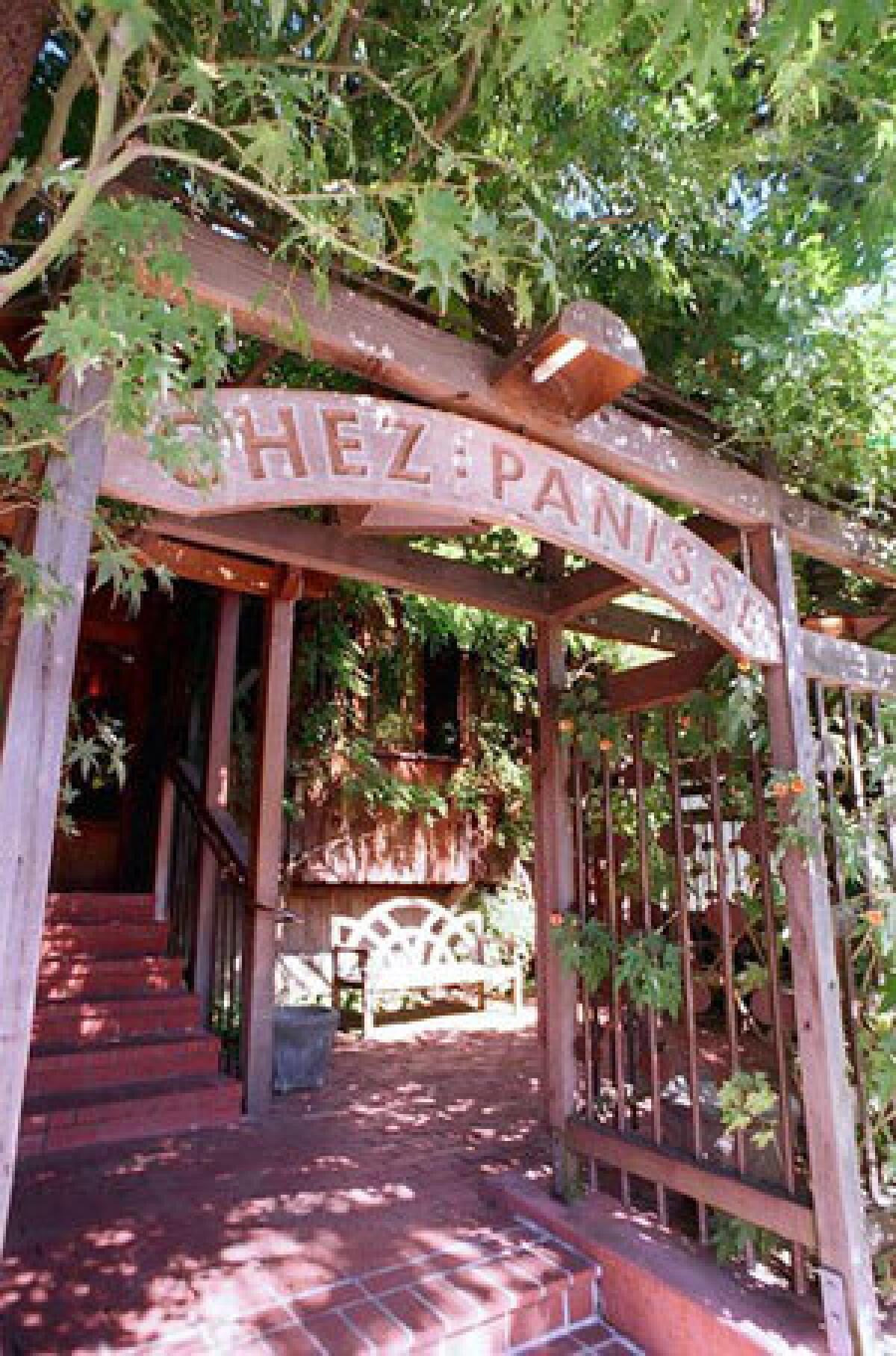

A Chez Panisse birthday remembrance

It was an obscure, dingy, two-story apartment building, converted from an old house, in an ignored part of Berkeley. Not expensive to buy. It had good bones. I tore it down to the studs and started to rebuild.

I was pretty much on my own, since Alice Waters, my 50-50 partner, was busy at her job at the Montessori school. Our backers, Berkeley lawyers, a special breed, had promised to be our partners, but a few weeks into the reconstruction they decided to pull out of the deal. That hurt us badly, since they had been our construction funding source.

Panicked, Alice and I scraped and begged for cash and managed to cobble together enough to keep going, as long as we did most of the work on an excruciatingly limited budget. We took loans of $300 or $400 from everyone we could, plus help from our families.

Maybe we would have had an easier time if we had been able to explain to them that 40 years on, this little place we were calling Chez Panisse would be regarded as one of the most important restaurants in the history of American dining. But even in Berkeley in the 1970s, that would have been a stretch. Still, this month, while most of the food world fetes the restaurant, it’s good to remember that its birth was far from painless.

I got involved in the restaurant because I had been dinner-party friends with Alice and her then-boyfriend, Tom Luddy. They asked me to join them as a partner and run the kitchen because, although Alice had a lot of ideas about food, she had never worked in a restaurant. Nor had I, but I was a talented amateur cook, giving large dinner parties for my academic colleagues, and relatively fearless about new ventures. But it turned out that cooking was only part of the overwhelming requirements of the start-up.

As city inspectors came by to examine the exposed rafters and struts, more and more requirements piled on me. They were sympathetic, but rules were rules. We had to re-plumb, rewire, shore up, fireproof. Every directive was a stab in the wallet.

Our plumber, a good guy but old, gimpy and not underweight, made an economical deal with us, but we could not afford to pay his assistant. So I enlisted a free assistant … me. In the mud in the cramped crawl space under the crumbling building, I learned to solder copper pipe. For me, covered with mud, lying on my back, torching the copper, this was a truly memorable moment in the Chez Panisse chronicles. And much more was to come, making the muddy condition an apt metaphor for the early pre-opening days.

Four carpenters and I worked on the construction job. I hammered and sawed with them. You might say the carpenters were hippies. They were talented but slow, taking time to enjoy the Berkeley version of coffee breaks on frequent occasions. Their pay was way below scale, but they got a home-cooked lunch on Fridays. They were a happy crew.

It was a tear-out-and-design-as-you-go project, with no documented plans, just a vision in my head.

As funds allowed, we finished the rooms. We even managed to keep the original toilets and staircase from the previous structure. I wanted to give the dining room a Provençal feeling. We put it downstairs, next to the kitchen, first, at my insistence, with a small window into the kitchen; now no wall at all. Our genius finish carpenter, Kip, back from two years in Japan studying Asian carpentry, made some brilliant cuts in cheap redwood bender board that gave the dining room a very elegant and French look.

Right off the farm

The hard-cash problems became even more serious. It was time to outfit the kitchen and dining rooms.

Unremarked in Chez Panisse history is the first direct-from-the-farm purchase. An advertisement in the San Francisco Chronicle sent me to Sonoma County, where a farmer had a barnful of used kitchen equipment. It is noteworthy what I had to avoid stepping in to get a look at the goods. (Not just mud.) Fact: The first farm-fresh purchase was a huge stove. We also got our refrigerator there.

Of course, when you buy equipment out of a barn, you never know what you’re getting. One of my most vivid memories of the early days was finding a large fetid puddle under a refrigeration unit that contained our precious food supply.

Outside, we put a face on the front of the building. Old doors were our cement forms to retain the planting dirt. My brother Charles, a Beverly Hills dentist, was the only guy I knew who could mortar bricks, and he came up to build the stairs and walkway into the building. Artist David Goines made us a sign in his brilliant style that morphed into menu headings, posters and our logo.

Alice shopped for chairs, tables, flatware — all used but perfect for the venue. And all cheap.

Now for the final problem — the cuisine. We aimed for bistro-trattoria food, and I convinced Alice that our best shot was a single menu that changed every day. This turned out to be a great stroke, since we published monthly schedules of our dishes, again beautifully designed by Goines. People would put them up on refrigerator doors and mark days and dishes that they wished to try. We offered things that could not be found then in American restaurants, such as coq au vin, cassoulet, pasta fresca and pâté.

Since many Berkeleyites had passed our construction site, our presence and opening were well known. We were triple-booked the first night, and the restaurant has been fully booked for the last 40 years.

None of us had ever been in the restaurant business, except as an occasional waiter. The first days were furious, with Jerry flitting around the dining room, Vicky and Leslie jamming at the stoves, and Alice glowing with excitement. I was in charge of the kitchen, acting as chef de cuisine due to my extensive knowledge of French and Italian cooking, and Alice was “front of house.”

Somehow, we did it.

Five years later, I moved to Los Angeles to produce films and sold out my half of the restaurant. But I am grateful that I had the opportunity to participate in the creation of a legend.

Happy birthday, Chez Panisse. Out of the mud grows the lotus.

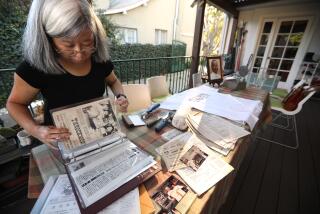

Paul Aratow is the author of “La Bonne Cuisine de Madame E. Saint-Ange.” He is a film producer living in Los Angeles.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.