Charlie Smith’s ‘Men in Miami Hotels’ moves beyond the noir playbook

Perhaps my favorite moment in Charlie Smith’s terrific new novel, “Men in Miami Hotels,” comes not too far from the end. The protagonist, a Miami hoodlum named Cotland Sims, has snuck into Havana, on the run from a relentless line of gangsters who keep trying to kill him, as if his life had become an existential game of Whack-a-Mole. Cot is accompanied by Marcella, his longtime on-and-off girlfriend, who is traveling with an agenda of her own.

“You’re a real killer, baby,” he tells her, in a classic line from the noir novelist’s playbook — but just as we think we know where this is going, Smith turns it around on us.

“He felt — somehow felt — that what they were saying had been said a million times before,” he writes of his character, “as if the words had been scraped up from the grotty carpets of twenty-dollar bedrooms and second-run movie houses, and not even dusted off, not even looked at or sorted, used again. Old familiar scuds and wrake.”

That striking observation brings the author directly into the story by acknowledging that, yes, we all may recognize the conventions but there is something more beneath the surface, a self-conscious awareness of the roles life forces us to play. This, in turn, etches in stark relief one of the central tensions of the novel, which walks a line between genre and something considerably wilder, a fictional territory where a character might lose his or her soul.

Certainly, these are the stakes for which Cot is playing, even (or especially) if he doesn’t know exactly why. As the book opens, he steals a cache of emeralds from his employer, the brutal mob boss Albertson, only to lose this tainted treasure before the first chapter comes to a close. Albertson doesn’t care that Cot has no idea where the gems are; he wants his property back. As Cot tries to stay one step ahead, Albertson sends waves of killers in pursuit, first to Key West, where he has retreated to his mother’s Craftsman, and then to Miami and to Cuba, where the novel winds up in an unexpected, but inevitable, denouement.

More conventions? Yes, but Smith subverts them almost immediately, not least by creating a complex life for Cot. He may be on the run from mob assassins, but he is also, in the most specific sense imaginable, home, in the town where he grew up, attempting to help his mother, who is living in the crawl space under her house because the structure has been red-tagged after the most recent hurricane, and reestablishing his connection with Marcella and with his oldest friend from high school, a drag queen named CJ.

Everywhere he goes, people recognize him, from Marcella’s husband, Ordell, the county prosecutor, to the police themselves. “You can’t see a gangster,” Smith writes, describing Cot’s connection to this place, to these people, “without hearing about that at least once or twice a day: the dull, inevitable, unenviable stoniness. Yet a softness remains, supple, slowly undulating, a nexus like a jungle bridge flexing in breeze, a worry and substantiation, anchored in coral rock, humanness, spotty and reeking, still apparent — that’s another way of putting it — Hey, Sheriff, don’t you know me?”

As it turns out, such a question occupies the center of Smith’s story, which is less about crime than identity, despite the emerald theft and all those hit men seeking to take Cot down. Indeed, the novel’s violence, although pervasive, ends up feeling almost incidental; people fight or get shot with the matter-of-factness of shaking hands, and tense scenes (a kidnapping, a chase that leaves both cops and criminals dead on the Key West streets) dissipate almost without consequence, as Cot simply walks away.

It’s a strategy reminiscent, in some ways, of Elmore Leonard, who often treats brutality lightly, or Jim Thompson’s surreal 1958 chase novel “The Getaway.” But more to the point, Smith is operating in Denis Johnson territory, where narrative arises out of language, and scenes are important less for what happens in them than for how they are described.

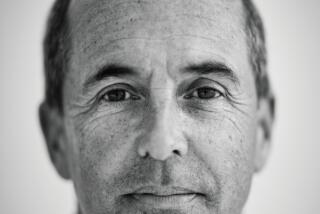

That makes sense, for like Johnson, Smith started as a poet; his seventh collection, “Word Comix,” came out in 2009. He has also written six previous works of fiction, including “Three Delays” (2010), which, like “Men in Miami Hotels,” unfolds in south Florida, and involves another ill-fated couple with a dodgy relationship to the law.

In this regard, it may make the most sense to read “Men in Miami Hotels” as an extended tone poem, in which the language of crime, of violence, informs the language of inner life. Cot, to be sure, is one complicated gangster, “making mistake after mistake … after taking the stones, after getting Albertson’s operative locked up, after running around here like he knew what he was doing, after putting his mother at risk, and Marcella too and who know who else … sticking his head in a noose. But it’s like he doesn’t care — or not that exactly: it’s as if he’s only half awake, only half there.”

That, of course, is how we lose ourselves, and yet, you don’t have to be a criminal to recognize the way Cot feels.

“It’s getting late,” Smith writes. “… He’s been thinking this for years. Sometimes you wake up and what’s capsized has righted itself. Sometimes the other way around. Hope like grease on your hands if you can even bear to hope. What a crock. Nobody can ever tell for sure what’s coming, he’s sure of that.”

Men in Miami Hotels

A Novel

Charlie Smith

HarperPerennial: 288 pp., $14.99 paper

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.