At renovated Hall of Justice, a bittersweet return for key backer Baca

As photographers jostled for position, Los Angeles County officials posed in front of a plaque that bore their names outside an iconic building.

For years to come, people who enter the Hall of Justice will be reminded of the role those officials played in turning the downtown Los Angeles landmark from an earthquake-damaged husk back into a law enforcement hub.

But standing nearby, without a single camera lens trained on him, was the man who perhaps more than anyone else made the $231-million seismic retrofit and renovation happen.

Instrumental in securing support and funding for the project, former Sheriff Lee Baca also left his mark on the historic edifice. For years, even as problems festered in his department’s jails, Baca obsessed over the tiniest of details, from the bathroom tiles in the women’s restroom to the color of the window trim.

He suddenly retired before his name could be etched on the building — one more piece of fallout from the scandals that broke during his watch. Soon, as sheriff’s and district attorney’s officials move in, someone else will occupy the office Baca so carefully designed for himself.

His appearance at a dedication ceremony for the building last week was a bittersweet moment for the man who had invested so much in the project.

“There isn’t anything about this building that I didn’t have my hand in,” Baca said.

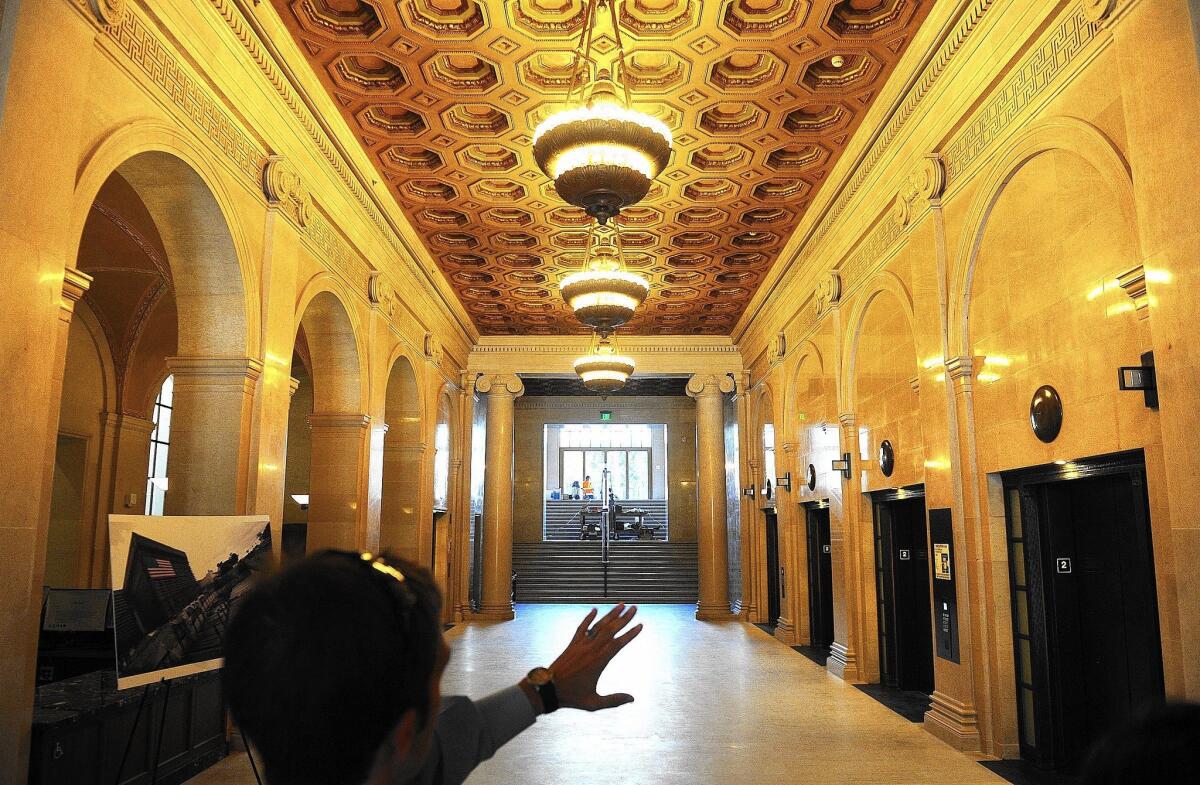

After the ceremony, as crowds surged into the Beaux Arts-style Hall of Justice’s grand lobby, with its gilded arches and ornate ceiling, Baca was no longer alone. Tall and rail-thin in a dark pinstriped suit, accompanied by his wife, Carol, he accepted a hug from just about everyone who passed.

Many Sheriff’s Department veterans told him they were sworn in there, before the Northridge earthquake rendered the building uninhabitable for two decades.

Baca, too, remembers walking up the main steps on Spring Street, cater-corner from City Hall, as a young deputy sheriff reporting for his first day of work in 1965. The building’s 14-story granite facade left him awe-struck at the higher meaning of his new job, he recalled.

In those days, thousands of jail inmates occupied the upper floors. The trials of Charles Manson and Sirhan Sirhan took place in the Hall of Justice’s courtrooms. But as the building, which dates from 1925, continued to accumulate history, it was deteriorating physically.

In 1993, the Sheriff’s Department moved its headquarters to a modern building on a hilltop in Monterey Park. The following year, the earthquake dealt the Hall of Justice what appeared to be a death blow.

While others advocated mothballing it because of the expected cost of renovation, Baca made it one of his pet projects after he was elected sheriff in 1998. More than a decade later, in 2011, the county Board of Supervisors approved a financing plan that relies on savings from canceled leases after about 1,500 employees relocate to the Hall of Justice.

As the project got under way, Baca turned his attention to aesthetics. The window frames would be a putty green to match the trim at City Hall, which was built with granite from the same quarry. The carpet would be beige with darker accents. The parking lot had to blend in with the main structure. An atrium at the building’s center would give employees an outdoor space to have lunch.

“He put a lot of effort into this, and for him not to be there at the end, I think it’s a shame,” said Michael Samsing, an asset planner in the county’s chief executive office. “If it wasn’t for him, this building wouldn’t be where it is.”

While he was putting his personal stamp on the Hall of Justice, Baca was having trouble managing the nation’s largest county jail system. A wide-ranging FBI probe of the jails led to the criminal conviction of seven sheriff’s officials for obstruction of justice and charges against several others accused of assaulting inmates or visitors.

Sheriff’s commander Bob Olmsted, now retired, said that as a supervisor in the jails, he rarely saw Baca.

“Would a CEO of IBM or Apple be so interested and concerned about the color of the carpeting as opposed to what the true mission of the operation is?” said Olmsted, an outspoken critic of Baca’s administration. “If you get lost in the minutiae and minor details, you lose track of big issues, like mental health and jail abuse.”

Baca’s interest in architecture and interior design extended to the three sheriff’s stations built during his tenure. In 2010, he was not pleased with the bathroom tiles or the toilet stall partitions at the new South Los Angeles station. At a cost of more than $22,000, he ripped out the fixtures and installed ones more to his liking.

The Hall of Justice bathrooms are finished in gray tile that Baca picked himself.

Baca said he tried to steer the jails in a different direction but encountered resistance. “I paid a lot of attention to the jails,” he said. “The jails did not pay enough attention to me.”

From an office on the Hall of Justice’s eighth floor, the next sheriff will look northeast across Los Angeles County, with Chinatown and Dodger Stadium in the foreground and the San Gabriel Mountains in the distance.

Previous sheriffs occupied the same corner but on the second floor. Baca said he moved the office to a higher perch to give the sheriff a view of the people he or she serves. “They are working hard in their jobs, they are traveling this incredible network of roads and freeways, and your job is to serve them, not sit in your office and just do administrative work,” Baca said.

Interim Sheriff John Scott, who was sworn in at the Hall of Justice in 1969, will spend his last day, Dec. 1, there as a symbolic gesture, even though the rest of the department will not move in until early next year. It was Scott’s name, not Baca’s, that went on the dedication plaque.

The eighth-floor office’s next occupant will be one of two men facing off in the Nov. 4 sheriff’s election: retired Undersheriff Paul Tanaka, who spent 31 years in the department, or Jim McDonnell, an LAPD veteran who is chief of police in Long Beach.

Standing on the carpet he chose, Baca pointed out the translucent panels in the secretaries’ area, designed to admit light from an adjacent hallway. As he explained his need for multiple secretaries, he lapsed into the present tense.

“I get emails, phone calls, letters — 25 to 30 invitations a day,” he said.

Since his retirement in January, Baca has been working in the garden of his 1928 Mediterranean house in San Marino. At age 72, he runs six to eight miles each morning, has learned how to use a computer and is reading a biography of Mark Twain.

As he left the Hall of Justice behind, he pronounced himself satisfied.

“I wanted it to be airy and light, with natural light coming in, and I think I’ve achieved that,” he said.

cindy.chang@latimes.com

Twitter: @cindychangLA

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.