Newsletter: Will blackouts be Gavin Newsom’s downfall? A former governor weighs in

This is the Aug. 26, 2021, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

If you’re registered to vote in California, you’ve almost certainly received a recall ballot in the mail. The choice we face is whether to boot Gov. Gavin Newsom from office, and if so, who should lead the nation’s largest and most influential state.

Newsom has faced plenty of criticism from climate advocates for moving too slowly, as I’ve written previously. But if voters recall him, there’s a good chance the state would scale back its climate ambitions, perhaps dramatically.

The leading candidate to replace Newsom is conservative radio host Larry Elder, who at a recent debate promised to end the “war on oil and gas” and de-emphasize solar and wind power, as The Times’ James Rainey reports. Another top candidate, former San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer, helped pass the city’s first climate plan but earlier in his career lobbied for an auto industry group that questioned climate science, the San Francisco Chronicle’s Dustin Gardiner reports.

Then there’s John Cox, who lost to Newsom in 2018’s regular election after declaring that the state’s climate programs are “asking Californians to pay too much for too little.” The one semi-prominent Democratic candidate, YouTube personality Kevin Paffrath, says on his website that he supports “our green transition,” although he hasn’t talked much about the climate crisis.

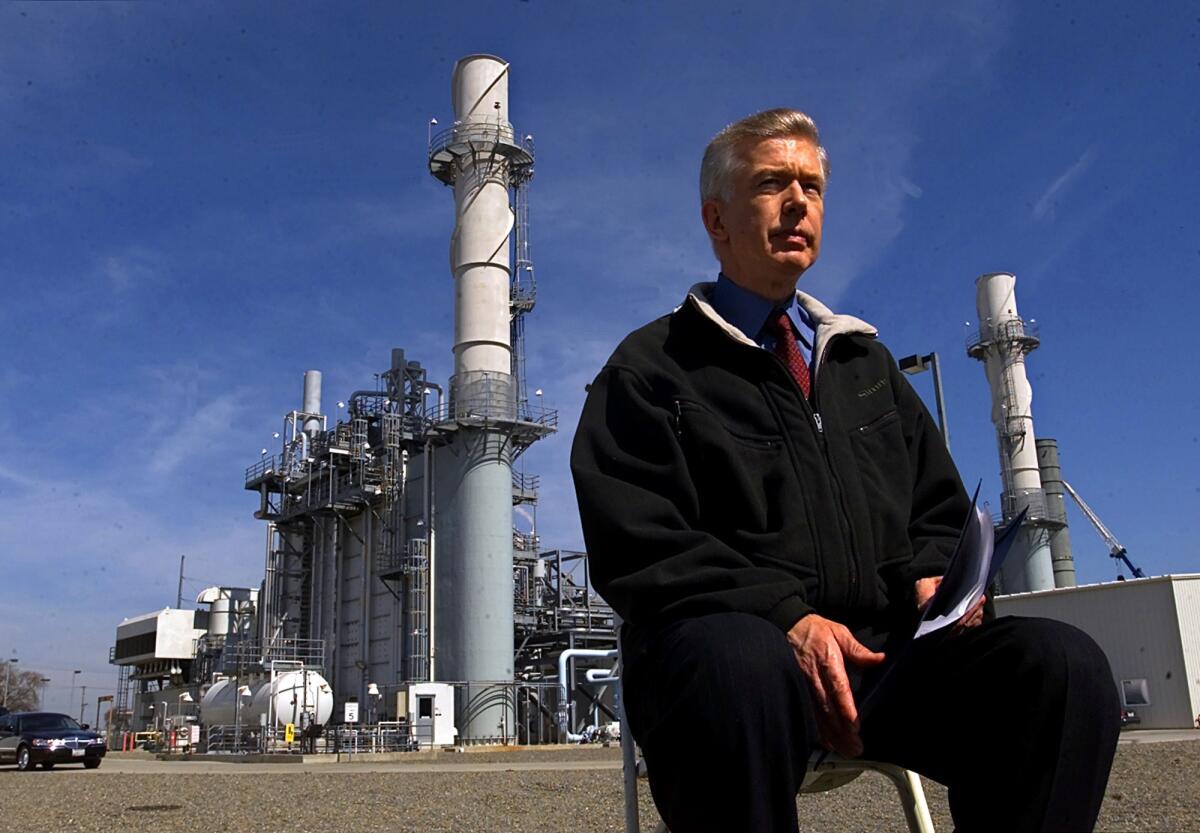

Will Newsom keep his job, and will the Golden State forge ahead on cutting emissions? I’m not much of a prognosticator, but I thought it would be interesting to talk with the only California governor previously voted out in a recall: Gray Davis.

I was especially curious to ask Davis about the early-2000s energy crisis, which was a major factor in voters replacing him with Arnold Schwarzenegger. I was only 8 years old in 2000, but I remember the constant TV ads urging conservation to help prevent blackouts. I remember walking around the house turning off all the lights, then proudly telling my parents what I had done.

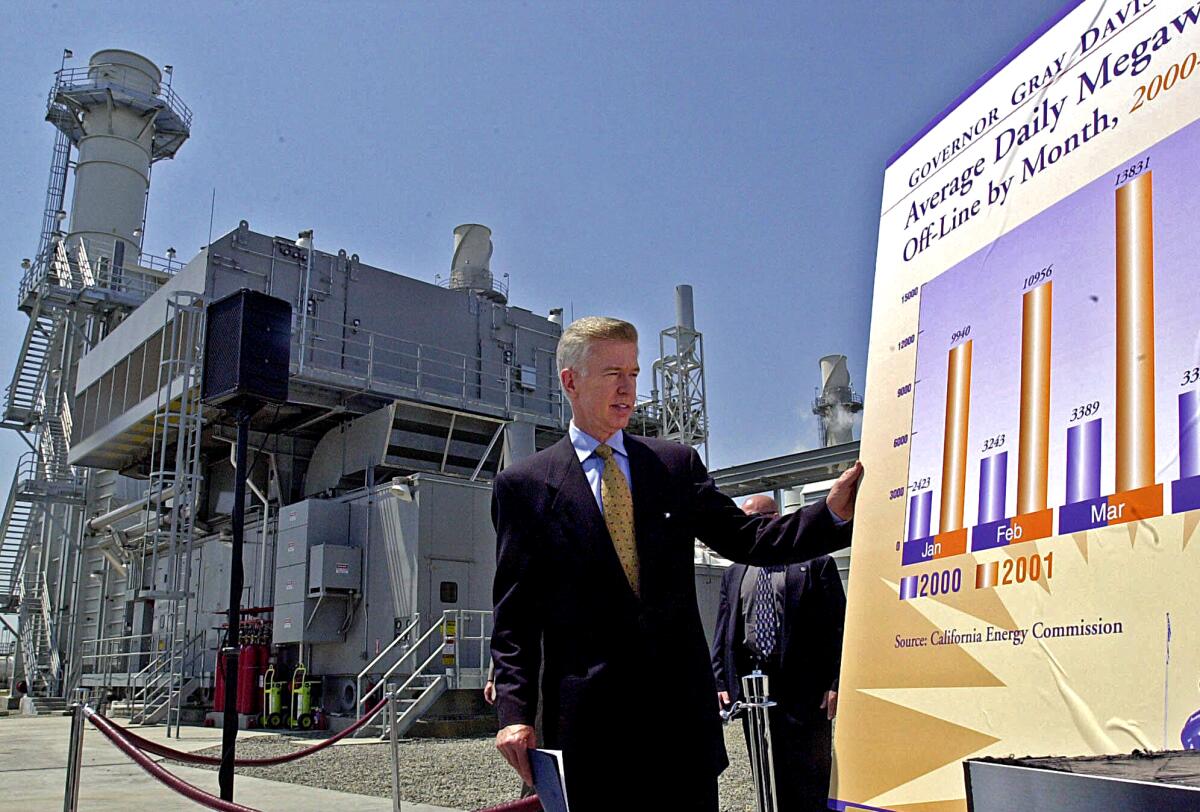

It turned out Enron and other corporate power traders were creating artificial shortages to drive profits, taking advantage of a poorly designed electricity market approved by the Legislature before Davis became governor.

Although market manipulation wasn’t the only cause of the blackouts, it was a big one, and a hidden one at first. Many details of Enron’s schemes weren’t known until after the recall election — and to some voters, they might not have mattered. Davis became the face of the crisis, the governor who couldn’t keep the lights on without begging people to turn some of them off.

And now Newsom is dealing with similar problems on the power grid. Last summer’s rolling blackouts didn’t affect as many people or last as long as the worst outages under Davis, but they highlighted the state’s failure to build enough clean power resources that can keep electricity flowing after sundown, when solar panels stop producing. Meanwhile, Pacific Gas & Electric is once again shutting off power to some customers in hopes of preventing its transmission lines from igniting wildfires.

Even when there aren’t blackouts, the threat isn’t far away, at least not at this time of year. State officials have already called six “Flex Alerts” this summer, and there’s no telling whether those pleas for conservation will cut it during the next heat wave.

Do California’s energy problems spell trouble for Newsom’s recall chances, much as they did for Davis? I asked the former governor what he thinks. The following highlights from our conversation are edited and condensed for clarity.

**

ME: Going into your governorship, did you have any concerns about this new electricity market you were inheriting?

DAVIS: When I was running for office, I had one or two briefings on energy regulation. The entire time I campaigned, not one individual — not a reporter, not a citizen — asked me one question about energy. So it was not top of mind.

I will note that the first deregulation bill, when it passed, was about as thick as an old phone book directory. And the only person who professed to understand what was in that bill was Steve Peace, Democrat from San Diego County. Not one person in either house voted “no”; it was a unanimous vote. So there was nothing to signal to me that this was controversial.

ME: How did it end up becoming such a crisis for you politically?

DAVIS: The problem became apparent to me sometime in 2000. Basically what happened is that Enron was nothing more than a criminal enterprise. They were a criminal enterprise, pure and simple. Their CEO was sentenced to 24 years in prison. The former CEO, Ken Lay, was convicted and died shortly thereafter. The CFO pled guilty to six years for hiding all the indebtedness.

But none of that was known until I left office. After I left office, tapes came out of Enron ordering that power plants be shut down to create blackouts. If I had just had those tapes, I think I could have won the recall. I got 45% of the vote as it was.

ME: What was it like for you, knowing that you couldn’t guarantee a reliable power supply in California?

DAVIS: You know, I don’t think we’d ever seen blackouts like this in my lifetime. It was a shocker. I remember having a call with Craig Barrett, who was the CEO of Intel, and four or five other CEOs from Silicon Valley, and they said, “Governor, you have to promise us the lights will never go out in Silicon Valley.” And I said, “There’s nothing I would rather do than give you that promise. But I don’t know what is causing this problem. Until I figure out what is the cause, I can’t make that promise.”

You come to expect the lights are going to be on. When they’re not on, it’s completely disorienting. And you just don’t want to go through that as a public official. There’s no explanation that’s satisfactory.

ME: How do you think Gov. Newsom is handling the blackout threat today?

DAVIS: I think he’s doing all the right things. Look at his emergency proclamation. He’s going to extraordinary steps to make sure we reduce demand. For example, all the ships that dock in Long Beach and L.A. and Oakland usually plug into the grid. Now they can run on backup generators. Does that create some pollution? Yes. But does that help keep the lights on? Almost certainly.

We need to go green in a way that is consistent with reliability. Too many people are plugged into machines that keep them alive at home. Schools, hospitals — all kinds of facilities need reliable power. As you go green, you have to err on the side of making sure there are no blackouts, because the quickest way to sabotage the acceptability of a 100% green grid is to have blackouts.

ME: Is it fair for voters to blame Newsom if the lights go off?

DAVIS: I’m going to quote from my graduation speech to Columbia Law School: “School is fair. Life is not. Just deal with it.”

I remember an L.A. Times cartoon on the editorial page, about a week before my recall vote. Two women are standing in the Pacific, and one says to the other, “Boy, it’s cold today.” And the other one says, “Yeah, that’s another thing I blame Gray Davis for.” So I mean, people don’t have to have a good reason to vote against you. They’re going to vote against you if they feel life is not getting better for them.

ME: There’s been a lot of talk about expanding “demand response” programs that pay households and businesses to use less power when the grid is stressed. What do you make of that idea?

DAVIS: Look it, we’re paying them to get vaccinated.

ME: If you were governor today, what else would you be doing to make sure we have enough electricity supply?

DAVIS: There’s enough power now to sustain us for many years, if we don’t just thumb our nose at every natural gas plant and say, “We should shut that off tomorrow.” If we do that, we’ll have blackouts.

But if we incent Silicon Valley and the investor community to find a way to greatly accelerate the expansion of battery storage, and incent even further demand response from large consumers and any people who are willing to take a reduction, that will hasten the day we can be all green.

**

Election day is Sept. 14. You can also vote by mail or drop your ballot in a neighborhood ballot box before then.

Here’s what else is happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

California lawmakers are finally starting to take sea level rise seriously. My colleague Rosanna Xia — who was a Pulitzer Prize finalist for her coverage of the rising Pacific — reports that several potentially helpful bills are moving toward passage in the Legislature. One would let local governments buy at-risk coastal properties and rent them out until they need to be demolished. Another would allocate $100 million per year for adaptation, plus additional funds for communities burdened by pollution.

More of Southern California has moved into the “exceptional drought” category. Details here from Melissa Hernandez; the latest drought map is not pretty, with most of the state bathed in red. The Times’ Priscella Vega wrote a moving story about how life changes when your well runs dry, focused on a San Joaquin Valley family that’s been forced not only to take shorter showers, but also to reuse wet paper towels and sell off beloved animals. Writing for the Atlantic, meanwhile, Mark Arax tells the haunting tale of a well-fixer confronting the reality that California’s farm country as we know it is unsustainable. And CalMatters’ Rachel Becker explains why the groundwater sustainability law the state passed seven years ago has done basically nothing to help so far.

As extreme heat becomes more common, picking crops is increasingly dangerous work. California has rules meant to protect farmworkers, but they aren’t always enforced — and workers are sometimes incentivized to keep quiet and overlook their own safety, as Miranda Green and Heidi de Marco report for Kaiser Health News, in a piece focused on Coachella Valley farmworkers.

THE WEST ON FIRE

More than 1.5 million acres have burned in California this year, with the worst part of fire season potentially yet to come. Los Angeles officials are urging residents to prepare by clearing brush around their homes, my colleagues Lila Seidman and Dakota Smith report. The worst blazes have struck Northern California so far, with the Caldor fire destroying at least 440 homes and choking the air around Lake Tahoe with hazardous smoke, The Times’ Alex Wigglesworth reports, and the Dixie fire becoming the second largest in the state’s recorded history. Here are our photographers’ most powerful images of the devastation.

Death, destruction and lung damage aren’t the only consequences of these climate-fueled infernos. The New York Times’ Winston Choi-Schagrin reports that fires this summer have burned through 150,000 acres of forests enrolled in California’s carbon-offset program, undermining the state’s efforts to fight climate change. Adding to the air quality woes, a new study by Stanford researchers finds that exposure to wildfire smoke increases the risk of premature birth, which can lead to health complications.

How can we limit fire damage, even as the planet warms? My colleagues Hayley Smith and Alex Wigglesworth have a nuanced story on the benefits and possible shortcomings of forest management techniques such as logging, thinning and prescribed burns. In Paradise, which was obliterated by the Camp fire, town officials are trying to buy out properties in risky locations and add park space that can serve as a buffer during future blazes, NPR’s Kirk Siegler reports. At the federal level, The Times’ Anna M. Phillips reports that the Pentagon has agreed to keep giving firefighters access to military satellite data, at least for another year.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

Like the Obama administration five years ago, the Biden administration is studying (but not pausing) the federal coal-leasing program. That means we’re seven months into Biden’s presidency and the federal government is still leasing coal, oil and gas on public lands, despite his campaign promises. The Washington Post’s Dino Grandoni and Steven Mufson report that the courts are playing a big role in these types of decisions, blocking some fossil fuel projects but requiring others to move forward.

Colorado Rep. Lauren Boebert didn’t disclose while campaigning last year that her husband had a lucrative consulting gig with a natural gas firm. Boebert is a fierce oil and gas supporter, the Washington Post’s Isaac Stanley-Becker notes. I’ve got the same question as Jonathan P. Thompson, posed in his Land Desk newsletter: “What the heck kind of consulting work did Jayson Boebert do for Terra Energy to rake in nearly a half-million bucks per year?” In other news involving far-right lawmakers who have fought conservation policies, WyoFile’s Angus M. Thuermer Jr. reports that climate-conscious outdoor retailer Patagonia will no longer supply a Jackson Hole ski resort after the owner hosted a fundraiser featuring Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene and Jim Jordan.

Critics say the infrastructure bill passed by the Senate would limit environmental reviews, potentially easing construction of oil and gas infrastructure even as it speeds clean energy development. Environmental justice advocates are worried about harm to disadvantaged communities, Dino Grandoni and Darryl Fears report for the Washington Post. The bill also includes more than $12 billion for carbon capture, the oil industry’s preferred climate solution, per Nicholas Kusnetz at Inside Climate News. But is there money for California’s bullet train? Maybe — it depends on whom you ask, The Times’ Ralph Vartabedian reports.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

The California National Guard plans to install 99 megawatts of solar power (plus batteries) at the only military airport in the L.A. area, in part to help support emergency response if an earthquake takes down the power grid. The solar microgrid could break ground next year, Daniel Langhorne reports for The Times. In San Diego County, meanwhile, officials approved a solar farm outside Jacumba Hot Springs over opposition from local residents, Rob Nikolewski reports for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

“The communities most at risk from air pollution and climate change are forced to bear the burden of the poor planning of the past.” Remember at the top of this newsletter, when former Gov. Gray Davis talked about Gavin Newsom doing whatever it takes to keep the lights on? Well, climate advocates are frustrated with Newsom for waiving pollution rules for diesel generators and gas plants, saying disadvantaged communities will suffer the most harm, Elizabeth McCarthy writes for Canary Media.

Electricity rates are going up for Southern California Edison customers, with an average bill increase of $12.41 per month. The Orange County Register’s Teri Sforza has the details. Much of the rate hike approved by the Public Utilities Commission will be spent on projects to limit the risk of wildfire ignitions. But some experts say the bill increase reveals a serious flaw in how the state pays for energy infrastructure, with low-income families facing the greatest burden of funding initiatives that benefit everyone.

ONE MORE THING

I couldn’t help but smile reading about nine high school students in Idaho who asked the legendary actor (and activist) Jane Fonda whether she’d pay for them to take a climate change course at Boise State University. To their surprise, she agreed — as long as they took action by delivering a Greenpeace petition to their congressperson, the Idaho Statesman’s Becca Savransky reports.

One of the students mused: “I’m sick of hearing climate change already. And we are not even to the worst of it yet.”

Truer words.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.