Chef John Sedlar returns with lots of irons in the fire

Last week, chef John Sedlar celebrated the 30th anniversary of his seminal, erstwhile restaurant Saint Estèphe with a sparkly cocktail party and an elaborate tasting menu for a select group of admirers who remember the go-go ‘80s and his particular mark on American cuisine — the birth of modern Southwest cooking. As Sedlar recalls the era, “It was a time!”

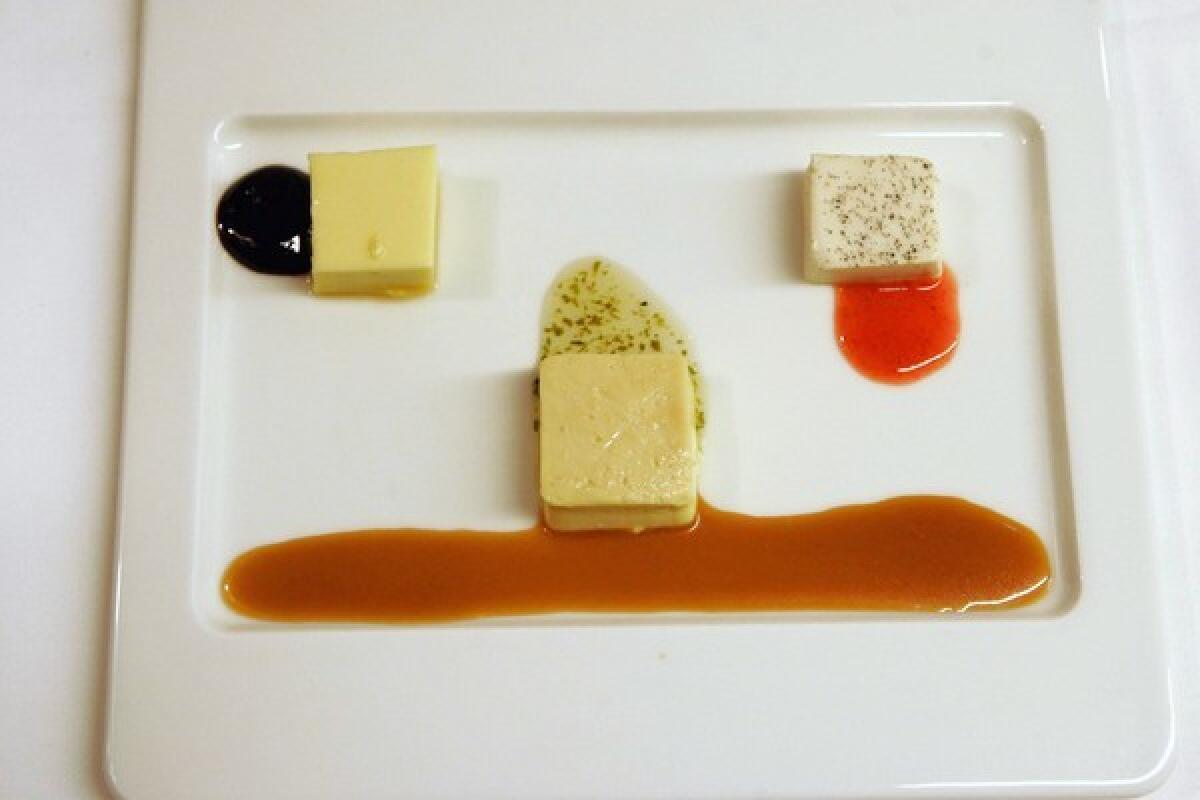

A time when goat cheese just started showing up on menus, fusion wasn’t considered an “f word” and Sedlar’s plating was as iconic as a Factory Records album sleeve. “He was practically the first guy to do the drizzle on a plate!” says designer Eddie Sotto, one of Sedlar’s business partners, who attended the Gruet-fueled fête.

But the party at Rivera, Sedlar’s 2-year-old downtown Latin restaurant, commemorated another return for the man of the hour: the rare chef comeback. In his case, after a few long-gone restaurants and a hiatus that lasted a decade and a half.

Times restaurant critic S. Irene Virbila gave Rivera 31/2 stars and called it “one of the most exciting restaurants to debut in L.A. in the last few years” from a “hyper-talented chef [who] nailed it every time.” (Only two restaurants in Los Angeles, including Rivera, have earned that rank.)

“There aren’t a lot of chefs who could drop out for such a long time and then come back with such force,” says Mary Sue Milliken, who with Susan Feniger opened City Café (later it would become Border Grill) on Melrose Avenue at about the same time that Sedlar opened Saint Estèphe in Manhattan Beach. “This industry is so competitive and so hard…. John’s one of those people who has a contagious passion and persistence.”

And Rivera was just the start. This year, Sedlar, 56, opened another restaurant, Playa on Beverly Boulevard, and still pursues a decades-long dream to build a museum dedicated to Latin cuisine — an obsession partly inspired by a Day of the Dead tamal he tried on a trip to Lake Pàtzcuaro in Mexico.

“I was terrified,” says Sedlar of opening Rivera. “It was very, very scary. Why would I try to do a restaurant again and compete with all the talent in this city? …. I was scared my food would be dated.”

Before blue corn tortilla chips and chile-infused chocolate were ubiquitous, Sedlar was serving blue corn tortillas with caviar and chocolate chile relleno at Saint Estèphe. “No one had ever seen a tortilla in a white tablecloth setting,” says Sedlar, who was born in Santa Fe, N.M., moved to Los Angeles in 1973 and cooked with legendary chef Jean Bertranou at the French dining institution l’Ermitage.

Sedlar, along with chefs such as Mark Miller of Coyote Cafe in Santa Fe and Stephen Pyles in Dallas, was at the forefront of a movement to embrace regional American cuisine. Other chefs in their circle included Robert Del Grande and Dean Fearing. “The five of us built this game,” Sedlar says. “We’d started to ask ourselves, what is American food? Why are we such Europhiles?”

He and his then business partner Steve Garcia had opened Saint Estèphe in a South Bay mall next to a dry cleaner in late 1980, “a nice French restaurant” (named after a celebratory bottle of 1953 Cos d’Estournel from the Saint-Estephe region in Bordeaux). But “it needed a bit of a spark,” Sedlar says. After a visit home to New Mexico, he returned to L.A. with 15 cases of red Chimayo chiles and started experimenting. “I integrated them in every item on the menu. Ice cream, pickles, chutneys, sauces, apps, entrees, all courses of the menu.

“I worked with my grandmother in search of the perfect tortilla. We held them up in our hands, took pictures, studied the shape of them, the char marks.”

The chiles, beans, spices, herbs, seeds, pine nuts, squashes and corn of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains worked their way into French dishes such as salmon mousse tamale, duck liver mousse with pickled chiles in aspic, posole consommé with foie gras and truffle. The menu was written entirely in French: tamale de mousse de saumon, cuit à la vapeur dans une gousse de maïs, nixtamal, beurre au cilantro; soufflé aux chiles verts; crêpes de maïs bleu. Who knew the French word for tumbleweed? (It’s “squelette,” according to a menu.)

“When he first put dishes such as ravioli stuffed with carne adobada in a chevre sauce on his menu, most of his customers thought he was insane,” wrote then L.A. Times restaurant critic Ruth Reichl in 1991. “Ten years later his French-inflected Southwestern menu seems not only sane but downright sensible: Sedlar’s dishes are uniquely his own…. I am particularly fond of this gorgeously simple slice of steamed salmon in three sauces that looks like a Navaho sand painting.”

The way Sedlar sees it, he didn’t change as a chef from Saint Estèphe to Rivera. “The customers changed; they want to be challenged. They became flavor seekers … grab-you-by-the-throat flavors — sharp chiles, deep herbaceousness, bright citrus hits. Latin dining rose to the occasion.”

Though his plating is still visually arresting, it’s more streamlined and contemporary — no smoked salmon molded into the shape of a rattlesnake or flowers carved from jicama. Sedlar is revisiting those dishes with a special Saint Estèphe menu at Rivera this month.

By the early ‘90s, Sedlar decided to move on from Saint Estèphe and sold his shares. In 1992 he opened Bikini on 5th Street in Santa Monica with new partners. The name evoked “a stylish frame of mind, healthy, youthful, vibrant, fresh,” Sedlar says. “There were big windows facing Santa Monica sunsets. It was the California Riviera.”

Bikini was ambitious, and the next couple of years would prove it was overly so. The restaurant had a two-story glass facade, two kitchens, an Eric Orr waterfall sculpture, terrazzo floors and bar. A sign above the bar said “Chateau d’Yquem on tap” (for $40 a glass), and there were several sets of custom tableware — some painted with the words “Blam Blam” à la Roy Lichtenstein, others depicting the virgin of Guadalupe. Sedlar now refers to Bikini as “Rivera, exploded.”

The menu included some of Sedlar’s familiar, deft nouvelle Southwest cooking but also some dishes that confounded, such as pumpkin-seed-encrusted whitefish schnitzel with spaetzle and duck egg foo yong.

Amid a recession, Bikini fizzled — though Sedlar had reached celebrity-chef status (complete with a line of truffle-scented hair care products) — and became Abiquiu, a lower-priced, more-casual restaurant. But Abiquiu never fully recovered from the hit of the Northridge earthquake in January 1994. As one L.A. Times column read, “the beach party” was over.

“I didn’t plan on leaving the business,” Sedlar says. “Restaurants and chefs have to wear so many hats. It’s a very intense 24/7 life…. After the earthquake happened, I decided take a few months [off], and it turned into 15 years.

“I didn’t disappear. I was doing other things. I did exactly what I wanted to do.”

In the years after Bikini and Abiquiu closed, Sedlar consulted for restaurants and corporations, started his own line of gourmet tamales and traveled throughout Central and South America — 20 to 25 trips that were research for his museum. Meanwhile, Sedlar, designer Sotto and Rivera partner Bill Chait, who founded the Louise’s Trattoria chain, talked on and off for several years about opening a restaurant.

“I missed the experience of cooking for people,” says Sedlar. He says he returned to restaurants not humbled but “more reserved.”

“John was more worried than I was” about his food, says Chait, who has been friends with Sedlar since his Bikini days. “It’s very contemporary food with his visual style. Now it’s unusual, but it’s very ‘80s.” In a town where and at a time when it’s all about casual presentation, Sedlar’s plates — stenciled with spices or decorated with photographs under a plate of glass — stand out.

And though the more-than-$2-million Rivera opened in the middle of the recession, Chait, also a majority partner in Playa, says both restaurants have been “very, very successful.

“We had planned [Rivera] before [the recession] hit. We thought we were heading into halcyon days,” Chait says. “It’s not a fine-dining restaurant, but it is chef-style dining. John adjusted the menu” when it became apparent that the economy wasn’t going to support fine dining.

Sedlar says he has plans for “a top-notch, stellar Latin restaurant” in the museum he refers to as the Museum Tamal, a center for Latin culinary arts and history. Walking through the 4,800-square-foot temporary headquarters on Hope Street, he says, “we need 20 of these, no less.”

It would be quixotic if he weren’t tenacious enough to have already culled sponsorships from food companies, doggedly and meticulously collected and organized exhibits, and negotiated gallery spaces throughout the city for temporary shows such as “Five Centuries of Cuisine in L.A.” or “Comidas Prehispanicas.”

“I’ve also had a fantasy to open a Latin restaurant in Paris. I think they would love it. Being French-trained, for me, it would be a full circle.” Again.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.