Advisors work to freeze ‘summer melt,’ get students to college

JanicaRose Buensuceso had planned to leave Orange County and attend college at Cal State East Bay in Northern California. Then family and financial problems emerged in the weeks after she graduated from Los Amigos High School, making the move increasingly difficult.

As the summer wound down, the 17-year-old from Fountain Valley thought about skipping college for a year and working. But she also worried that if she got out of study habits, it would be hard to return and she might never finish college, she said.

She was at risk of becoming an extra statistic in what experts call “Summer Melt.” That term refers to the substantial, but often invisible, group of usually low-income students who intend to start college and even send deposits to enroll but are stymied by personal and financial issues in the weeks before classes begin. Their situation is made worse by their families’ lack of experience with college bureaucracy.

It is a group that is now receiving a lot more attention in academia — and more help tailored to them. Some of that assistance involves technology, such as sending text messages reminding students of class registration deadlines, and some requires increased personal interaction, such as mounting last-minute appeals to improve financial aid grants.

Researchers focusing on summer melt estimate that between 10% and 30% of students from some urban high schools who register for colleges wind up not starting fall classes at those campuses. That occurs even though many are headed to low-tuition community colleges.

The summer is a “vulnerable time” for those students, said Lindsay C. Page, coauthor of “Summer Melt,” a book about the issue being published by Harvard Education Press this month. High school counseling is usually not available after graduation and students often are not yet connected to college services, even as colleges want summer payments and decisions, said Page, an assistant professor of education at the University of Pittsburgh.

Plus, those students often are the first in their families to attempt college, she said. While motivated to help, parents may be unable or too intimidated to push them over summer hurdles such as placement tests, health insurance requirements and dorm arrangements.

The students at risk of melting usually “have done everything that school and society have asked of them. They’ve done well enough in high school and followed the steps from A to Y,” said Benjamin L. Castleman, the book’s coauthor. It is important to help those students “who’ve come so far, and in whom we’ve invested so much, to realize their college aspirations,” said Castleman, who is an assistant professor of education and public policy at the University of Virginia.

His research shows that such help can reduce the melt by as much as 20%. As a result, programs are being started across California and the nation to give students a hand in the summer.

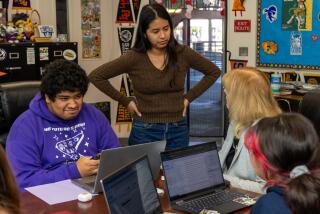

For example, Buensuceso received help from the Southern California College Advising Corps, a nonprofit organization run by USC and affiliated with a national outreach effort. The Corps staff working in her high school researched deadlines for financial forms, tuition payments, enrollment orientations, transcripts, housing and testing at scores of colleges. Then the appropriate text reminders were sent to 249 recent Los Amigos High graduates who planned to attend the colleges, said Davis Vo, an advisor at the school. Some students received as many as 10 texts during the summer, he said.

If students are the first in their families to attempt college, all the paperwork and registrations “can be overwhelming,” Vo said. But given some guidance, they usually can do it themselves in future semesters and help younger relatives and friends. “It is building a college-going culture,” he said.

While the text messages by themselves may not have prevented “melts” this summer, Vo said the overall extra attention increased college enrollment. In some cases, that meant a last-minute switch from a distant four-year campus to a two-year community college closer to home.

With the help, Buensuceso got refunds from Cal State East Bay and recently began classes, if barely in time, at Santa Ana College. Starting college without delay, even at a campus she initially overlooked, “is going to help me out more career-wise and education-wise.” She now hopes to transfer in two years to a Cal State in Southern California and possibly become a physical therapist.

Many community colleges don’t have the resources to track down missing students or wrongly assume they decided to enroll elsewhere, said Alexandra Chewning, vice president of research and evaluation for uAspire, a Boston-based organization that pioneered some effective anti-melt campaigns. The group’s counselors learned that some students do not have computers at home and lack Internet access in the summer to receive colleges’ emails. So uAspire began the phone text-messaging effort in 2012 and this summer reached 3,175 students in Massachusetts and Florida about deadlines and other issues, she said. With a new office in San Francisco, Northern California students will be added this year.

Ensuring that new students are not late with tuition payments and fees is especially important, Chewning said. Some panic if levied with late fees and drop out. “Because of lack of communication and lack of awareness, some students don’t go to college,” Chewning said.

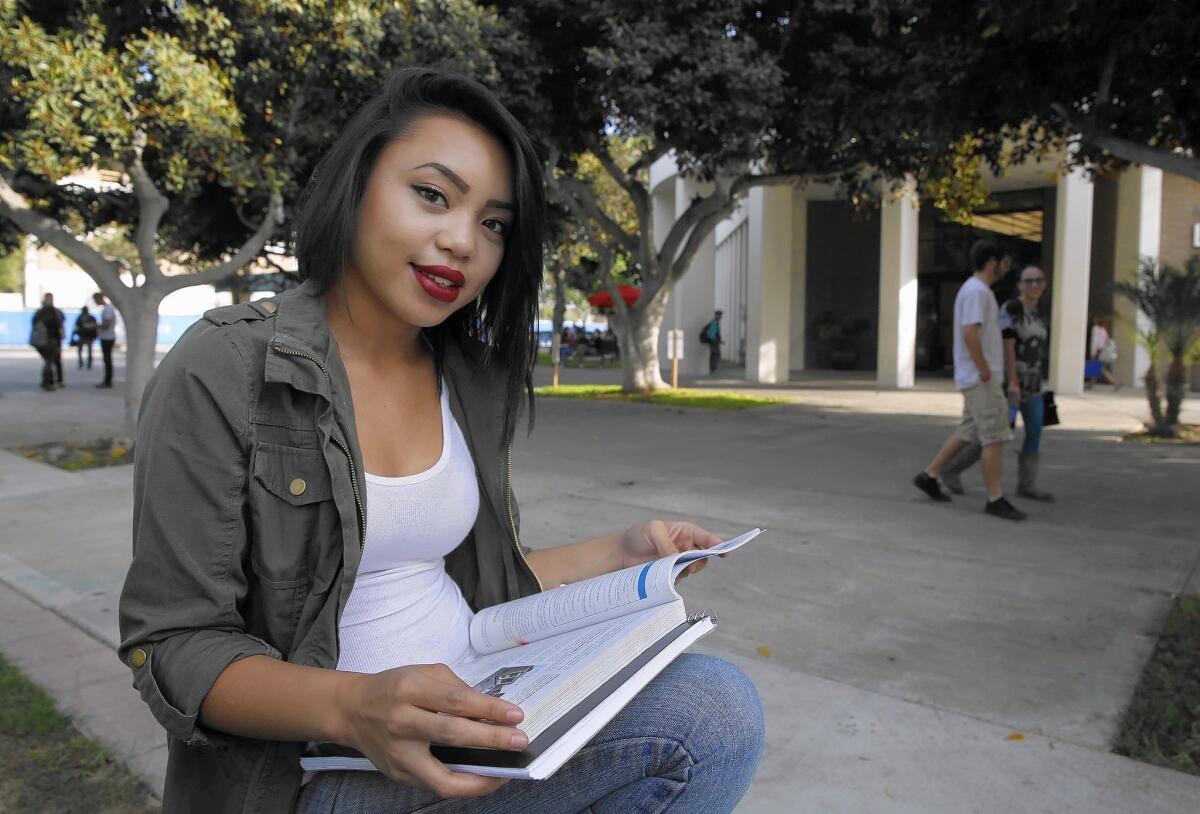

For Katherine Lainez of Oakland, mistakes in her financial aid application at Cal State Dominguez Hills nearly derailed her. At first, she was offered large loans and no grants, making it impossible to attend. But a uAspire counselor helped her appeal with accurate income forms and gain substantial state and federal grants in mid-August. Now the 18-year-old is living in a Dominguez Hills dorm and hoping to major in criminal justice.

Lainez said it would have been unlikely for her to get through the complicated financial aid process on her own in time. “I wouldn’t have been in college or it would have taken me way longer to graduate,” she said.

larry.gordon@latimes.com

Twitter: @larrygordonlat

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.