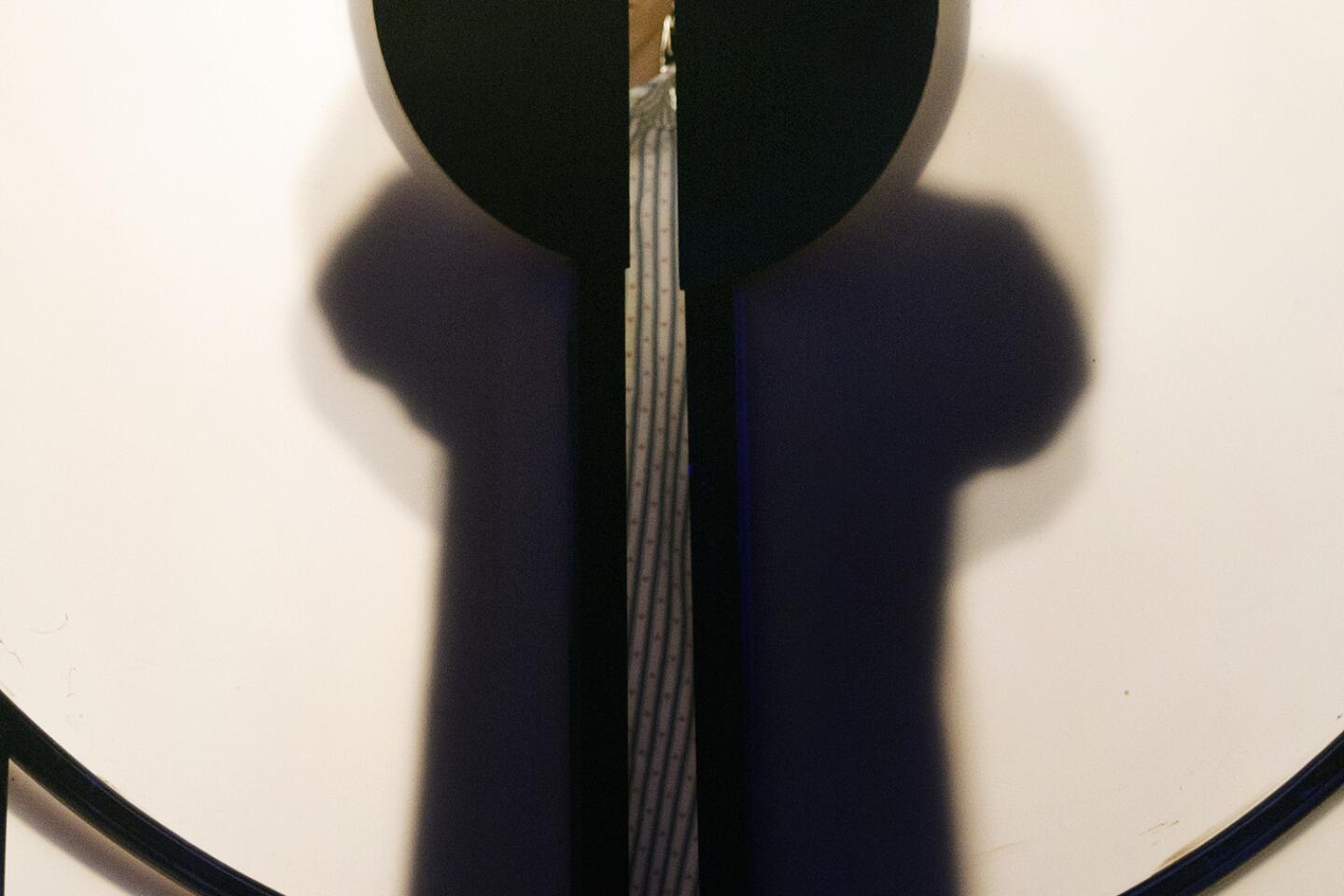

For his “Screw” production, Shaw, who also designed the split-level set, used as much of the space as he could, front and sides. The orchestra was placed on a loft above the stage, conductor communicating with the singers via video monitors in the rear of the hall. The setting was period, as were Maggie Green’s costumes, although the ghosts had an amusing Halloween aura (makeup matters in these close quarters). Ryan Shull added life with vibrantly effective lighting.

There are many interpretive levels to Britten’s opera, in which a new, inexperienced governess and two children lose their innocence in spine-chilling ways thanks to the otherworldly influence of the spirit of Peter Quint, the family’s former manservant. There is a lot percolating under the surface, especially sexually. Shaw’s prim production played it safe, although had he not, he could have created quite a stir, given the intimacy of the setting.

In fact, this “Screw” proved almost too operatic in the old-fashioned sense of the term. As though projecting in big halls, the singers applied generous vibrato and rolled their R’s as a kind of vocal armor. Words were not often clearly enunciated (there are neither subtitles nor a plot synopsis, so bone up on the libretto beforehand). Still, an appropriately alarming immediacy could not be avoided in this space, especially in the quieter, scarier passages.

Intimacy also meant inescapable walls of vocal power. The spooking of soprano Rebecca Sjöwall’s Governess was especially ripe in these claustrophobic surroundings. Clay Hilley’s ghoulish Quint was too close for comfort, which was a good thing. Jennifer Wallace’s Mrs. Grose, the housekeeper, filled the small room with opulence. Marina Harris as the other ghost, Miss Jessel, and the children, Miles (Ariel Downs) and Flora (Katy Tang), took to haunting and being haunted like ducks to water.

Opera, POP this time proved, needn’t always be fun.

“The Turn of the Screw”

Where: Rosenthal Theater at Inner-City Arts, 720 Kohler St., Los Angeles

When: 8 p.m. Fri. and Sat., 3 p.m. Sun.

Tickets: $20 to $35

Contact: (323) 739-6122 or https://www.pacificoperaproject.com

Running time: 2 hours, 8 minutes

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.