Philippa Gregory balances fact and fiction

The publication of two books this season by Philippa Gregory gives us not only two more fascinating portraits of a fascinating period in English history, it also opens an unexpected window into the way the bestselling author of “The Other Boleyn Girl” plies her craft.

“The Women of the Cousins’ War” (Touchstone: 342 pp., $26) — written with historians David Baldwin and Michael Jones — is a work of nonfiction that presents the lives of three Wars of the Roses figures: Elizabeth Woodville, wife of Edward IV; Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII; and Elizabeth’s mother, Jacquetta, duchess of Bedford (the section on Jacquetta is written by Gregory). Gregory’s other new book, “The Lady of the Rivers” (Touchstone: 453 pp., $27.99), is a novel about Jacquetta’s early life.

Taken together, the books give readers some idea how a novelist can take the merest thread of historical detail and invent a scene that feels faithful to that historical figure’s circumstances. I caught up with Gregory in between segments of her author’s tour in the following email exchange:

“The Lady of the Rivers” and “The Women of the Cousins’ War” seem to comment on each other in a fascinating way. Was it your intention that the two books would show readers how writing history and writing historical fiction are different?

I didn’t have anything like a grand idea of demonstrating how the two are different, though as I was writing them alongside each other, I found I was thinking about the differences all the time as I was experiencing them. Of course, now you say it, I see that the reader will have a parallel experience to mine as they move from the factual to the fictional and perhaps back again.

My intention was to provide the readers of the fictions with three factual essays to serve as “companions” to the novels. So many people ask me where the history ends and the fiction begins that I now provide a bibliography of history books at the end of every novel so people can discover for themselves. In the case of Jacquetta, there is nothing in general publication at all. My research on Jacquetta produced files and files of notes, so I thought that I might as well write an essay on her for readers to study, if they so wished.

Did you learn anything in the process of writing about the same life twice?

What became really clear to me was how much the history (just like a novel) is a process of selection of facts based on the interest and prejudices of the historian. We all know that history is subjective, but it was a very powerful experience for me to see how the material that struck me as important for understanding the historical character was exactly the material that struck me as interesting as a novelist. What is revealed in both the novel and the history is the life of Jacquetta and, of course, the interests of the author.

The other thing that really struck me — and this is rather technical — is the difference in language. Often the scenes in the history and the fiction are almost identical but the descriptions are totally different. The fictional scene uses far more active and interesting verbs, and is designed to evoke emotion in the reader. It is also written with an eye to lyricism of language, and even how the paragraphs look on the page. Ideally, the novel is a thing of beauty. The history is more restrained and dry. I suspect that as readers we confuse coolness with accuracy and that we all think that detachment is “scientific.”

Gaps in historical records seem less problematic for a novelist. In “Lady,” an absence of specific information allows you to take your 15th century heroine Jacquetta — whose daughter Elizabeth Woodville is caught at the center of the War of the Roses — and reasonably place her in the company of Joan of Arc. It must have been thrilling to discover that their two lives overlapped.

I had a bit of a hurrah moment when I discovered that the man who arrested Joan of Arc and released her to her death at the hands of the English was Jacquetta’s uncle. At the time of Joan’s arrest, we don’t know where Jacquetta was living, but she may well have been staying at her uncle’s chateau. We know that her brother lived there during his boyhood and married his uncle’s ward. We have sound historical accounts of the women of Jacquetta’s family befriending Joan and trying to persuade her to avoid charges of heresy by changing into women’s clothes. Jacquetta’s aunt and great-aunt were named by Joan at her trial as women who had befriended her. So there is a terrific connection there.

Jacquetta’s world is far less familiar to us than the Tudor era. I had no idea, for instance, that the alchemical quest was used by some not for occult reasons but to create gold to pay armies. Were there any special research challenges that you had to overcome to make such discoveries?

As you see, I had to study some histories of alchemy and also study French history that was unfamiliar territory to me. The reading I did into alchemy was tremendously illuminating, and, thanks to Jacquetta, I also studied herbalism, lunar planting and Tarot cards. It’s funny to think that there are more registered practicing alchemists today than there were in the 15th century. It’s not so strange and occult; at one end of the spectrum it is chemistry and at the other traditions of meditation and purification.

How did David Baldwin (writing about Woodville) and Michael Jones (writing about Margaret Beaufort) become involved in “The Women of the Cousins’ War”?

I had met both historians when I was working on fictional accounts of the women that they had described in their biographies. In both cases they were kind enough to each read the manuscript of the relevant novels and give me some advice. When I realized that there was nothing much on Jacquetta, and that if I wanted my readers to have an essay on her I would have to write it myself, I went to these two historians and asked them if they would like to contribute an essay on “their” character for us to publish all three together. Interestingly, the history of women is still so little regarded that at the time both their very fine biographies were out of print. They were pleased to write with me, and we did some author talks together, and are considering another book.

You’re trained as a historian with a doctorate from the University of Edinburgh. Your career could have been so very different if you had taken the historical scholar’s road. What made you decide to tell history as a novelist?

This is one of those serendipitous turns in the road. I wanted to be an academic but when I finished my PhD in 1984 there had been terrible cuts to 18th century courses in the English universities and I could not get a job. As I applied for posts, I wrote my first novel, almost as entertainment for myself. As I became more and more interested in it, I thought it was publishable. I sent it to an agent, she sent it out to publishers, they held an auction and it became a worldwide bestseller: “Wideacre.” It’s an extraordinary story of luck, timing and the right book.

The spirit of Joan of Arc hovers over Jacquetta’s entire life. Not just the accusations of witchcraft that both faced, but also Joan’s belief in the Wheel of Fortune. How did you come to realize that Jacquetta’s own life was fittingly symbolized by the wheel?

In Jacquetta’s lifetime all playing cards carried the symbols that we now think of as belonging to the Tarot pack, so I knew she would have been familiar with the symbols. She stood trial as a witch and evidence was produced of her “charming” the marriage of her daughter and son-in-law. I think it very likely that she tried to influence events by what she would have thought was magic. Certainly she had a family tradition of a water goddess as the founding matriarch of the House of Luxembourg — a myth so rich and wonderful that I could not have made it up. I wanted her to learn to read the cards as a fortune-telling device and also to use charms. I studied the Tarot and thought that the Wheel of Fortune was a magnificent symbol for Jacquetta’s life but even more for the life of Margaret of Anjou, who was Queen of England and France and died penniless in exile.

I see new books about the Tudors on the publishing horizon. Why do audiences never tire of the Tudors and related periods?

I don’t know, and I feel I should know, but I can only judge by myself. I think there is something pleasurable about the retelling of material that one knows. We all know that Henry VIII had six wives and most of us have an idea about the women and the marriages, and to read (or watch) the story retold is a pleasure like having a bedtime story read and reread. It’s familiar and yet each time it’s fresh. Why the Tudor period is because I think there are elements in this particular time in history which speak to so many people: those who are fascinated by Elizabeth or in love with Mary Queen of Scots, those who have an interest in Katherine of Aragon or the complex interesting woman who was Anne Boleyn, not to mention her less known sister. Then there is the period itself, a time when England was becoming England and making the myths that we now recognize: Protestant, insular, capitalist, imperialist. For historians, it’s a wonderful period of change and development; for the general reader, it’s very rich; and for the novelist, there is so much recorded of interest and so much to discover. I am working on the Plantagenet family who preceded the Tudors for the next few novels, but I feel certain that I will return to the Tudors at some time. They go on fascinating me as well as everyone else.

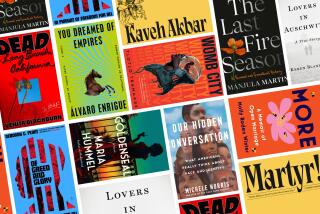

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.