Bay Area cities have banned gas to fight climate change. But not Los Angeles

This is the Feb. 4, 2021, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Over the last two years, 42 California cities and counties have banned or discouraged gas hookups in new buildings. The policies vary from place to place, but the goal is to shift homes and businesses from gas furnaces and stoves — which generate planet-warming emissions — to electric alternatives such as heat pumps and induction cooktops.

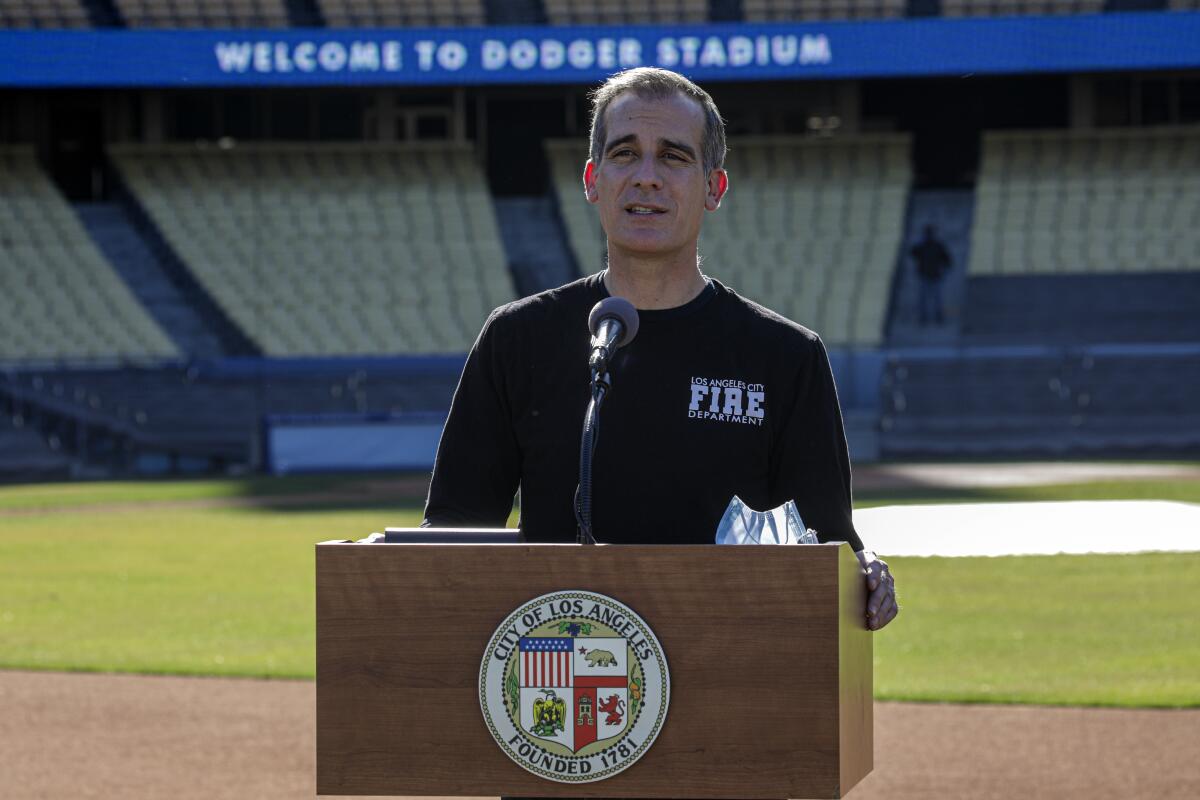

Los Angeles had hoped to be a leader in this area. The sustainability plan released by Mayor Eric Garcetti in April 2019 said all new buildings should be “net-zero carbon” by 2030, with existing buildings converted to zero-emission technologies by 2050.

Since then, Oakland, San Francisco and San Jose have banned natural gas in all or most new buildings. L.A. has not. What gives?

To answer that question, I asked all 15 members of Los Angeles City Council what they think about the idea of banning or discouraging gas hookups in new construction, or requiring new buildings to be all-electric. I got responses from 10 of them.

But before we get to that, some quick context.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

First, gas burned in homes and businesses accounts for about 10% of California’s climate pollution. That’s not nearly as big a slice of the pie as transportation, the state’s biggest emitter. But as the climate crisis wreaks ever-greater calamity — through record heat, more destructive fires and fast-rising seas — action is needed to slash emissions across every part of the economy.

It’s also important to recognize that a ban on gas hookups wouldn’t reduce emissions from existing buildings, and that climate isn’t the only consideration. Officials in Garcetti’s office say they’re working to craft policies that will not only slash carbon emissions from new and existing buildings, but also do so in a way that sustains job opportunities for gas utility workers, and benefits low-income families and communities of color by reducing indoor air pollution from gas stoves without raising energy bills.

“We really want to prioritize the multifamily affordable housing sector,” Lauren Faber O’Connor, the city’s chief sustainability officer, told me. “Our policies and our incentives and our financing programs, as we design them, will be very keenly aware of the need to design toward equity and engage those front-line communities directly.”

Last week, Garcetti hired Marta Segura to be the first director of the city’s newly formed Climate Emergency Mobilization Office. Environmental justice activists see the equity-focused office as an opportunity for them to help shape policy.

“If we electrify everything, how are we going to ensure for low-income communities that they aren’t paying more in energy costs?” asked Martha Dina Argüello, executive director of Physicians for Social Responsibility-Los Angeles.

If city officials hope to phase out natural gas, they will also need to deal with pushback from Southern California Gas Co., which has fought all-electric building codes in San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara and in the summer sued state officials over climate policy.

Company spokesman Chris Gilbride told me via email that achieving California’s climate goals “depends in large measure on SoCalGas’ success in its mission to build the cleanest, safest and most innovative energy company in America,” a reference to the utility’s plans — disputed by environmental activists — to replace some of the fossil fuel in its pipelines with renewable gases.

Eric Hofmann — president of Utility Workers Union of America Local 132, which represents SoCalGas employees — said gas workers support reducing emissions from buildings through efficiency and cleaner fuels, but not electrification. All-electric building codes, he said in an email, are a more costly solution that pose “significant barriers to addressing the housing crisis.”

This battle is playing out nationally too. Just last week, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio set a goal of banning gas in new construction by 2030, and Seattle banned gas heating in new commercial and some apartment buildings. Gas companies are fighting back; four state legislatures have passed laws prohibiting cities from banning gas, and similar bills have been proposed in 10 other states.

Alright, you’ve waited long enough. Here’s what I heard from Los Angeles City Council members about their views on banning or discouraging gas hookups in new buildings:

DISTRICT 1, GIL CEDILLO: No response.

DISTRICT 2, PAUL KREKORIAN: Supportive.

- Krekorian said some kind of all-electric building policy “definitely appeals to me.” But in a city “as big and complex” as L.A., the costs and benefits require careful study, he told me. He wants to avoid getting in the way of housing production, for instance. He’s also awaiting a Department of Water and Power study exploring how the city can get to 100% clean electricity, the results of which will help determine how much climate pollution can be avoided by switching buildings from gas to electricity.

DISTRICT 3, BOB BLUMENFIELD: Supportive.

- “I believe that’s the way we should be headed, especially as more green power options become cheaper and cheaper. While there are nuances to this issue as we don’t want to inadvertently hinder the construction of housing that we desperately need, they are not insurmountable. The obvious environmental benefits cannot be ignored and I think this is something the City Council should take seriously,” Blumenfield said in an email.

DISTRICT 4, NITHYA RAMAN: Supportive.

- “Los Angeles aspires to be a global leader in combating climate change and becoming carbon neutral. Forty-two cities — including Berkeley, San Jose, Oakland and San Francisco — have all adopted building codes to reduce their reliance on natural gas, while L.A. has yet done nothing. It is high time that L.A. develop and pass a policy banning gas hookups in new construction,” Raman said in an email.

DISTRICT 5, PAUL KORETZ: Neither supportive nor opposed.

- Koretz “wants to ensure the City thinks carefully about the impacts of climate, toxic pollution and any legislative action on Indigenous, front-line and labor communities,” spokesman Andy Shrader said in an email. “He wants to develop a holistic approach via the (Climate Emergency Mobilization Office) through a Community Assemblies process that centers climate resilience, equity, housing and jobs, something you can’t do by moving too fast, banning one thing and figuring it out later.”

DISTRICT 6, COUNCIL PRESIDENT NURY MARTINEZ: No response.

DISTRICT 7, MONICA RODRIGUEZ: No response.

DISTRICT 8, MARQUEECE HARRIS-DAWSON: Neither supportive nor opposed.

- “Council member Harris-Dawson doesn’t feel like this story impacts South L.A. unless it has an environmental equity or justice angle. He’s focused on new buildings being as energy efficient as possible and address long-standing health concerns that have plagued the area for generations,” spokesman Antwone Roberts said in an email.

DISTRICT 9, CURREN PRICE: No response.

DISTRICT 10, MARK RIDLEY-THOMAS: Neither supportive nor opposed.

- “We must acknowledge that buildings are a critical culprit in driving up our carbon footprint. L.A. City is uniquely suited to continue to drive innovation and make a significant difference in the health of our communities with a mix of requirements and incentives that move us to a greener and more sustainable built environment. We must be open to exploring new ideas,” Ridley-Thomas said in an email.

DISTRICT 11, MIKE BONIN: Supportive.

- Bonin said he’d been discussing an all-electric building policy with other council members before the pandemic and is “eager to bring it back.” While banning gas in new buildings “can be a controversial issue, it’s sort of the low-hanging fruit and the most sensible and easy step to take,” he told me. He’d like to offer financial incentives for people to replace gas appliances, with a focus on disadvantaged communities. He’s hopeful the Biden administration or the state will provide funding.

DISTRICT 12, JOHN LEE: Neither supportive nor opposed.

- “We all have a responsibility to address climate change and I am open to all legislation that helps to reduce our city’s overall carbon footprint. However, we need to do so in a way that doesn’t negatively impact economic development or disproportionately burden low-income families,” Lee said in an email.

DISTRICT 13, MITCH O’FARRELL: Neither supportive nor opposed.

- “We need to continue the transition into 100% renewable and clean energy as soon as possible. We are currently evaluating all the complexities involved, including the considerable costs to go all-electric, and how that could negatively burden low-income households. You can expect accelerated action on this issue in the near future,” O’Farrell said in an email.

DISTRICT 14, KEVIN DE LEÓN: Neither supportive nor opposed.

- “I strongly support reducing our energy load through efficiency and decarbonizing future construction. I am currently working to ensure we engage a broad cross-section of energy experts, labor and environmental advocates to develop, jointly with the mayor and my colleagues, a set of policies to move L.A. forward on this critical issue,” de León said in an email.

DISTRICT 15, JOE BUSCAINO: No response.

One trend you might have noticed? While only four of the 15 were publicly supportive, nobody said outright they’d oppose a gas ban.

And now, here’s what’s happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

As if wildfire smoke weren’t harmful enough, new research suggests it may carry large amounts of fungi and bacteria. That’s according to The Times’ Joseph Serna, who reports that scientists are worried the living microbes could make cancer patients or kids with asthma more vulnerable to infections. Not great. In other news — and if you’re reading this newsletter, you probably don’t need to hear this — California’s deadliest fire was not, in fact, started by a giant space laser, the insane conspiracy theory floated by a Republican congresswoman, as Hailey Branson-Potts, Joseph Serna and Alejandra Reyes-Velarde report.

In a statistic that I still cannot believe is real, heat killed at least 494 people in Arizona last year. That shatters the state’s previous record, which was set in 2019, by more than 200 deaths, as Ian James reports for the Arizona Republic. Last summer was Phoenix’s hottest in recorded history, with a record 145 days above 100 degrees and a record 53 days above 110 degrees.

After decades of study, scientists have identified toxic chemicals such as DDT and PCBs — and also herpes — as likely causes of a mysterious cancer that’s been killing sea lions in California waters. Here’s the story from The Times’ Rosanna Xia, who writes that because marine mammals are much like humans (they nurse their young and live relatively long lives), their long-term health “is a window into the lasting effects of chronic exposure to the many chemicals humans have introduced to the sea.”

POLITICAL CLIMATE

Environmental justice advocates, many of them based in California, have played a key role in shaping President Biden’s appointments and early climate actions. My colleagues Evan Halper and Anna M. Phillips wrote about how Black, Latino and Indigenous activists have built up so much influence in the climate movement, and what that might mean for future policy.

What kind of Environmental Protection Agency chief will Michael Regan be? In a piece that includes the phrase “megawatt smile,” the New York Times’ Lisa Friedman profiled the North Carolina regulator, writing that he’s known as a consensus builder. At the Department of Agriculture, meanwhile, Biden nominee Tom Vilsack is promising to make climate change a major focus, which probably means farming practices that suck more carbon from the atmosphere, the Washington Post’s Laura Reiley reports.

Dozens of climate bills have been introduced in the California Legislature this session. Capital Public Radio’s Ezra David Romero has a great rundown on legislation running the gamut from corporate accountability to a 24/7 clean energy standard.

AROUND THE WEST

The long legacy of Los Angeles stealing water from Owens Valley and Mono County is alive and well. In the latest installment of this more-than-a-century-long saga, The Times’ Louis Sahagún reports that L.A. is trying to cut off irrigation water that it’s provided free of charge for decades to ranchers near Mammoth Lakes. City officials have cited climate change and reduced snowpack in explaining why they can no longer spare the water. So far, a court order has prevented the change from taking effect.

Not that you should ever read another newsletter before Boiling Point, but I’ve been thoroughly enjoying Land Desk, a new newsletter from veteran western environment scribe Jonathan Thompson. In one recent edition, Thompson wrote about why establishing a national monument is far from sufficient to protect a sacred landscape, with a focus on Bears Ears in Utah. This week, Thompson explores the consequences, positive and negative, of what he calls “industrial-scale tourism” at national parks.

California’s biggest storms are getting even bigger as the planet warms. The state has been inundated by heavy rains and floods over the last week, with some areas experiencing dangerous mudslides in wildfire burn scars and Highway 1 washing out along the coast near Big Sur. As Bob Berwyn reports for Inside Climate News, climate change is worsening the whiplash between fire and flood, pushing both extremes to become, well, more extreme. And so-called atmospheric rivers are already no picnic; as my colleague Paul Duginski explains, a strong one can transport water at a rate equivalent to 25 Mississippi Rivers.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

General Motors plans to stop selling passenger cars that run on gasoline by 2035. The automaker says its future is almost exclusively in electric vehicles — a dramatic shift for a company that just three months ago was siding with President Trump in a fight with California over clean air standards. Now the hard work begins — and not just for GM. Electric utilities need to do a bunch of work on the power grid to make sure they can keep up with demand from EVs, as the New York Times’ Brad Plumer explains.

What happens to solar panels, wind turbines and lithium-ion batteries when we’re done with them? We need to shift to cleaner power sources to tackle the existential threat of climate change. But we should also be thinking about how best to recycle and dispose of renewable energy technologies that contain hazardous materials, as Amy Joi O’Donoghue reports for Deseret News.

Even if the federal government never issues another oil or gas lease, existing leases and permits threaten underground caves in New Mexico. There’s no threat of drilling within Carlsbad Caverns National Park, but the region is home to a sprawling and interconnected underground landscape of limestone and gypsum, much of which has never been mapped, as Jennifer Oldham reports in a fascinating story for National Geographic. Fossil fuel extraction also threatens drinking water aquifers.

ONE MORE THING

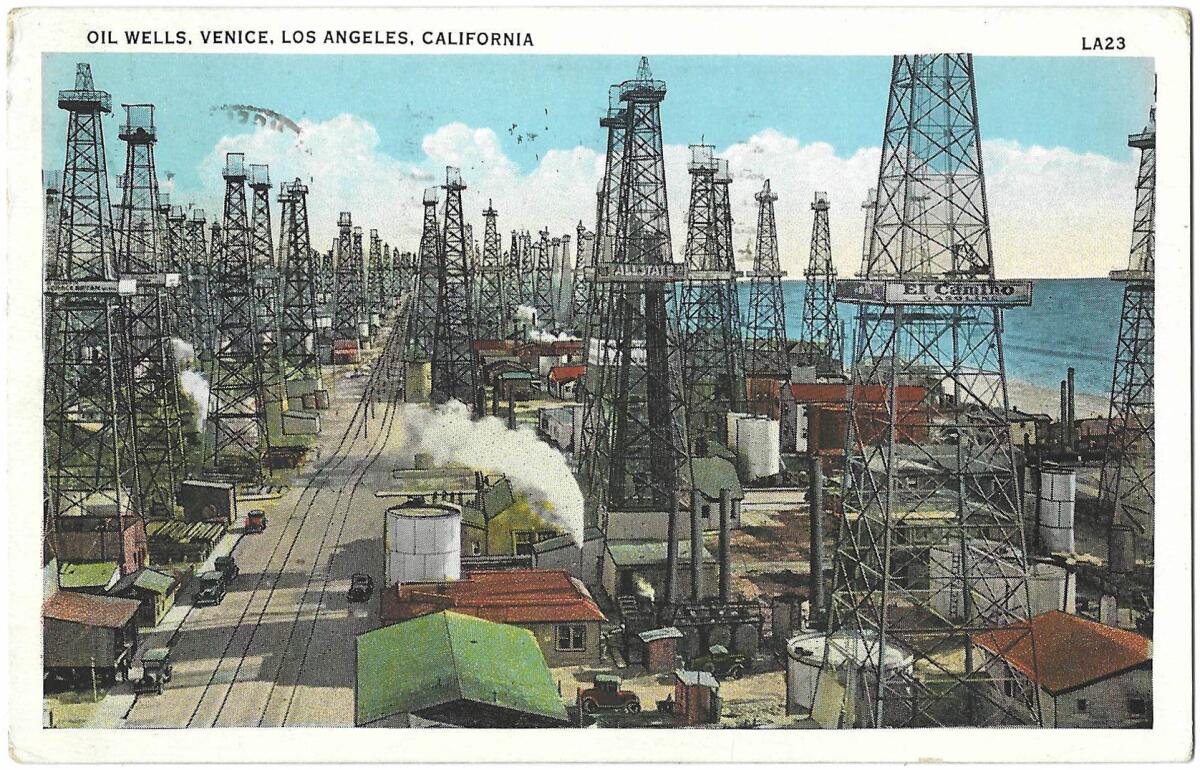

I’ve written previously about the oil and gas wells that dot Los Angeles, and the campaign for buffer zones to protect surrounding communities. But I still learned a lot from this column by The Times’ Patt Morrison on the local history of oil extraction.

Be sure to check out the selections from Patt’s vintage postcard collection, including the striking image of seaside Venice dominated by oil wells, which I’ve included above. Something to keep in mind next time you’re strolling down Abbot Kinney.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.