Do you need to remember music to enjoy it? Do you need to recognize it?

Since 1987, Autechre’s Sean Booth and Rob Brown have been reorganizing, hearing and unhearing electronic music on our behalf. The roll call of people who borrow from them is almost pointlessly long. Did your favorite live band get squelchy and clicky in the aughts? Autechre. Were you mad when Radiohead abandoned verse-chorus-verse guitar rock to make those mongrel striations they’ve been releasing for over a decade? Autechre. If you encounter otherworldly music built from machine-generated noises, it owes Autechre a Christmas card.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines >>

On Nov. 1, after no promotional push, Autechre launched a page on Bleep, the Web store of its English label Warp. The only thing available so far is “Ae_Live,” a collection of four, hour-long live shows recorded in Europe during the last four months of 2014. (If you’re comfortable listening to MP3s, the set will cost you $12.50; audiophiles can get 24-bit WAV files for $23.)

Is “Ae_Live” an album? Maybe. During several weeks of communicating with Booth before and after Autechre’s L.A. appearance at the Fonda on Oct. 15, I asked Booth if a new album was coming. “Depends on how you define an album,” was his answer. Frustrated, I suspected “Ae_Live” was the other shoe of his answer, and it was. “These shows were intended for release, provided the recordings worked OK,” Booth clarified. “The performances were good enough.”

How long does it take to absorb four hours of music? If you’re listening to Autechre, that answer involves a much larger number than if, say, AC/DC was the test case. Autechre’s music was already subtle and odd when they started releasing records in the early ‘90s, caught mistakenly in a wave of “ambient” electronica they had little interest in.

“There was a big culture of taking acid and staying in at the time, instead of doing E and going out,” Booth said. “We were more into that, hanging out and getting weird, hearing the way weird things sounded weird. We were doing stupid stuff like plugging a TV into an effects unit and then running it off a drum machine and watching telly.”

Autechre’s early tracks contained enough gentle moment for Warp’s late co-owner Rob Mitchell to push them toward the growing non-dance ambient dance genre on their first album, “Incunabula.” After that, the duo rejected outside advice and started releasing the tracks indebted to the hip-hop and sound effects they grew up loving.

When they were still using drum machines and keyboards and samplers, they were able to create rebarbative clots of noise that sounded as if they were trying to drive you out of your own home. (The ecstatic drill-press stomp of “Second Bad Vilbel” from the 1995 “Anvil Vapre” EP is a good example.)

Then, the growth of software synthesis programs in the ‘90s and aughts changed Autechre’s sound, and upped their ability to avoid known grids easily followed. This is where the necessary listening time doubles and trebles. “Second Bad Vilbel” is abrasive, full of microscopic and almost inaudible detail, but it still moves in a variation of 4/4, at a recognizable tempo.

The music on “Ae_Live” rarely does anything that obvious. If you go to the four-minute mark in their Utrecht performance from Nov. 22, 2014, you’ll hear whooshes, honking tones and the reflection of irregularly spaced notes. The only thing that repeats in a time signature is a low sound that resembles a kick drum. That disappears before the six-minute mark, when a passage of what could be someone hitting exposed piano strings begins. Less than a minute elapses, then the muffled timekeeping returns, slower. In almost every other kind of pop-derived music, events return in roughly the same relationship to other events, at constant intervals, even if those intervals counted out in an odd meter. Autechre inserts so many different lengths of time between sounds that a listener could be forgiven for thinking she’s just hearing a stream of improvised electronic noise.

Several weeks spent listening to the live sets, though, made it clear that each set dealt with much of the same information: that piano string section (seventh minute in Utrecht, eighth minute in Dublin); a buzzing bass line that approaches melody; a bright, horn-like sound being chopped into flickers with a thin drum sound; and a watery stretch of what might have once come out of a hammer dulcimer. The software Autechre uses most often now is called Max/MSP, a programming interface used by musicians, artists who specialize in sound installations, and anyone who needs to synchronize many sounds in time and, sometimes, space. For the last six years, Brown has been living in Bristol, and Booth has been in Manchester. Exchanging Max files over the Internet hasn’t slowed them down. “I’m programming a lot of the time, and then we’re kind of hacking each other’s stuff,” Booth said. “It’s a deeper kind of collaboration really, despite the distance.”

If you saw one of the 18 American dates, which took place mostly in October, you heard something even more decentered than what you can hear on “Ae_Live.” The duo was especially fond of their L.A. date. “It was really good,” Booth said. “The crowd seemed to enjoy the same bits we did.”

1/82

Madonna performs at the Forum in Inglewood on Oct. 27, 2015. Read the review.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times) 2/82

Don Henley performs at the Forum in Inglewood on Oct. 9, 2015. Read the review.

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times) 3/82

Los Lobos perform at El Gallo Plaza in East Los Angeles on Sept. 29, 2015. Read the review.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times) 4/82

Silversun Pickups perform at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery Masonic Lodge on Sept. 28, 2015. Read the review.

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 5/82

R. Kelly, cigar and mike in hand, performs at the Forum in Inglewood on Oct. 10. Read the Times review.

(Axel Koester / For the Los Angeles Times) 6/82

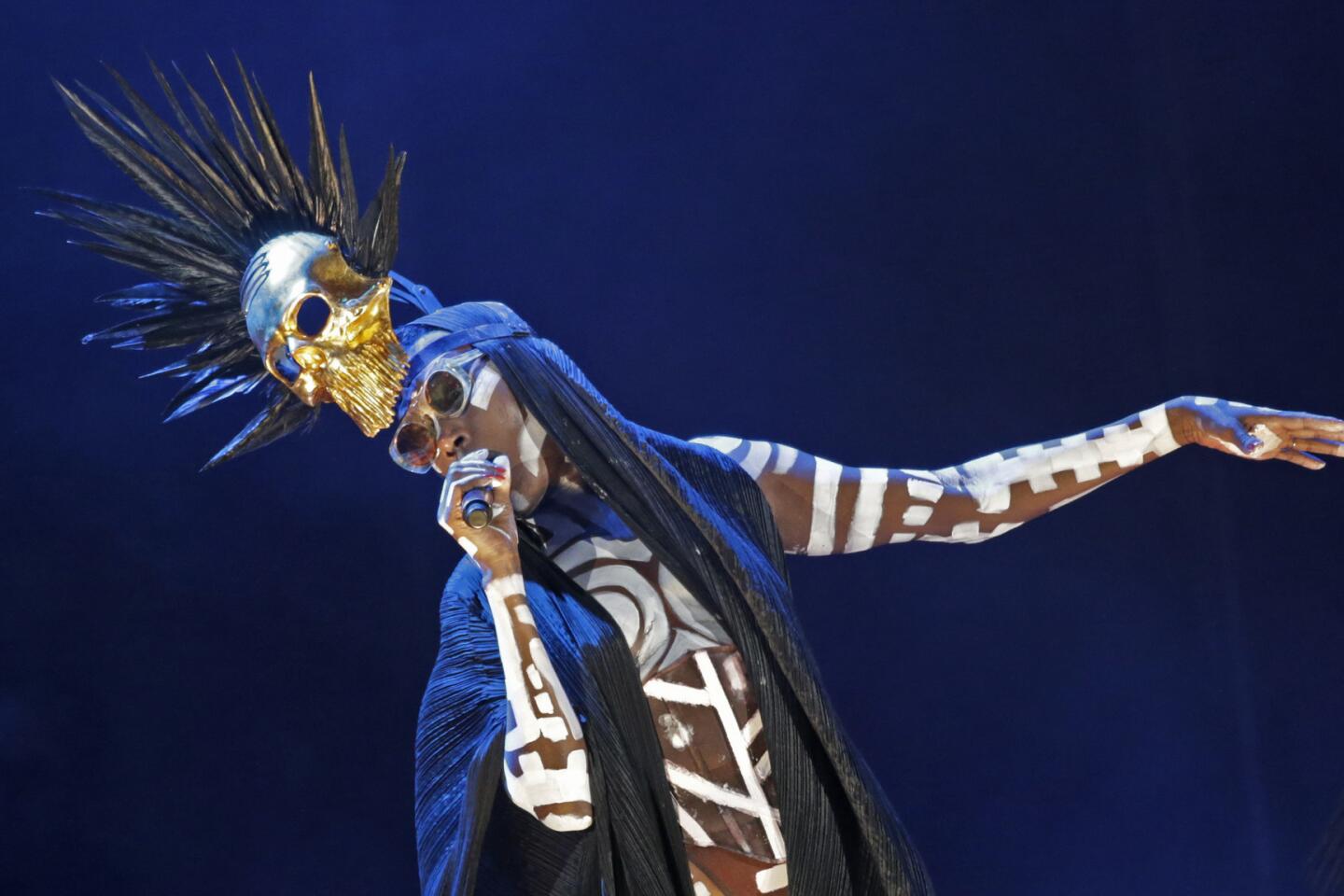

Grace Jones in concert at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles on Sep. 27.

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 7/82

Lauryn Hill performs at the Greek Theatre on Sept. 14, 2015. Read the review.

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 8/82

Little Big Town band member Phillip Sweet performs at the Greek Theatre in Los Angeles on Sept. 10.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 9/82

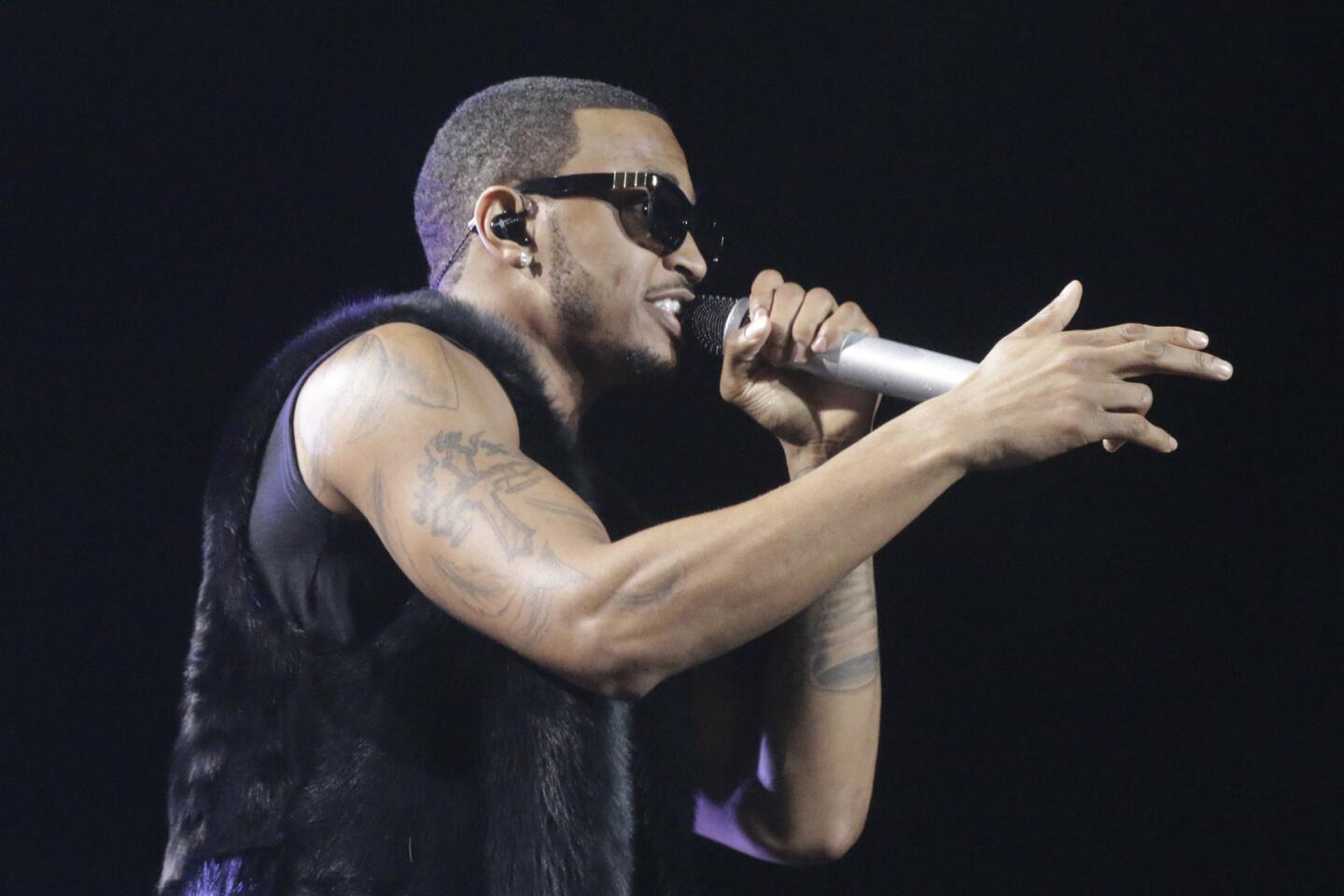

Miguel performs at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery on Sept. 4, 2015. Read the review.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 10/82

D’Angelo and the Vanguard performs at FYF Fest at Exposition Park on Aug. 23, 2015. Read the review.

(Christina House / For The Times) 11/82

Morrissey takes the stage at FYF Fest on Aug. 23, 2015. Read the review.

(Christina House / For The Times) 12/82

Solange onstage at FYF Fest on Aug. 23, 2015.

(Christina House / For The Times) 13/82

FKA Twigs performs at FYF Fest at Exposition Park on Aug. 23, 2015.

(Christina House / For The Times) 14/82

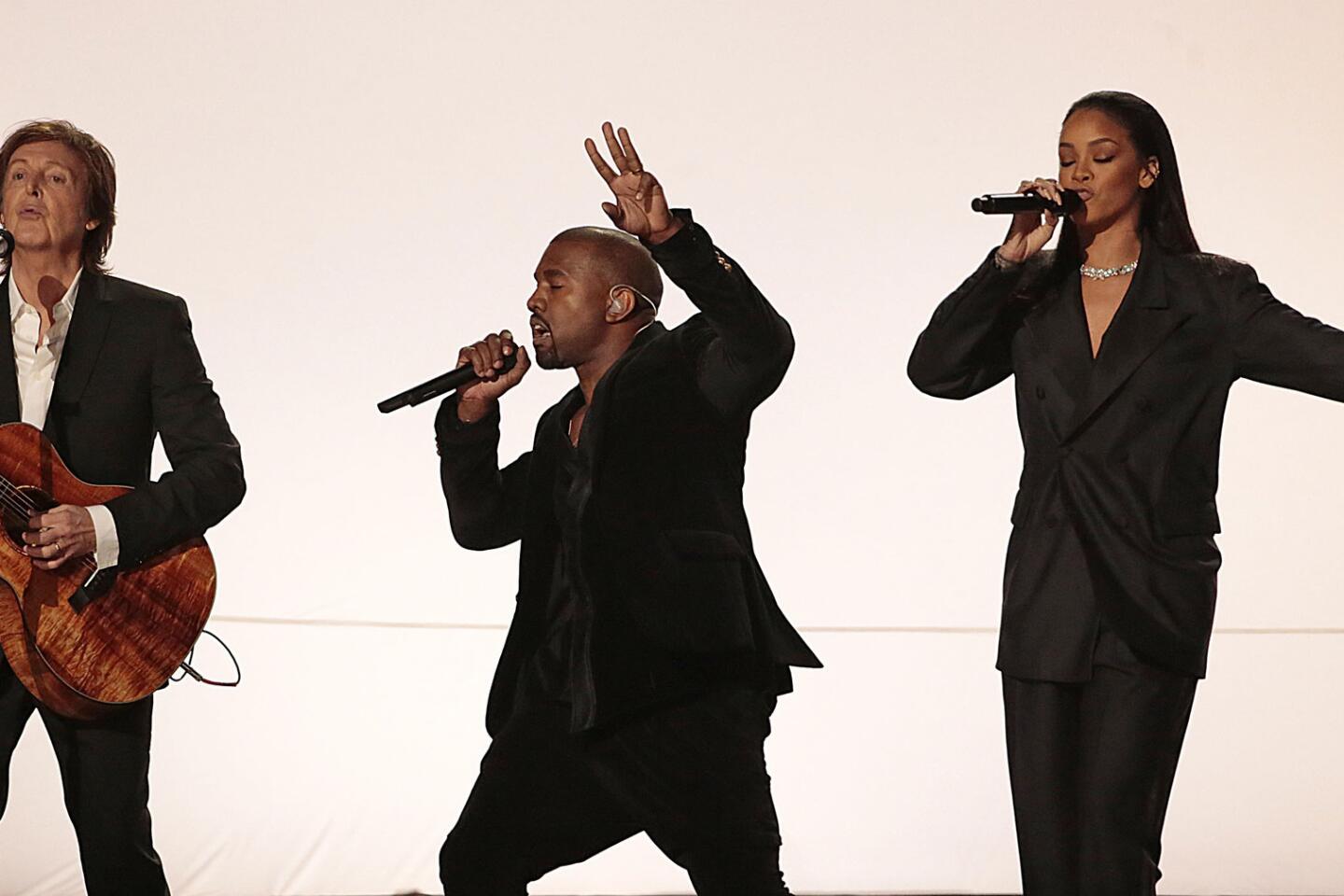

Kanye West performs during FYF Fest on Aug. 22.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times) 15/82

Jehnny Beth performs with Savages at FYF Fest on Aug. 22, 2015.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times) 16/82

Taylor Swift performs at Staples Center in August.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times) 17/82

Shania Twain at Staples Center in Los Angeles on Aug. 20.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times) 18/82

Aretha Franklin at the Microsoft Theatre in Los Angeles on Aug. 2.

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 19/82

The Weeknd performs during Hard Summer at the Fairplex in Pomona on Aug. 1, 2015. Read the review.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 20/82

Mötley Crüe celebrates the end of another concert, at the Matthew Knight Arena in Eugene, Ore., on July 22.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times) 21/82

John Famiglietti, left, front man Jake Duzsik, and Jupiter Keyes of the L.A. experimental band Health performing at the Echo in Los Angeles on July 22, 2015.

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 22/82

Ben Gibbard of Death Cab for Cutie performing at the Hollywood Bowl on July 12.

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 23/82

Kendrick Lamar performing at the BET Experience at Staples Center on June 27.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 24/82

Underworld performs at the Hollywood Bowl on June 21. Read the review.

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 25/82

Brian Wilson at the Greek Theater on Saturday, June 20. It was also his 73rd birthday.

(Michael Robinson Chávez / Los Angeles Times) 26/82

D’Angelo performs at Club Nokia on June 8, 2015. Read the review.

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 29/82

Ciara performs at Club Nokia on May 30, 2015.

(Michael Robinson Chávez / Los Angeles Times) 30/82

U2 guitarist The Edge, left, and lead singer Bono perform at the Forum on Tuesday, May 26. It was the first night of five at the venue.

(Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times) 31/82

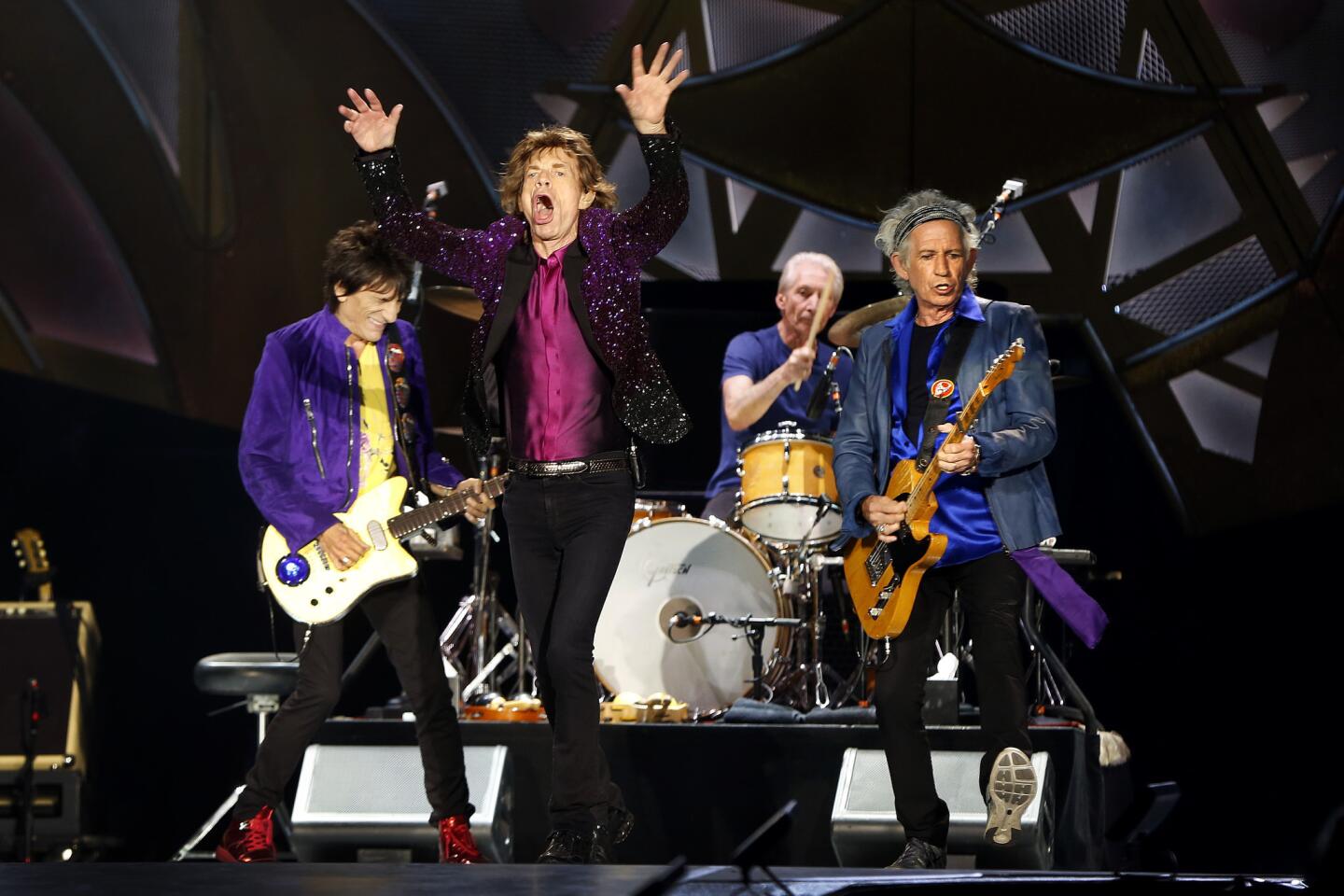

Guitarist Ron Wood, singer Mick Jagger, drummer Charlie Watts and guitarist Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones play Petco Park in San Diego on May 24, on the opening night of their 2015 American tour.

(Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times) 32/82

Neil Diamond performs at the Hollywood Bowl on Saturday, May 23, 2015.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 33/82

Steve Aoki, EDM DJ, producer and recording artist, performs on Broadway between 4th and 6th streets in downtown Los Angeles, May 16, 2015.

(Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times) 34/82

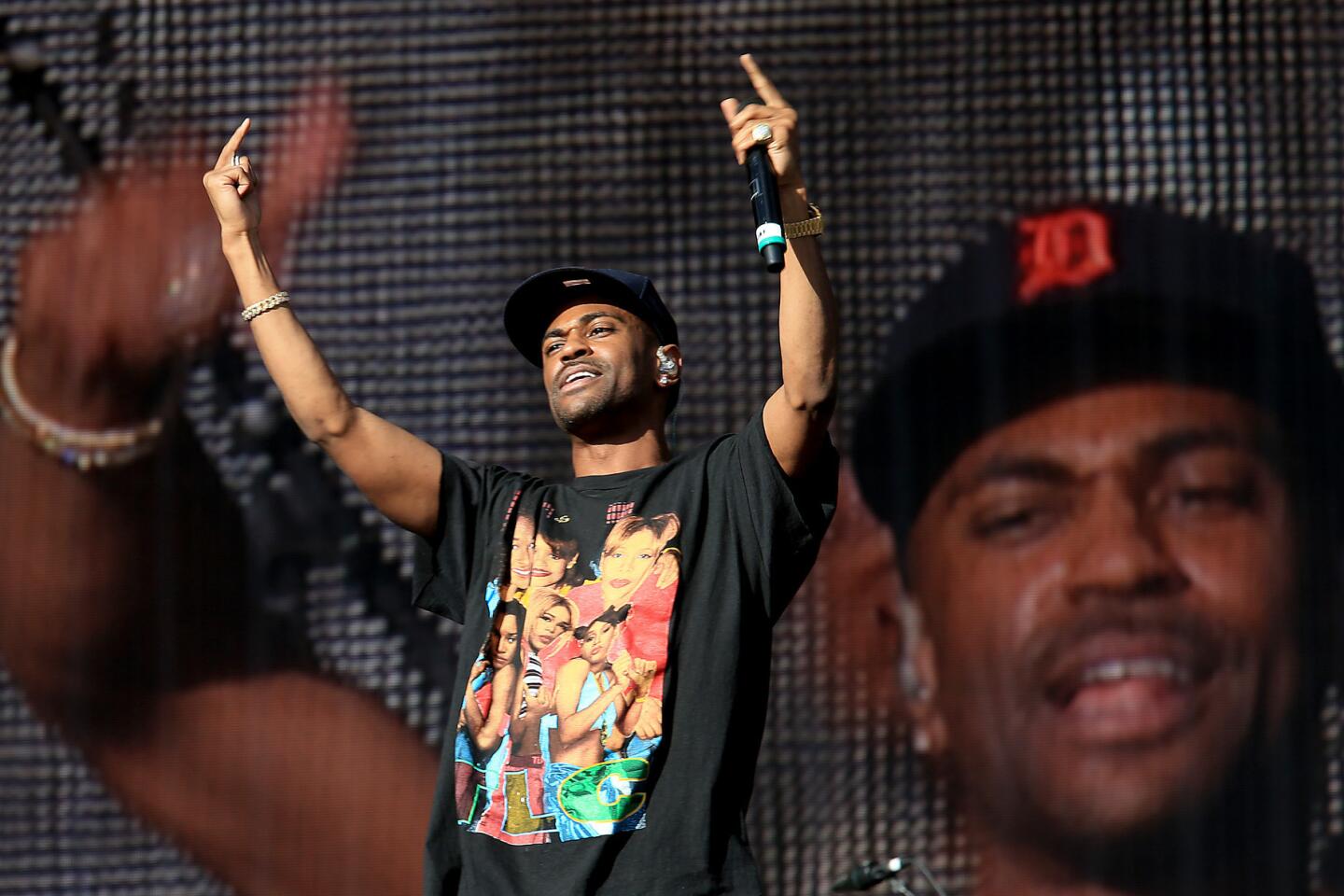

Rapper Big Sean performs at Rock in Rio in Las Vegas on May 16.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 36/82

Sia performs during the Wango Tango concert at the StubHub Center on May 9, 2105, in Carson.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) 37/82

Justin Bieber performs during the Wango Tango concert at the StubHub Center on May 9, 2105, in Carson.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) 38/82

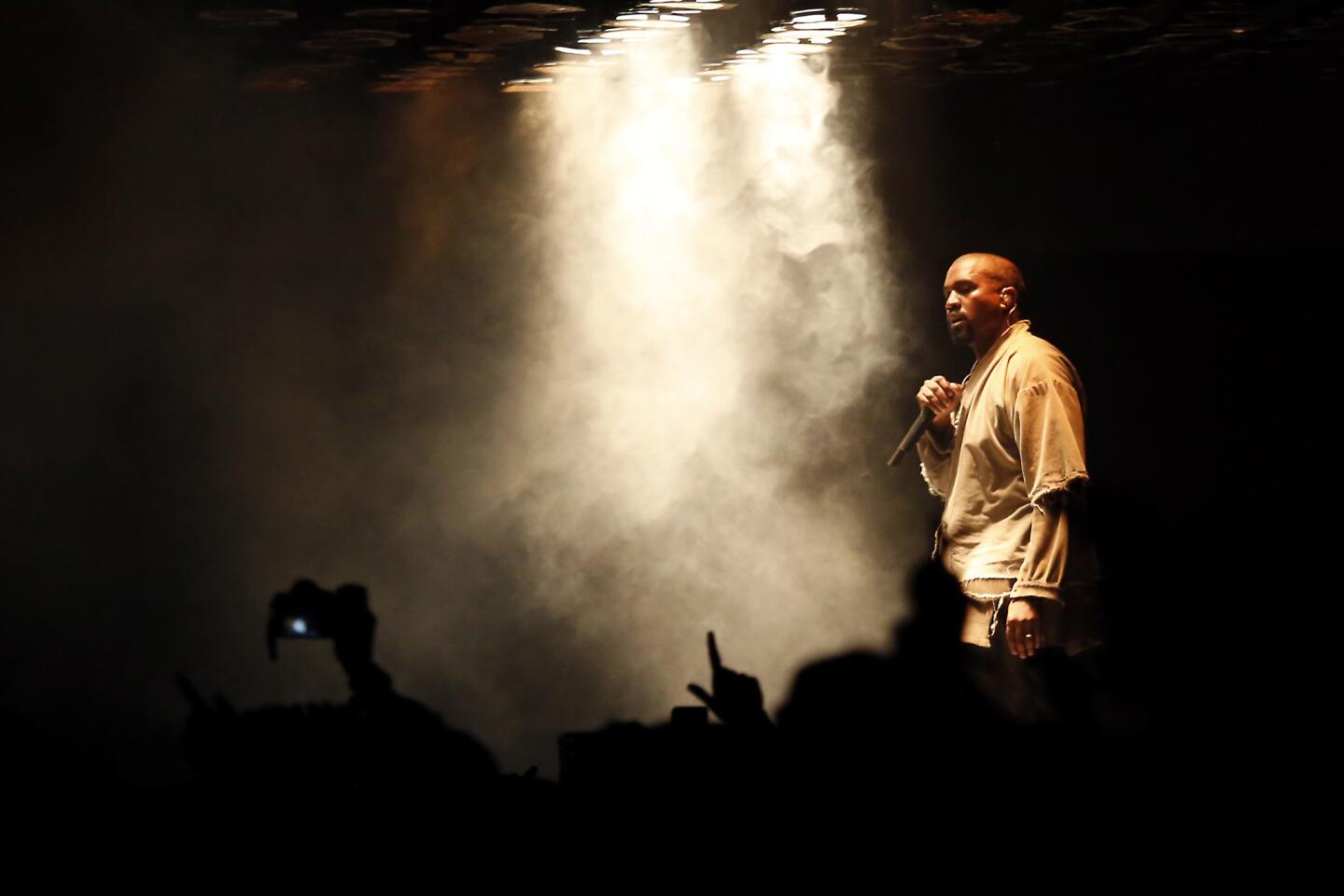

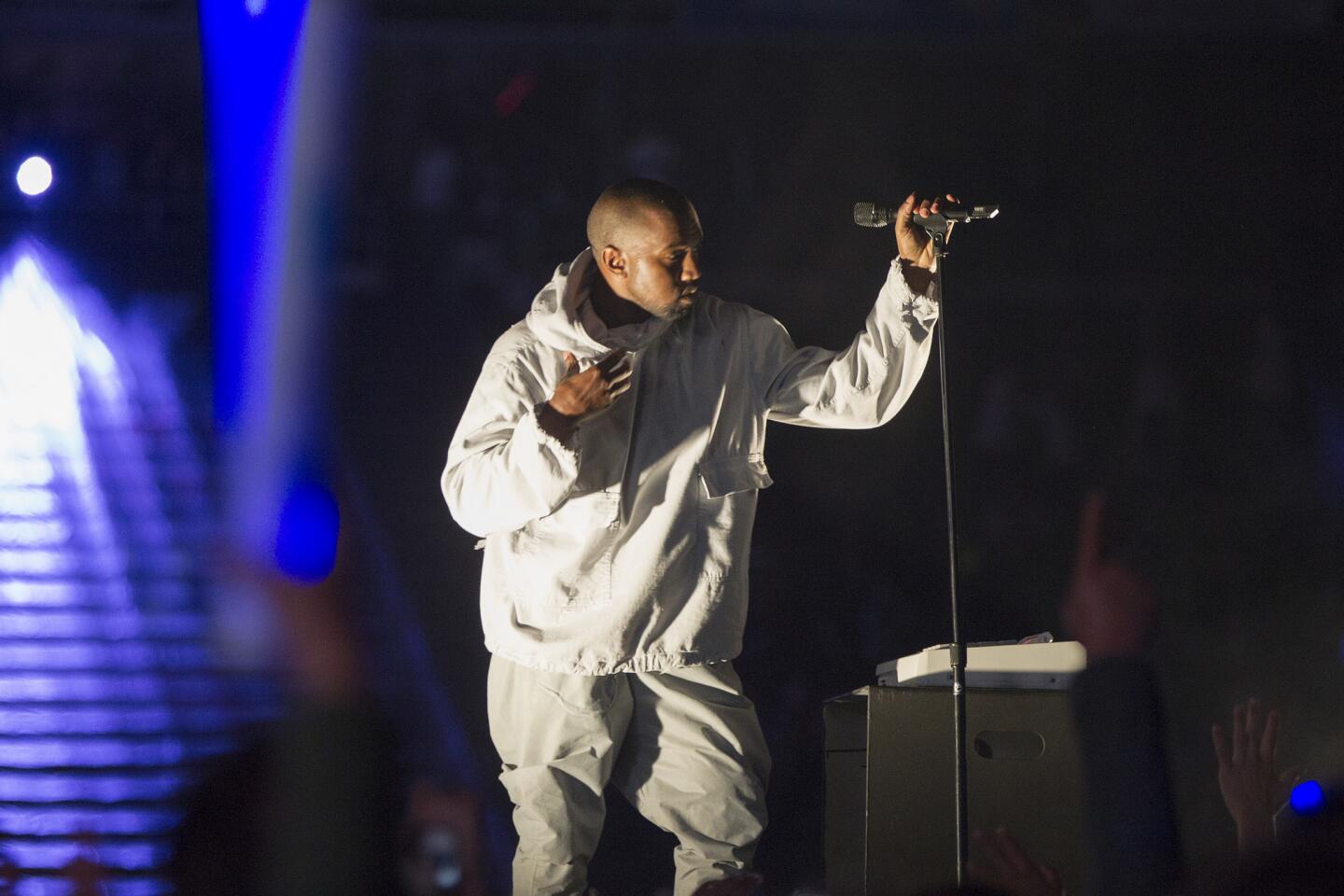

Kanye West performs in shadowy lights during the Wango Tango concert at the StubHub Center on May 9, 2105, in Carson.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) 39/82

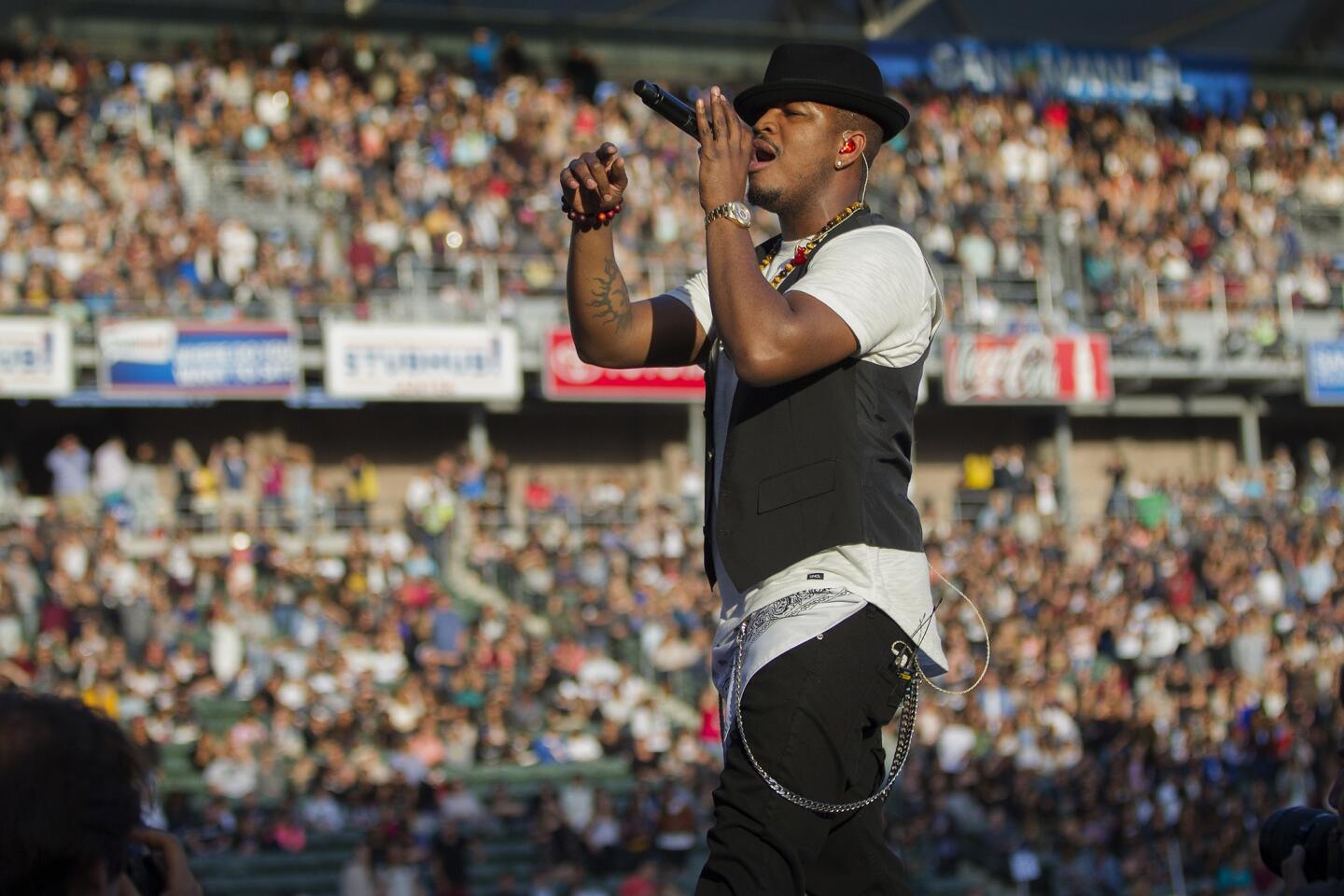

Ne-Yo performs in front of a full house during the Wango Tango concert at the StubHub Center on May 9, 2105, in Carson.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) 40/82

Nick Jonas performs during the Wango Tango concert at the StubHub Center on May 9, 2105 in Carson.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) 41/82

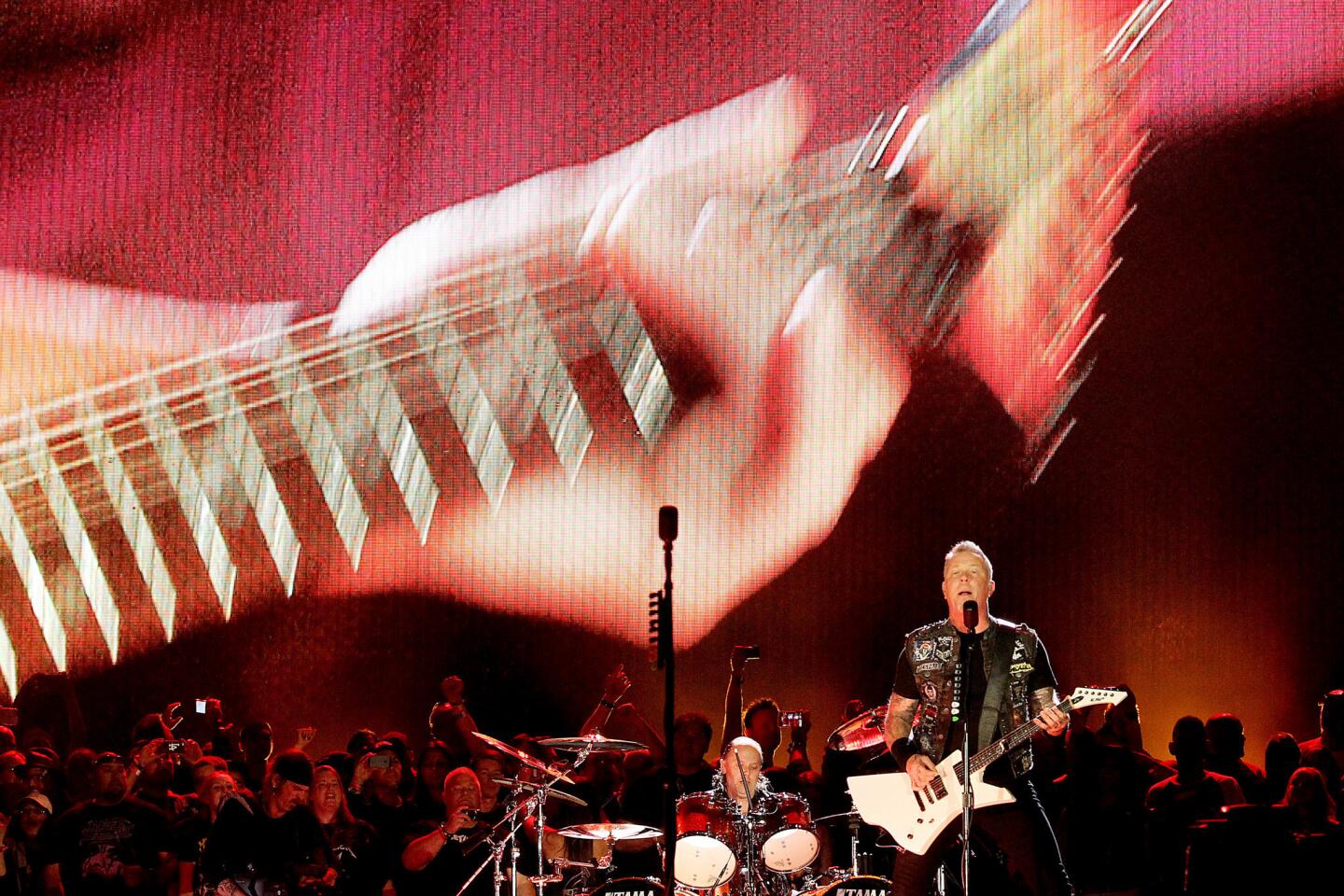

James Hatfield fronts Metallica at the Rock in Rio Festival in Las Vegas on May 9.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 42/82

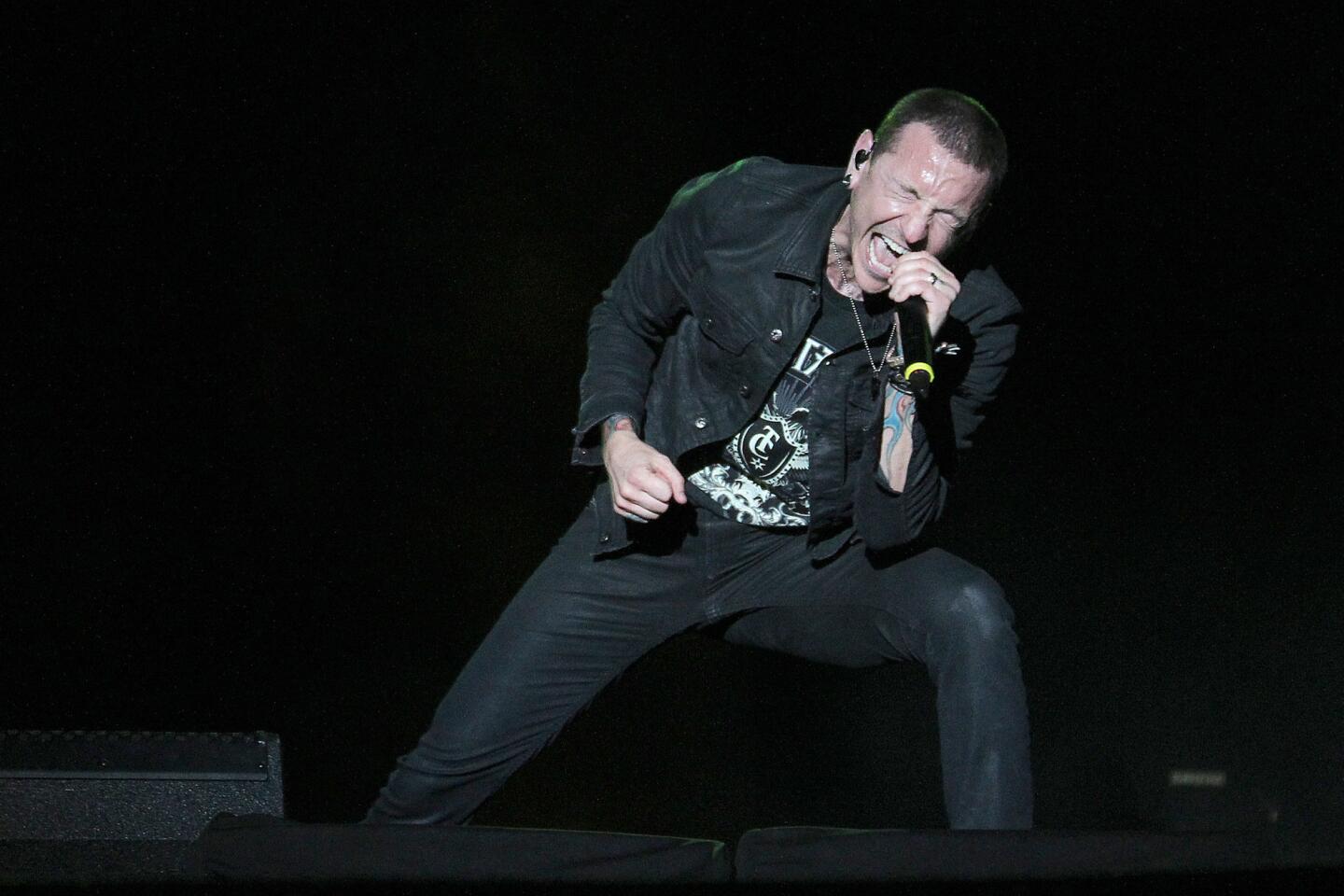

Chester Bennington and Linkin Park play the Rock in Rio fest in Las Vegas on May 9.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 43/82

Tim McIlrath, lead singer for the Chicago-based, melodic hardcore band Rise Against, wades into the crowd at Rock in Rio on May 9.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 44/82

Gwen Stefani fronts No Doubt at Rock in Rio in Las Vegas on May 8.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 45/82

Janet Weiss, left, and Corin Tucker perform during the

Sleater-Kinney concert at the Palladium in Hollywood on April 30.

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 46/82

Carrie Brownstein performs during the

Sleater-Kinney concert at the Palladium in Hollywood on April 30.

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 47/82

Swedish-born soft-indie-rock artist

Jose Gonzalez performs at the Regent on April 30.

(Adam Della / For The Times) 49/82

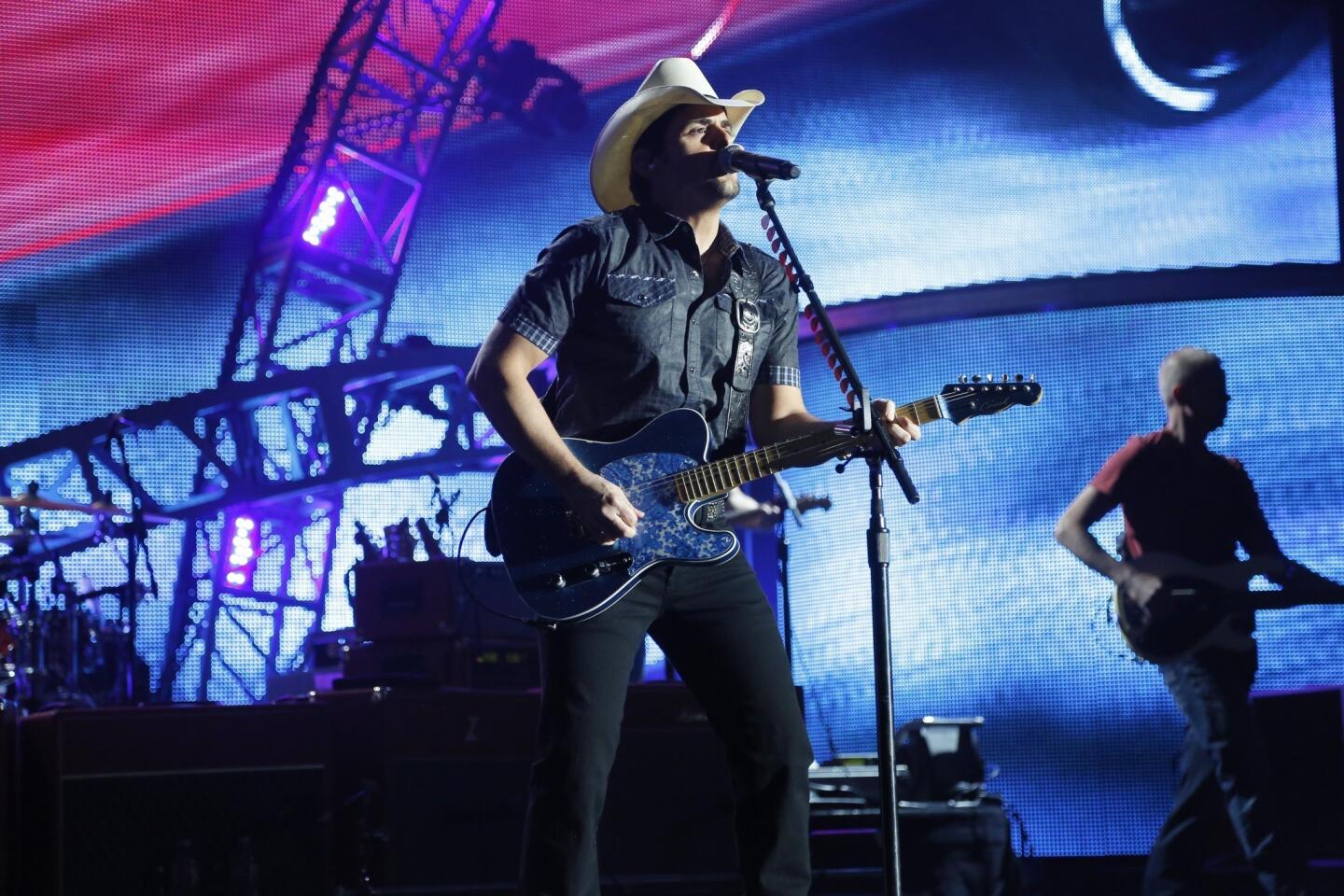

Bassist Dusty Hill, left, and guitarist Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top perform on the Palomino Stage at the

Stagecoach Country Music Festival on April 25.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times) 51/82

Rumer performs at the Masonic Lodge at Hollywood Forever Cemetary in Hollywood on April 23.

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 52/82

Kanye West makes a surprise appearance during the Weeknd’s performance at the

Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival on April 18.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 53/82

Marina and the Diamonds perform at the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival on April 18. (Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times)

54/82

FKA Twigs performs at the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival on April 18. (Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times)

55/82

Barry Manilow performs at the Staples Center on April 14.

(Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times) 56/82

Florence + The Machine perform during the

Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival on April 12.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times) 58/82

El-P, left, and Killer Mike of

Run The Jewels perform at the

Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival on April 11.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 59/82

Brittany Howard of

Alabama Shakes performs at the

Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival on April 10.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times) 60/82

Ariana Grande performs at the Forum in Inglewood, April 8, 2015.

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 61/82

Rivers Cuomo of Weezer performs with his band at Burgerama on March 28. Weezer was one of the headliners for the two-day festival at Santa Ana’s Observatory.

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times) 62/82

Lead singer Zac Carper of FIDLAR performs with his band at Burgerama, the two-day Santa Ana festival thrown by OC DIY impresarios Burger Records.

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times) 63/82

Experimental artist Lustmord makes his Los Angeles debut on March 21 at the Masonic Lodge at Hollywood Forever.

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times) 64/82

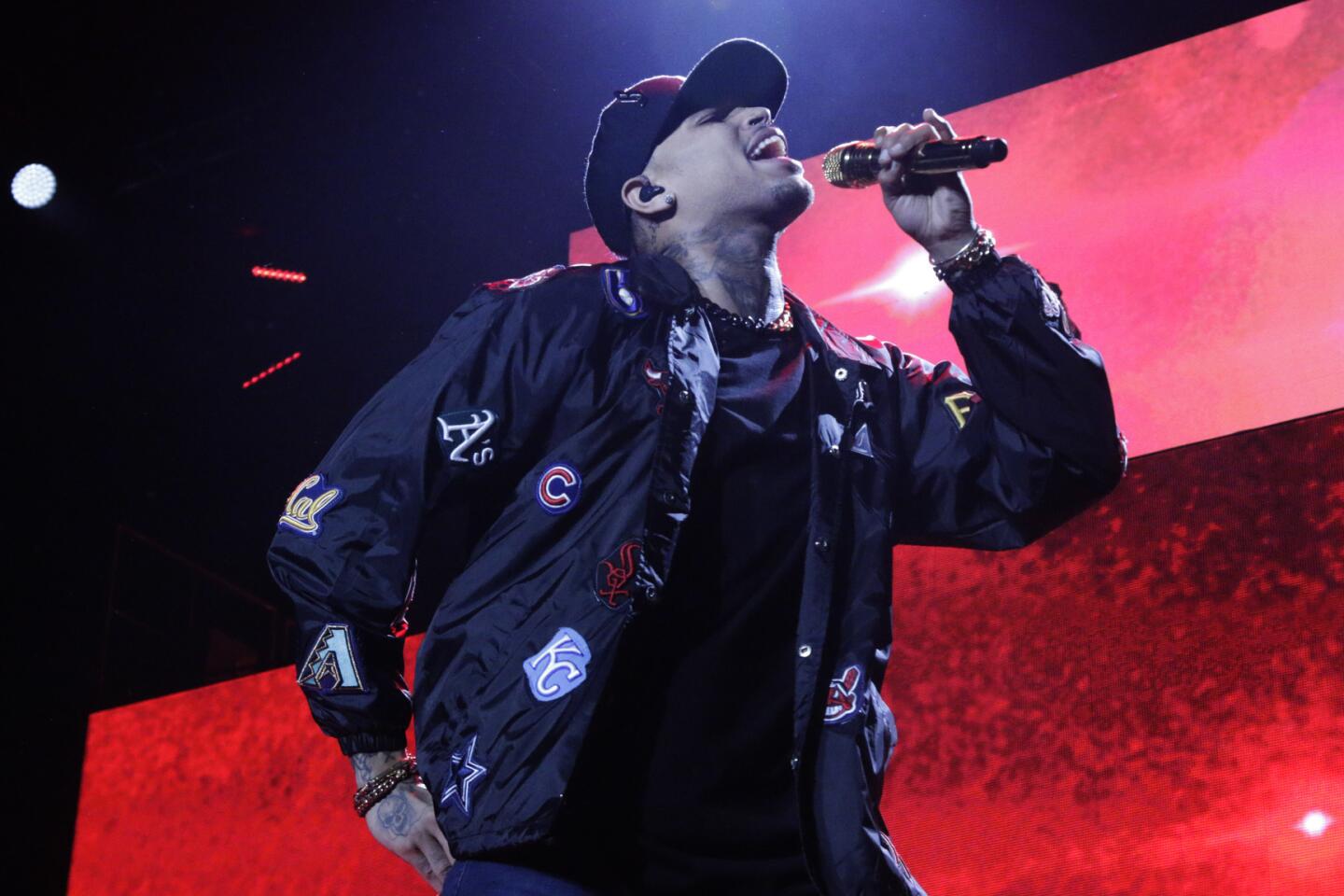

R&B singer Chris Brown performs at the Forum in Inglewood. The March 8 show was a stop on his tour with Trey Songz and Tyga.

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 65/82

Trey Songz performs at the Forum on March 8.

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 66/82

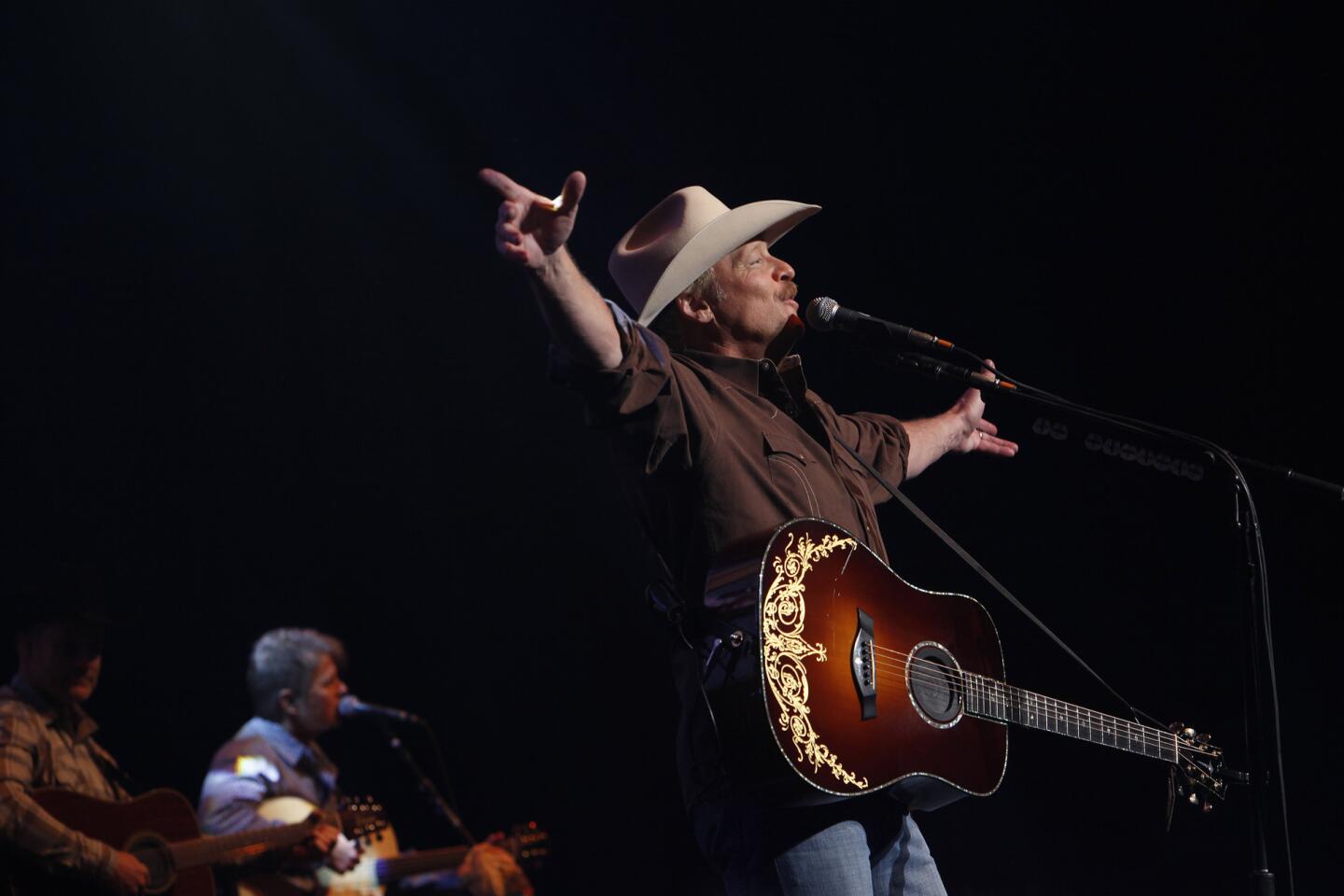

Alan Jackson performs at the Nokia Theatre on Feb. 27 as part of his

Keepin’ It Country tour.

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times) 67/82

Brandy Clark performs as part of Alan Jackson’s

Keepin’ It Country tour at the Nokia Theatre on Feb. 27.

(Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times) 68/82

Caribou performs at the Fonda Theater in Hollywood on Feb. 26.

(Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times) 69/82

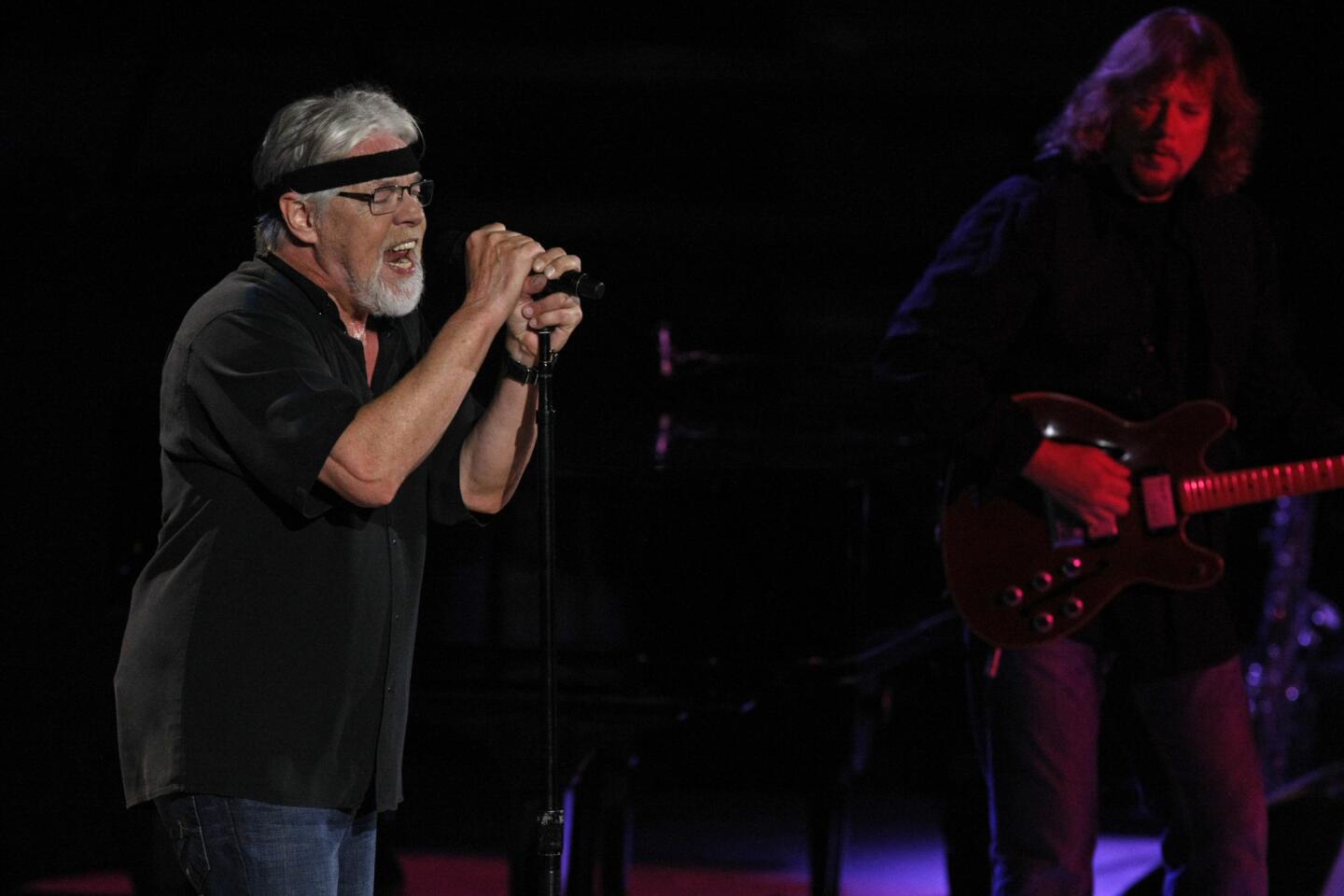

Roots rocker

Bob Seger performs at the Viejas Arena at San Diego State University on Feb. 25.

(Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times) 70/82

Tegan and Sara perform with the Lonely Island during the 87th

Academy Awards on Feb. 22 at the Dolby Theatre in Hollywood.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 71/82

Sarah Barthel of Phantogram performs at the

Air + Style concert and snowboarding event at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena on Feb. 21.

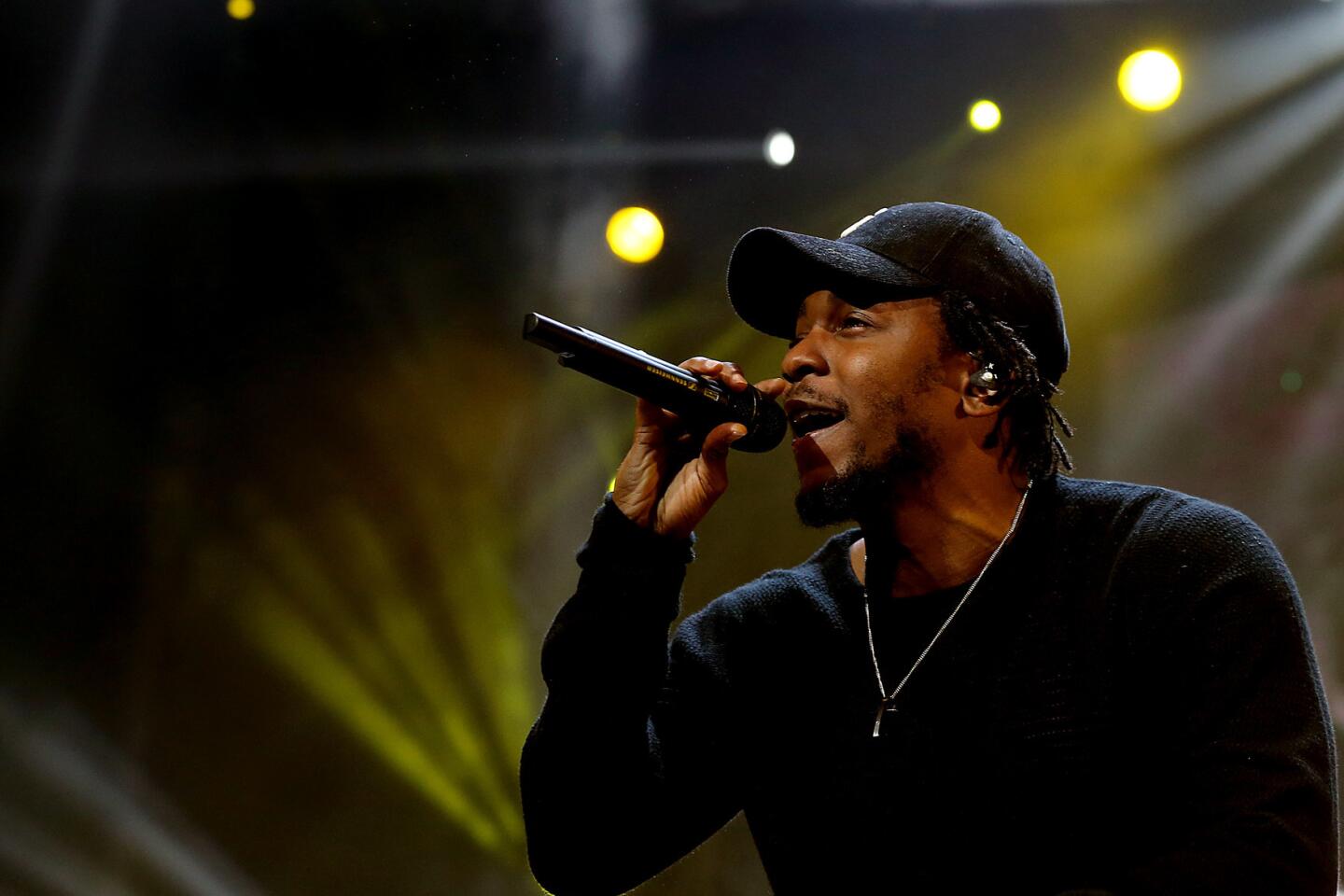

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times) 72/82

Kendrick Lamar performs at the Air + Style concert and snowboarding event at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena on Feb. 21.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times) 73/82

John Legend performs during a rehearsal for “Stevie Wonder: Songs in the Key of Life - An All-Star Tribute” on Feb. 9 at Nokia Theatre in Los Angeles.

Read the review (Christina House / For The Times) 75/82

Madonna interacts with a dancer during the 57th Grammy Awards on Feb. 8.

Read the review (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times) 77/82

Patti Smith at the Roxy on Feb. 2.

Read the review (Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times) 78/82

R&B singer Tinashe sings to a packed crowd at the El Rey Theatre on Jan. 22.

Read the review (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) 79/82

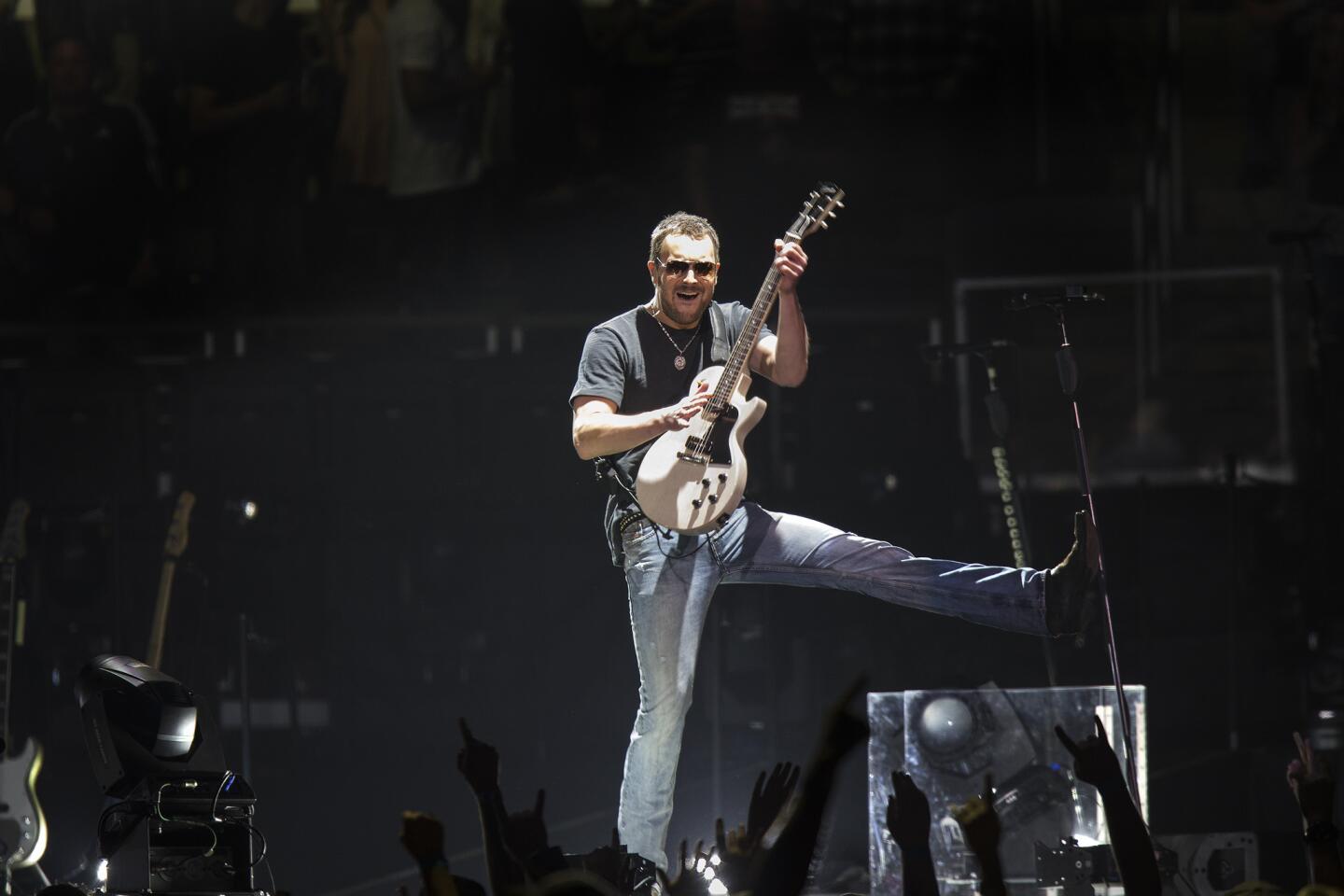

Eric Church rocks the house while performing at Staples Center on Jan. 23.

Read the review (Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times) 80/82

Trombone Shorty & Orleans Avenue performs at the Grand Plaza during the 2015 NAMM show at the Anaheim Convention Center on Jan. 22. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

81/82

Sam France of Foxygen performs at the Roxy on Jan. 2.

Read the review (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times) 82/82

Foxygen at the Roxy on Jan. 2. (Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times)

As for the complex interaction of algorithms and human hands that created “Ae_Live,” Booth offered this explanation. “Only some aspects of the system are consistent. For example, most of the note sequencing is different each time, but the overall ‘flavor’ of each track is consistent. Each track has a range of possibilities, most of which are determined by a set of conditionals. We share data with each other, which we can tell our own stuff to ignore or not, depending on how much we want to deviate. A lot of aspects of the software’s activity can be shared slightly in advance as well, so we can have instantaneous reactions. You do get this sometimes in jazz, obviously, but it’s slightly a guessing game a lot of the time what each person’s going to do. There’s a rough script, but we have a lot of latitude. We tend to deviate very subtly because it’s easy to just throw something into chaos. But sometimes we do that too.”

That’s as good a vernacular explanation as I’ve heard of what is, in this case, both the user manual and the score. You’ve heard the joke about electronic musicians standing on stage with laptops, maybe checking email for all the audience knows? Autechre’s live show is the opposite of that.

Still, Autechre makes none of this easy on themselves or their audience. It is sort of hard to have a hit when you essentially have no melodies, or songs; just rhythmic hashing of waveforms not generated by human hands and later processed by software.

If you tried to use a live instrument to play a track from “Exai,” say, “irlite (get 0),” you might be able to mimic the series of notes that unfold over the last two minutes of the track. If you pulled it off, you might sound like Derek Bailey trying to sit in with Weather Report. As for mimicking the half-dozen other howling sounds circling the notes, good luck.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter >>

In many ways, Autechre is the realization of critical theory formed in France during the ‘60s, which then reached American academia in the ‘80s. Writing in 1963 on the work of Georges Bataille, the artist and author Pierre Klossowski articulated the following idea: “For if the simulacrum tricks on the notional plane, this is because it mimics faithfully that part which is incommunicable. The simulacrum is all that we know of an experience; the notion is only its residue calling forth other residues.”

By 1980, Jean Baudrillard has filtered the idea of the simulacrum and coined a formulation seen often now: “the copy of a copy without an original.”

Autechre’s music is the remix of a song that never existed, the distortion of a signal from nowhere. Though Autechre’s music is almost entirely removed from the physical world — until it is amplified and becomes a physical presence that moves plenty of air — what happens inside their boxes is a gleeful sort of manhandling, digital fistfuls of sound being squeezed. “Ae_Live” is that clay being torqued and flattened by their programs, a body of work that is rarely dry or pointlessly obscure. It is the joy of machines, guided and preserved by two benevolent shepherds.

Follow me on Twitter @sfj