Students’ progress stalls on California’s standardized tests

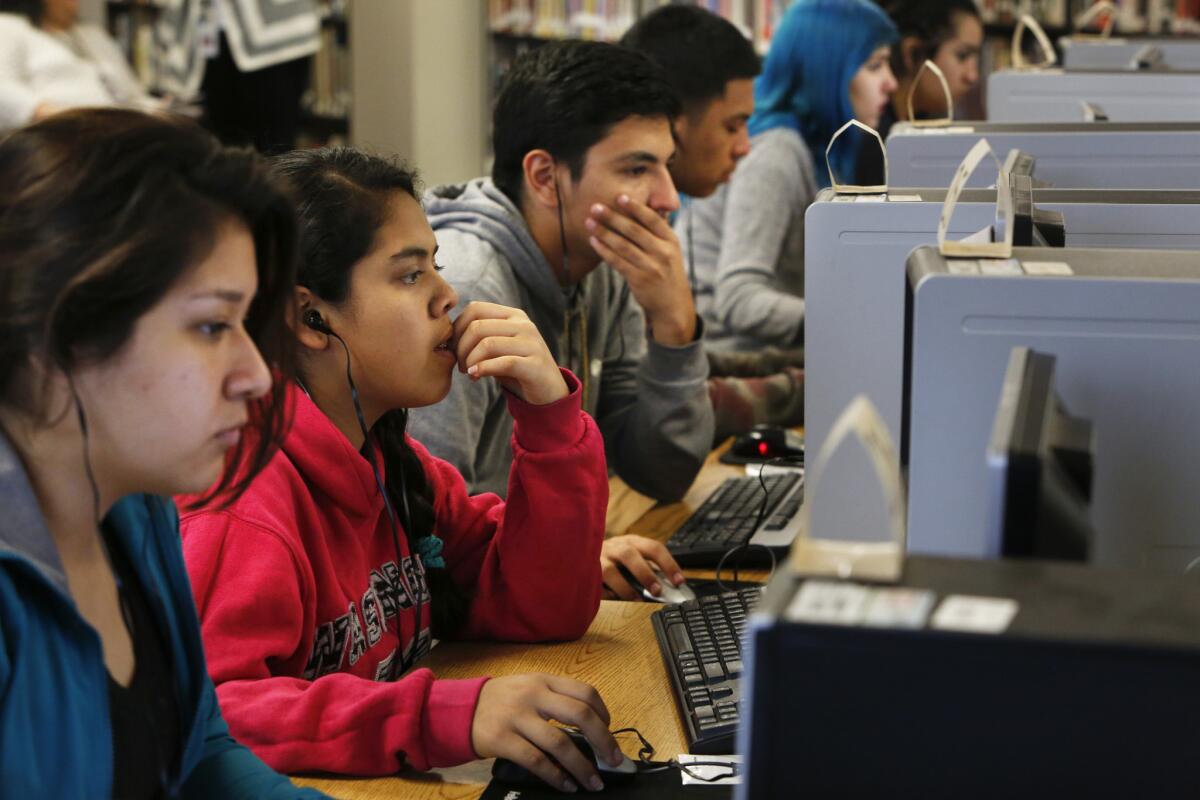

When California rolled out new standardized tests, experts said scores would improve when students got used to them. But three tests in, rather than showing strides from familiarity, their scores have stagnated — essentially flatlining in English and math.

About 3.2 million students in third through eighth grade and 11th grade took the tests in the spring. This year, 49% passed the English exam, compared with 48% in 2016. In math, 38% of students met or exceeded the state’s standard, compared with 37% last year. Fifth graders’ scores dropped slightly in English.

The previous year, students’ scores had improved in both subjects, prompting California’s State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson to travel from Sacramento to Los Angeles and hold a news conference to highlight the gains.

This year, state officials delayed releasing the scores for a month, citing problems with the data. Torlakson issued a statement describing the results as sustained progress.

“I’m pleased we retained our gains, but we have much more work to do,” he said.

In 2015, the first year of California’s experimentation with the new exams, 44% of students met the English benchmarks, and 34% did so in math.

“I’m not surprised they’re flat,” Gregory Cizek, a testing expert at the University of North Carolina, said of the California results.

Cizek was a technical advisor for the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium, which developed the California tests.

In the past, he said, when states adopted new standardized exams, students’ scores increased as they and their teachers became accustomed to the format and questions. But he described the California tests as a “different animal.”

“They’re requiring changes in classrooms to get gains,” he said. “You’re not going to budge this needle much if fundamentally the way kids are being taught doesn’t change.”

Statewide, there continued to be a dramatic gap between black and Latino students’ test scores and those of their white peers — a gap that civil rights groups point to as an illustration of troubling disparities in the quality of education.

Like their classmates, black and Latino students’ English scores were basically the same as last year. In math, they posted a slight gain of about 1 percentage point. Still, only 19% of black students hit math benchmarks.

“Saying equity 10 times in a row doesn’t mean you actually care about it,” said Ryan Smith, executive director of The Education Trust-West, an Oakland-based nonprofit focused on educational equity. “The state can’t say it’s committed to equity without having results and actions to prove it.”

Students in the Los Angeles Unified School District also posted flat scores in English and math and continued to lag behind their peers statewide.

This year, 40% of district students met or exceeded the state standard in English, compared with 39% in 2016. About 30% of district students passed the state’s math exam, compared with 29% last year.

“It’s moving in the right direction, but we’re not completely satisfied with the increase,” said Oscar Lafarga, executive director of the district’s Office of Data and Accountability.

The tests are based on a relatively new set of learning standards called the Common Core, which are supposed to be more rigorous and more indicative of how prepared students are for life beyond high school.

The scores are much lower than those on California’s previous standardized tests, because the tests are harder. In order to meet the benchmarks, students need to demonstrate not just proficiency but mastery.

The state delayed the public release of the scores by nearly a month, though schools and parents got access to their individual scores in the summer. California Department of Education spokespeople attributed the lag to a difficulty tying the scores of 25,000 San Diego special-education students with their appropriate school districts.

These days, education experts nationwide, and particularly in California, are trying to de-emphasize test scores, arguing that a previous generation’s reliance on test scores when judging schools contributed to punitive environments and encouraged schools to teach to the test, at the expense of enriching students’ lives and increasing their desire to learn.

California has now veered in another direction, away from cold numbers, translating test scores into colors and presenting them with numerous other color-coded measures of school success on the California School Dashboard, a new digital school grading tool.

The dashboard is supposed to ultimately form the backbone of the state’s system for identifying and helping underperforming schools improve. But some State Board of Education members say the board showed a lack of urgency about narrowing the racial achievement gap in designing the system, in part because schools can be failing certain groups of students but still appear to have average or high academic ratings.

Samantha Tran, senior managing director of education policy for Children Now, a group that lobbies and organizes activists on children’s issues, said she is worried that the stagnation in test scores means the dashboard will put many schools on yellow — the color corresponding to neutral, or average, for academics. “We’re going to see a lot of yellows when our most high-needs kids are far behind,” she said.

While standardized testing remains controversial in other states, California officials say they went to lengths to introduce the new tests carefully in a way that made their meaning clearer to parents. Torlakson praised the state’s high participation rates, saying that they showcase “The California Way,” a catchphrase State Board of Education members have used in describing the state’s reduced emphasis on testing and new accountability system. Less than 1% of students opted out of the test due to a parental exemption.

Data Editor Ben Welsh contributed to this story.

ALSO

L.A. Board of Education chooses Monica Garcia as new president to replace Rodriguez

L.A. County to investigate public school system’s enrollment of Catholic school students

Settlement will send $151 million to 50 L.A. schools over the next three years

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.