Bruce Wagner continues his Hollywood topography in ‘Maps to the Stars’

He stands in black boots and black coat, phone at his ear, as if conspiring with a distant demon. He beckons in a rooftop cafe and hangs up. The Hollywood Hills, which he has known since childhood, rise tidy and neat; houses shine, pools glimmer. But to him, the world beyond the artifice of fame and wealth is depraved and neurotic, spooked by age and petulant with insecurity, narcissism and blind ambition.

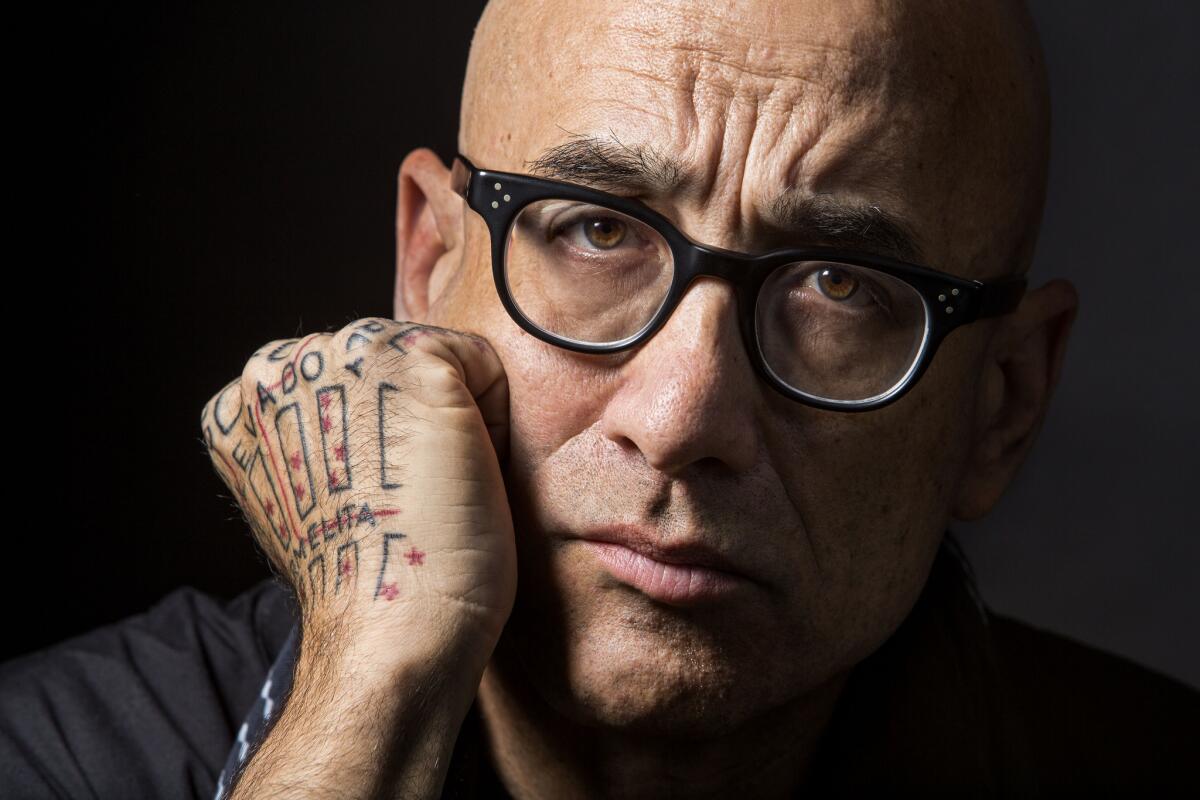

Ambulance-driver-turned-novelist Bruce Wagner, a man of tattooed fingers and wild prose, knows precisely where the hobgoblin of his creativity resides: “Failure and anguish,” he says, an e-cigarette skimming his lips. “I feel those are truly golden doors through which … one becomes a kind of pilgrim in a great cathedral” where the “full force of one’s insignificance” is laid bare.

His novels, such as “Dead Stars” and “The Chrysanthemum Palace,” have excoriated Hollywood’s attention-craving shark tank of talk-show confessions, egos, greed, disease, antidepressants, pornography, squandered fortunes and movie star death watches. At his best, Wagner, who dropped out of Beverly Hills High School when he was 16, is a word magician of mischievous glee, a conjurer of imaginary prisons and insatiable appetites.

“Hollywood is a laboratory for need and vanity,” he says. “The knives are always out, and I’m often holding them.”

His predilection for lurid rhythms, including a drug-crazed paparazzo on the prowl for celebrity crotch shots, has drawn comparisons to other chroniclers of Hollywood’s darker impulses, notably F. Scott Fitzgerald and Nathanael West. But Wagner, whose bar mitzvah was in the bygone Friars Club, writes from the inside. His overlaying story lines, societal insights and thickets of characters evoke Dickens, while his bawdy sense of language is reminiscent of Henry Miller. Wagner, though, is his own creation, a writer of propulsive voice; fierce and scathing, but also tender as a hymn to soothe a “fractured sense of self.”

To find him, follow Sunset Boulevard to West Hollywood. Park and hop on an elevator. Morning clouds burn away, life below skates quietly past. Wagner smiles and removes the black coat, revealing a zip-up blue jumpsuit. He resembles a car mechanic who has stumbled upon a watering hole for the literati, in this case the Soho House, an airy haunt of whispers and leather chairs, where a few patrons appear to be concocting fiction or perhaps a memoir or two. It’s studious and bohemian at once and, if he hasn’t done so already, Wagner, 60, could lampoon the atmosphere in a novel.

Bald with an angular face peering from behind thick, black-framed glasses, Wagner has “Rodeo,” “Roxbury” and other Beverly Hills street names tattooed on his fingers, as if the body is both canvas and map. Critics, who are often exasperated and excited by his narrative outlandishness, tend to refer to him as a high-octane satirist. He dismisses the notion, suggesting his work is a true reflection of Hollywood’s demented, self-inflated empire, where dilettantes, producers, stars and agents shape a culture tuned to vacuous self-reflection and riven with Twitter-speak that flits like water bugs across screens large and small.

“People go a little bit insane when it comes to anything written about Hollywood,” he says. “Critics that often set the tone for discourse go mad and feel that if one is writing about Hollywood, one must be attempting with success or not to expose the idiocy and malignancy that are rampant here.” He added that he is preoccupied “not just with fame but with anonymity and not just with an excess of wealth but also with extreme poverty, both financial and of the spirit.”

That mood permeates Wagner’s screenplay for “Maps to the Stars.” Directed by David Cronenberg and starring Julianne Moore and John Cusack, the film, expected to open this autumn in Los Angeles, is a dive into perversion, faux spirituality and familial sins. Similar themes gird Wagner’s novels, including “The Chrysanthemum Palace,” a 2006 PEN/Faulkner finalist that explores the addictions and insecurities haunting the children of celebrities.

“Bruce is like James Joyce with ‘Ulysses,’” says Cronenberg, who has known Wagner for years. “He’s unafraid to express the moment … to go to the darkest places. Hollywood is his Dublin.” He adds that Wagner, who went to the Cannes Film Festival in May for the premiere of “Maps,” which was 20 years in the writing and faced financing hurdles, was “a kind of star on the red carpet. He’s not a typical writer. He’s comfortable with cameras and microphones.”

Cronenberg laughs and notes that Wagner stood out in the French resort. “He could definitely play a thug in a movie. A sensitive thug. He was at Cannes and he wore a hoodie.”

Wagner’s preferred method of communication seems to be email. He responds quickly and sometimes signs off with “Anon.” There’s an air of mystery about him, but when one finally meets the author he’s engaging and talkative; his voice has a late-night radio timbre, and his eyes possess a sly gleam.

“Every time you have a conversation with Bruce, it’s the most amusing time of the day,” says Sarah Hochman, his editor at Blue Rider Press. “I put him right at the top pantheon of really insightful Americans writing today.... He has an extraordinary sense of justice, of cosmic justice.”

Wagner’s most audacious work is “Dead Stars,” a 600-plus-page novel written after he detoxed from prescription drugs about four years ago. Among its many obstinate, scarred and copulating characters are a 13-year-old breast cancer survivor worried she may be upstaged by a 4-year-old who just had a mastectomy, and Jerzy Shores (the author has a flair for names), a paparazzo who tracks the failing health of stars on https://www.deathlist.net. In one passage, which reveals Wagner’s deftness at drawing moments of compassion from cruelty, Shores stalks a cancer-weakened Farrah Fawcett days before her death.

“She startled for a moment, her instincts not knowing if he was an assailant — friend or foe — but when she saw his camera, she unmistakably Farrah-smiled, there was relief, not foe but friend, he was part of her tribe.... And that was when it happened: every showbiz cell in her body bade her smile, graciously and valiantly, even during a rape such as this, & at the very end the swimsuitfamous smile collapsed into a tender rictus belonging to one already launched into oncoming oblivion.”

The New York Times critic Michiko Kakutani, who has often praised Wagner’s work, panned “Dead Stars,” saying: “Aside from a few bravura scenes here and there, this self-conscious, tricked-up volume consists largely of gruesome anecdotes — which feel contrived for maximum gross-out value — desultorily strung together like ugly beads on a filthy string.... This novel feels more like a weary wallow in Hollywood scum than the sort of savage satire this gifted author is capable of writing.”

Sam Sacks in the Wall Street Journal noted Wagner’s salacious riffs but said: “If the book were just this — virtuoso screed and unsparing parodies of frauds and fame-whores — it would be enjoyable as a piece of provocation and nothing else. But Mr. Wagner’s showstopping trick is to introduce his repellent cast of characters warts and all (often warts and nothing else) and then, subtly and convincingly, make you care about them.”

Wagner is accustomed to divisiveness regarding his novels; one senses it gives him a sense of equanimity, like the bubble floating in a carpenter’s level. Negative and positive reviews, he says, “are helpful in reminding one that all is vanity. All is fleeting.” And, then, almost as an afterthought, his voice drops a key: “My work is not very accessible. My work is not friendly, I believe.”

A personal darkness

Friend and novelist Jonathan Lethem got to know Wagner through “that classic Wagnerian thing: the movie that was never going to be made.” Wagner was adapting Lethem’s 1997 novel, “As She Climbed Across the Table,” for the screen, but the project fell through. “I’ve been a fan since I was a bookseller in Berkeley,” Lethem said of Wagner. “I find his work hypnotic, the combination of his worldliness and his totally wide-open heart.”

Lethem later ended up cameoed in “The Chrysanthemum Palace.” Wagner placed “me at a funeral for a famous writer,” said Lethem, who was a bit taken aback. “You feel weirdly threatened or appropriated. Why am I there? I returned the favor in my novel ‘You Don’t Love Me Yet.’ I put Bruce in a crowd scene.”

The son of a producer-turned-stockbroker, Wagner was born in Wisconsin and grew up in Beverly Hills. “Gilligan’s Island” star Tina Louise was a guest at his bar mitzvah. He was friends “with the children of the famous, an impossible burden I always felt; [they are] buried alive, in essence.” After dropping out of high school — “I couldn’t see where that was going” — he worked in bookstores, including Campbell’s in Westwood, and wrote scripts and stories for films, among them “Scenes From the Class Struggle in Beverly Hills” and “A Nightmare on Elm Street 3.”

He says by 30 he was “deeply unsatisfied” and turned more toward writing prose. He read Fitzgerald’s Pat Hobby stories about an alcoholic screenwriter. “I wanted to go much further than Fitzgerald had gone,” he says, “[His] stories were written for money at the end of his life. They were kind of howls.... But I wanted to explore the personal darkness that was mine.”

Such darkness could be glimpsed careening through town with the rich and the wounded. “Driving a limousine was very similar to driving an ambulance. You had people in extremis,” says Wagner, who appears briefly as a chauffeur in “Maps to the Stars” and whose 1991 debut novel, “Force Majeure,” follows the sordid life of screenwriter/limo driver Bud Wiggins. “You had people who were extremely famous: Olivia de Havilland, Mick Jagger. You had people renting limos to appear to be famous.”

Behind the wheel of an ambulance, Wagner, once married to actress Rebecca De Mornay, picked up vagrants along roads and railways, including people with “gaping bedsores filled with maggots. We’d bring them to county general and nurses would pour buckets of kerosene into their open wounds to kill the maggots … I was in morgues for the first time and saw the dead. An epic event for me to see the dead. The body desecrated by pathologists.”

His mother, who worked for decades at Saks Fifth Avenue, died in her sleep at home not long ago. She was 88 and had dementia. “It was a tidy end … she had a good death … not a blossoming black-and-blue mark on her from being manhandled by emergency room care workers.”

Death and spirituality, notably Buddhism, infuse much of his writing. He is not a Buddhist but is intimate with its teachings and the smugness in which the West’s affluent often embrace the religion. His new novellas in “The Empty Chair” include a Buddhist living in Big Sur. “My books,” he says, “have always had a spiritual component to them … without transcendence you have a closed set.” Kit Lightfoot, a movie star in “Still Holding,” a novel from 2003, is a practicing Buddhist depicted thus: “He loved having blundered into this magisterially abstract Shangri-la of the spirit, a flawless diamond-pointed world that might liberate him from the bonds of narcissism, the bonds of self.”

Wagner exudes the fascination of a Hollywood blogger trolling for dirt. His novels drop more names than a publicist — BlackBerry aglow — tilted against an open bar during awards season. In “Dead Stars,” Michael Douglas undergoes chemo/radiation and maneuvers to remake Bob Fosse’s “All That Jazz” while Catherine Zeta-Jones guest stars on “Glee.” Celebrities in “Still Holding,” such as Drew Barrymore and Russell Crowe, must contend with look-alikes rented out to parties in their stead. It all simmers in a scabrous stew of news, gossip and titillation where the gold-plated famous mingle, sin and cajole with their wannabe lessers.

Hollywood then and now

The culture and antics of Hollywood have remained rather constant over the years but, he says, the money is different. “I really look at change in Hollywood not artistically [but in] what has changed financially.” He adds: “You’re shocked to learn that a movie has made $1 billion and you find out that most of the profit was made in Europe or China” or other countries.

His haunts have also changed over time, except for a few, such as Versailles, a Cuban restaurant where he used to eat with writer and shaman Carlos Castaneda. When he’s depressed, he says, one might find him with “Carl’s Jr. / KFC box lunches eaten in car at random beach parking lots.”

It’s pushing noon. The Soho House is filling up. The hills are bright, fake almost, like the collision of a cartoon and the real world. “You enter the dream that was created for you,” he says. Soon, Wagner, his black coat draped over a chair, will descend his perch and disappear, likely responding to emails and checking the latest grist from the town he’s fluent in. He’s reached that point in life where art is more intimate and craft intensely personal.

“You write for the sheer joy of it,” he says. “The way a runner runs or the way a musician plays. You’re no longer writing for the critics. You’re no longer writing even for the readers” — he smiles —”perhaps my great flaw.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.