At José Andrés’ $235-per-person Somni, inventive Spanish cooking — and an acting coach

Chef Thomas Keller once invited a ballerina to his three-Michelin-starred Per Se in New York to teach the servers about physicality and grace, and how precise body awareness was critical in helping an elite dining room run smoothly.

The general manager at Somni, a similarly ambitious $235 tasting menu restaurant near the Beverly Center, liked the idea.

But this is Los Angeles. So the restaurant hired an acting coach.

That explains why Somni’s chefs and line cooks, a dozen in all, could be found staggering around a small conference room on a February afternoon, a few weeks before the restaurant was scheduled to open. Some flapped imaginary wings, others walked with a limp, before reciting in exaggerated British accents: “Betty Botta bought a bit of bitter butter; a bit of bitter butter did Betty Botta buy.”

Under the direction of actor Gregory Mangieri, they were coached through a series of exercises usually reserved for the stage and not the kitchen: vocal warm-ups, tongue twisters, movement drills and mental focus and clarity training.

The point of the session was to help the chefs and cooks feel comfortable in front of an audience — because once Somni opened in March, they would be literally front and center, every night.

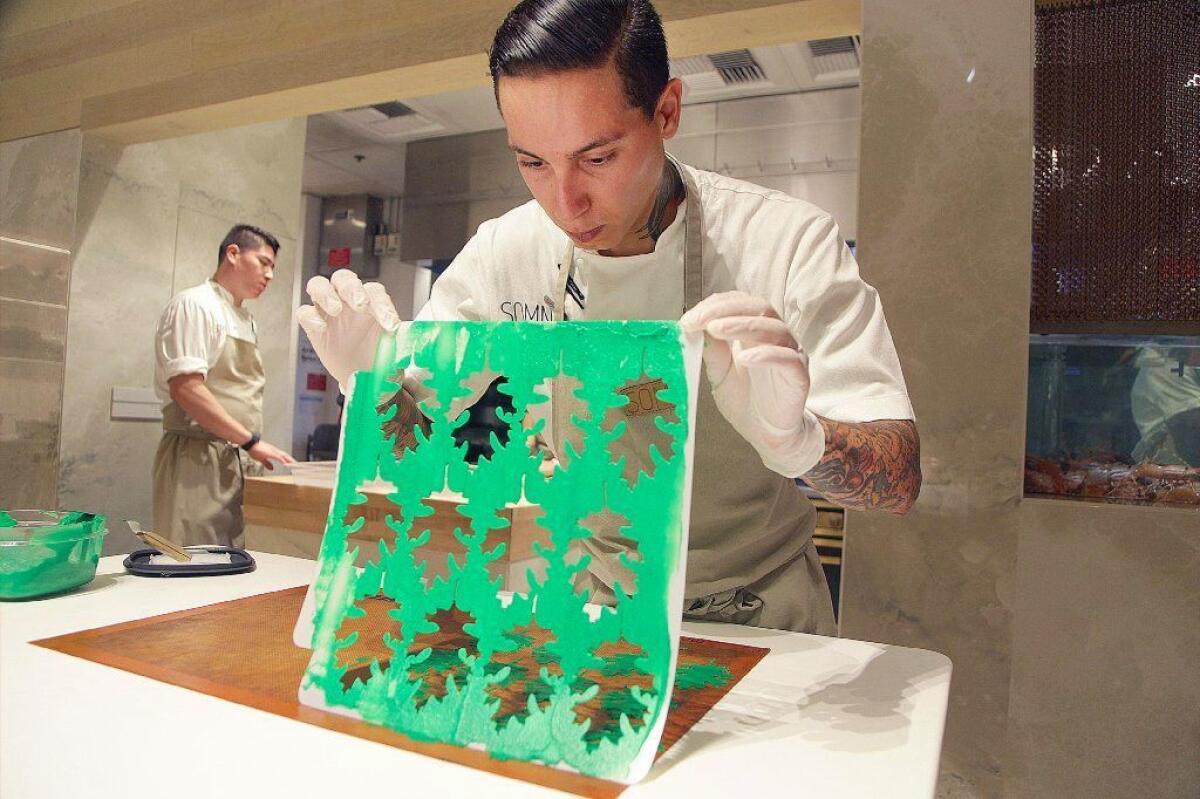

At José Andrés’ and Aitor Zabala’s Spanish-influenced Somni, which means “dream” in Catalan and replaces the former Saam inside the SLS Beverly Hills hotel, there are no servers. So in addition to cooking and plating, the chefs are responsible for almost all guest interaction: dropping off dishes, reciting the ingredients and complicated preparation methods that make up each of the more than 20 courses, and providing guidance on how to consume them.

Because the restaurant also has no tables — just an arching, semicircular counter — guests sit side by side, facing the cooks as they work in a softly illuminated open kitchen. The dining room itself is intimate, windowless and hushed, a curved wall sloping to meet the ceiling and floor. It isn’t a theater, but it feels a bit like one.

“There’s no separation, there’s no dividing wall. It’s really about the chefs being in front and taking their center stage,” said Eric Jeffay, Somni’s general manager. “We try and flesh out this experience as much as possible.”

To describe a dining experience as theatrical might bring to mind campy dinner-with-a-show Vegas productions, which Somni is not. But you do buy tickets in advance instead of making a reservation and receive a playbill-esque menu with the names of the entire kitchen staff at the end. And there are elements of drama woven through the night.

To get to Somni, you have to walk through the Bazaar restaurant, an over-the-top, whimsical space that previously housed a tarot card reader and a caricature artist in its early days. When you enter Somni’s dining room, the first thing that catches your eye will probably be the wooden mannequin hands propped upright on a table (the hands will be topped later with a generous glob of caviar, a play on the “caviar bump” typically served on a diner’s fist).

And similar to watching a play, diners at Somni progress through the two-and-a-half-hour meal in unison. Ten plates hit the counter at the same instant and everyone eats in sync — essentially, a tightly choreographed dinner party for 10 people executed twice a night (seatings are at 6 and 8:30 p.m.).

At most restaurants, servers announce dishes tableside, and parties dine at their own pace. Here, the introduction of each dish is the hallmark of the Somni experience, “almost like a wow factor,” cook Luca Dai Pra said.

Each course begins with a flourish as a single chef or cook — they take turns, with each responsible for presenting a couple of dishes — breaks from the pack, strides confidently to the center of the room and pivots to face the audience.

“Everything stops for one second and everybody’s attention is towards the cook,” Dai Pra said.

There might be a pause, a wide smile, an outstretching or clasping of the hands before the cook launches into a soliloquy of sorts:

“With this dish, we are going to make another stop in Spain,” one says, by way of introducing a course with ham and a modernist take on “beans.” “A quintessential Spanish ingredient, jamón ibérico, we have it in the broth; it’s also in the beans. They’re very fragile, and they may burst on you.”

Some incorporate gestures to amp up the showmanship: “I recommend breaking apart the head and sucking the juices,” one cook says of a glistening Santa Barbara spot prawn, holding his hands aloft and mimicking a twisting motion.

Whereas diners typically whip out their smartphones to take photos of their food, here, some direct their screens at the speaker.

That cooks are replacing servers in high-end restaurants is not new — the model is also used at Scratch Bar in Encino and Le Comptoir in Koreatown, among others; anyone who has ordered omakase will be familiar with a chef placing sushi straight on a diner’s plate.

Even restaurants that still have servers are giving diners more face time with prominent chefs — at Vespertine in Culver City, for instance, Jordan Kahn greets every guest at the beginning of the meal with a bow and a short introduction. The chef-forward format gives guests direct access to the people crafting their food — a selling point at exclusive restaurants all vying to distinguish themselves from one another.

These sorts of intimate interactions are more doable in places that serve just a handful of people each night, as Somni does. But that doesn’t mean all chefs are at ease in front of a crowd, no matter how small.

“Not too many cooks have been in that position in their career,” Zabala said. So the restaurant was receptive to “anything that would help people be less scared, and more approachable to guests.”

That’s why Mangieri, a 27-year-old actor who recently moved to L.A. from New York, was brought in. This was an unusual gig, one he landed because he and Jeffay knew each other from middle school.

Mangieri had taught acting before, but never to chefs. Having worked in various front-of-house positions at restaurants himself — he is an actor, after all — he maintains that acting and cooking are more similar than one might think.

He said his intention with the one-time, half-day training session was “taking what an actor does and applying it to a kitchen setting.”

During the class, Mangieri began by asking the cooks to spread out and walk forward, backward and side to side — when two would invariably cross paths, they would engage in a brief conversation before smoothly sidestepping one another.

He conceded that some were “less willing to be goofy,” but he applauded the cooks overall, noting how far out of their comfort zones acting was.

“A lot of times, that’s not something that a chef wants to do — they don’t want to be in front of guests, they don’t want to have to talk to people,” he said. “They like being in the kitchen, they’re cooking the food, they are behind the scenes. Kudos to them for even wanting to do it and having the courage to be doing something different.”

Besides teaching them to be aware of their surroundings, Mangieri wanted to inject a sense of playfulness into the session and instructed the cooks to pretend they were very large or very small, to speak loudly and then softly, and to take on different characters.

“In the beginning, when he told us to say those things, I felt silly. I was like, ‘I don’t know, around these people I’ve barely met? They’re going to make fun of me,’” recalled Dai Pra, who previously worked at San Francisco’s Saison and Atelier Crenn.

“But then we were all doing it together, you know? You start to lose that feeling of silliness and you start having more fun.”

The lessons, he said, carried over into the Somni kitchen, helping him feel more confident, even with “literally 20 eyeballs staring at you at all times.”

“If we’re all uptight and scared, it’s going to change the experience of the guests,” he said. “But if we’re feeling comfortable and having a good time, I feel like then the guests will feel the same way.”

465 S. La Cienega Blvd., Los Angeles, (310) 246-5543, www.exploretock.com/somni/.

Twitter: @byandreachang

Instagram: @byandreachang

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.