The [expletives] are flying at Board of Supervisors meetings. We counted them

For decades, the weekly meetings of the Board of Supervisors have been family-friendly, orderly affairs — humdrum public discussions of the appointments, motions and ordinances that keep Los Angeles County’s $30-billion government in motion.

Lately, though, those discussions have turned offensive.

To the exasperation of supervisors, historically called the “five little kings” for their expansive powers, the county’s business is now increasingly interrupted by slurs, epithets and profanity from the public — an issue that’s long been a headache for their colleagues at City Hall and one the supervisors, for all of their power, seem powerless to stop.

According to a Times analysis of a decade of board transcripts, the number of profanities uttered has escalated sharply since the beginning of the year.

A small but bold group of gadflies has discovered that they can routinely disrupt the supervisors’ expectations for decorum in the time allotted for public comment, sending routine discussions about housing policy or mental health resources into a “gauntlet of foulness,” as Supervisor Sheila Kuehl calls it.

“It creates a really toxic environment, not for only us, but for the people in the auditorium,” she said. “It has a chilling effect on other people who come to the board to talk.”

County officials have been unable to muzzle public speakers — even when they use racial slurs and epithets that can inflame tensions in the audience — because of the widespread understanding that comments in public meetings are constitutionally protected. Various attempts have been rejected in federal court over the years.

It’s a common problem in government proceedings across the nation, including for the Los Angeles City Council and even the Los Angeles Police Commission. At those weekly meetings, profanity-laced tirades and middle fingers regularly outnumber the officers assigned to keep watch.

“In one of the largest cities in the world, it is to be expected that some inhabitants will sometimes use language that does not conform to conventions of civility and decorum, including offensive language and swear-words,” wrote U.S. District Judge Dean Pregerson in a 2013 ruling on behalf of local residents who had sued City Hall over attempts to control their rants.

“It is asking much of City Council members, who have given themselves to public service, to tolerate profanities and personal attacks, but that is what is required by the First Amendment.”

That requirement has led to some awkward and tense moments at the Hall of Administration, where the supervisors meet each Tuesday.

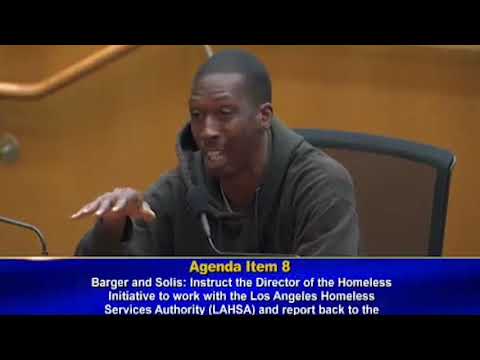

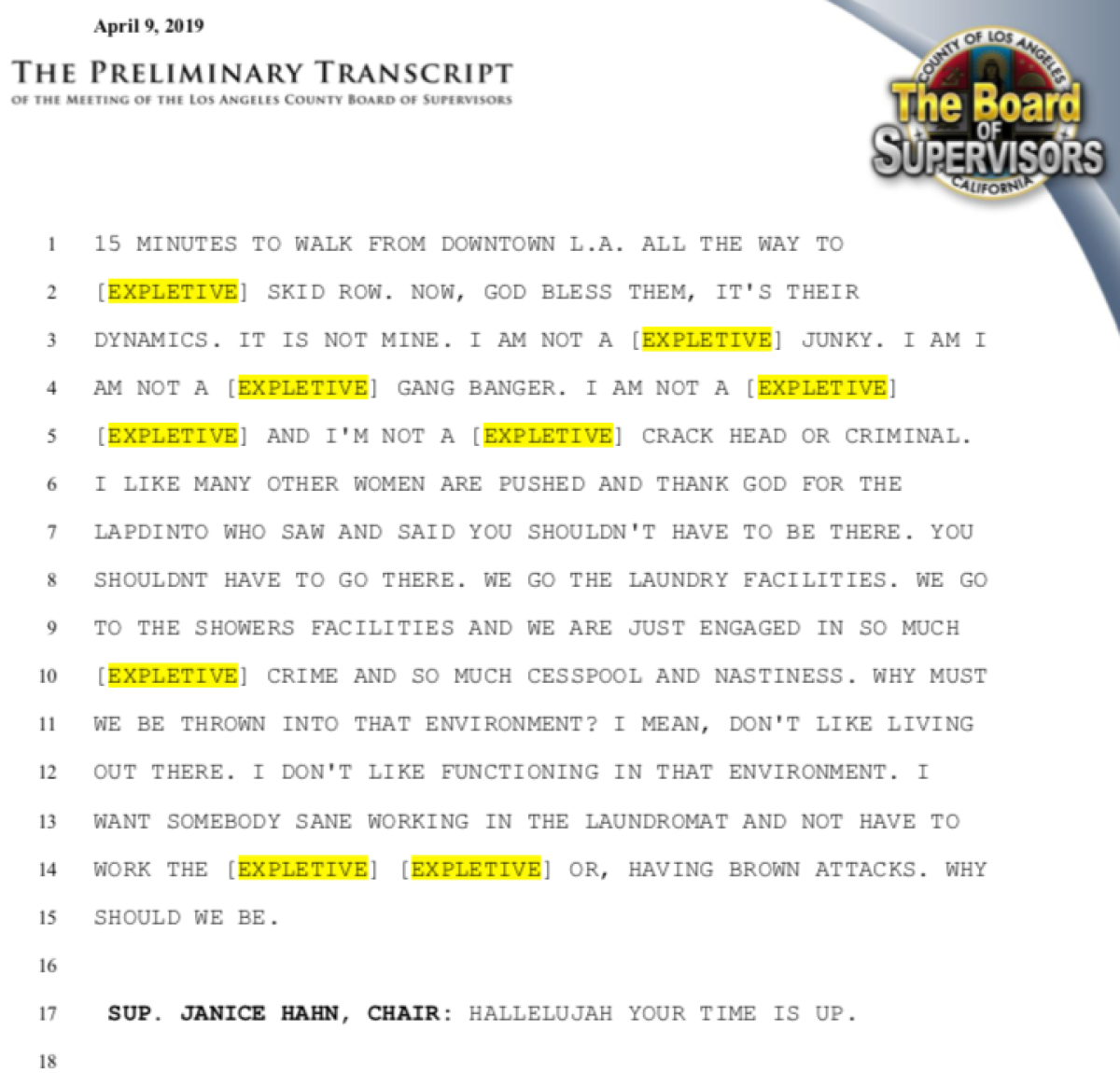

According to a Times analysis of a decade of board transcripts, the number of profanities uttered at Board of Supervisors’ meetings has escalated sharply since the beginning of the year. These clips are from the April 2 meeting.

Members of the public are granted up to three minutes to opine about county business — as actor Brad Pitt did on April 9 to support funding a new building for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

At the same meeting, dozens of housing advocates pushed supervisors to approve an ordinance extending protections for renters through the end of the year.

Amid the mostly civil comments, a meeting regular named Antonia Ramirez used her turn at the microphone to unleash a torrent of profanity aimed at blacks and Latinos watching the meeting, using slurs like “wetbacks” and “chango,” the Spanish word for monkey.

“Deport them. Public safety must be restored. Shut the border and build the wall,” Ramirez continued. “Again, we want our beloved America back.”

Some in the audience stood, surprised by the outburst. Others booed.

“It’s obviously hurtful to see people who have these beliefs. It’s offensive to hear them,” said one attendee, Chris Estrada, director of community organizing with the tenants’ rights group, L.A. Center for Community Law In Action.

Estrada said he spends his time trying to get his clients to feel safe challenging the system. These types of comments in meetings don’t help.

“That adds more of a challenge to reassuring them and encouraging them to fight,” he said.

Supervisor Janice Hahn, who chairs the board and sometimes interacts with public speakers who use offensive language, later pleaded with Ramirez to steer clear of such talk.

“Now, you have the freedom of speech and you’re allowed to say what you want. But I will say your language is very offensive to a lot of people today,” Hahn said. “I’m just asking you. I can’t force you. But I’m asking you to work on your language.”

Ramirez was defiant.

“I make no apologies for my verbiage,” she replied. “And if they get offended, ask them why.”

Days later, Ramirez went to a City Council meeting and complained about “Masonic Jewish Zionists,” used the N-word and said “kill Eric Garcetti,” referring to L.A.’s mayor — all during a one-minute rant.

Earlier in April, Hahn sparred with another frequent speaker who often uses profanity, Armando Herman, who regularly exasperates the supervisors.

“What the hell is going on?” Hahn said in an exasperated tone, as the speaker dropped three F-bombs in one sentence.

By the end of the public comment period, Hahn exhaled with a “Lord, have mercy.”

The situation improved slightly this week, with speakers spewing fewer expletives. Still, Hahn jousted with Wayne Spindler, a lawyer and frequent speaker who was arrested in 2016 after a particularly caustic appearance at City Hall. He has also sued in federal court over his right to free speech, with mixed results.

The Times analyzed more than 400 transcripts of weekly meetings between January 2010 and April 2019, counting uses of the word “expletive” — a catch-all redaction used by those who transcribe the meetings in real time for television closed captioning.

The word appeared only occasionally until recent years. In 2013, for example, more than 1.8 million words were uttered during supervisors meetings. Three were redacted with the word “expletive.”

But since last fall, “expletive” has appeared hundreds of times, spiking in the first two weeks of this month, when nearly 70 profanities and slurs were used. So far this year, offensive words have been used more than 170 times.

It’s unclear to observers what’s driving the trend, which also is evident in recent City Hall transcripts, where foul language aimed at black, Latino and LGBTQ communities has been a sore spot for years.

“That is the part of the price we pay for this experiment of freedom of expression,” said Stephen Rohde, a retired civil rights lawyer who represented the plaintiff, Matthew Dowd, in the case involving L.A. City Hall. “It is literally one of the prices we pay for a robust democracy.”

Kuehl, who also is a lawyer, said she appreciates the right to freedom of expression, but not what she calls “assaultive” outbursts. She worries it will deter the public from experiencing the business of their government.

When a public speaker uses certain words or slurs, Kuehl said people in the audience look stunned.

“They do expect that we will do something to protect them from this kind of verbal assault,” she said. “And the fact that we don’t makes them feel unsafe.”

Times staff writers Mark Puente and David Zahniser contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.