Jahi McMath: Time is limited for brain-dead teen, experts say

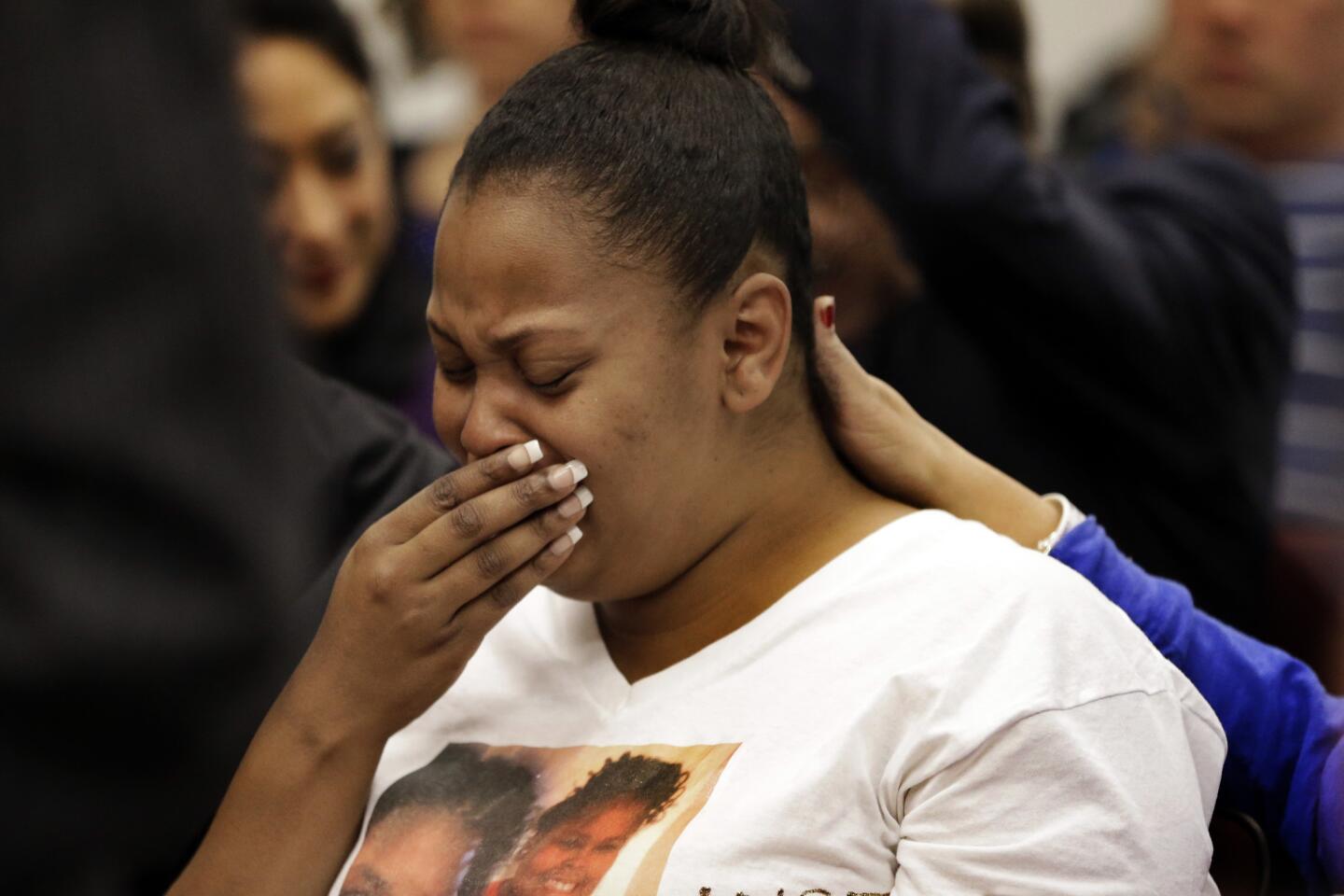

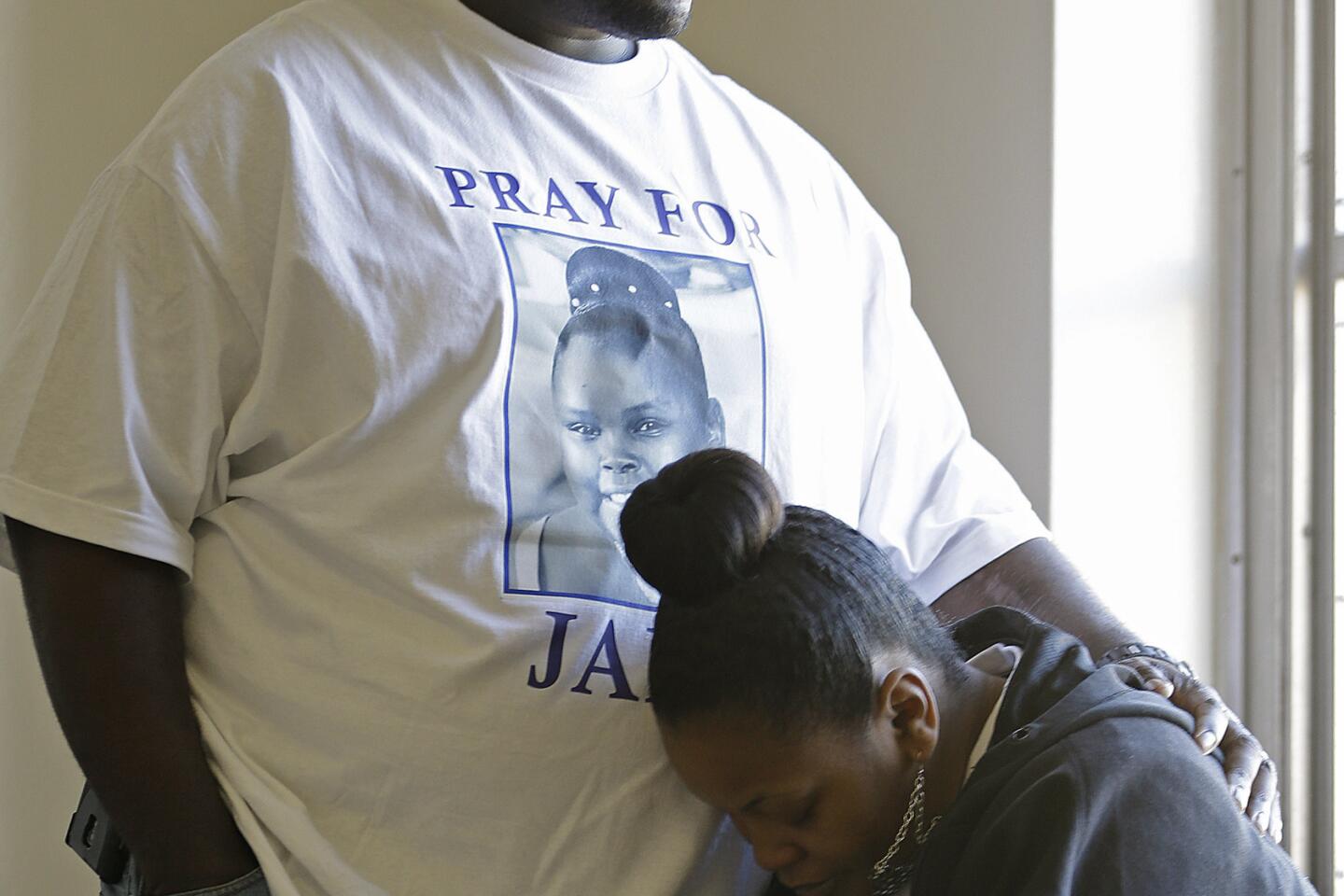

The family of 13-year-old Jahi McMath may have succeeded in transferring the brain-dead teen from an Oakland hospital to undisclosed care facility, but medical experts say it’s only a matter of time before not even machines can keep her blood flowing.

Bodies of the brain-dead have been maintained on respirators for months or in rare cases even years — and in a few other cases released to families.

But once cessation of all brain activity is confirmed, there is no recovery, said Rebecca S. Dresser, professor of law and ethics in medicine at Washington University in St. Louis, who served on a presidential bioethics council that in 2008 reaffirmed “whole-brain death” as legal death.

Brain cells die without blood flow and autopsies in such cases have shown that the brain liquefies.

After marathon negotiations with a federal magistrate, Jahi’s family members received approval to remove her body, while attached to a ventilator, from Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland on Sunday.

The brain-dead girl was released first to the Alameda County coroner and then to the family, and is now the responsibility of her mother, who has moved her to an unnamed facility.

The courts have so far agreed that Jahi is dead. The coroner on Friday issued a death certificate listing Dec. 12 as the date of death.

But bioethics experts say news media coverage that often repeated family assertions that Jahi McMath was alive — even responding to touch — clouded an issue the public already has difficulty grasping.

The Oakland girl underwent surgery Dec. 9 to remove her tonsils, adenoids and uvula. She was declared brain-dead after she went into cardiac arrest and suffered extensive brain hemorrhaging.

At least three neurologists confirmed that Jahi was unable to breathe on her own, had no blood flow to her brain and had no sign of electrical activity.

What followed was a court’s order — extended once — that the hospital keep the ventilator on, first while an independent neurologist confirmed Jahi was brain-dead, then as the family scrambled to find a facility that would accept a patient declared deceased.

All the while, the breathing machine kept Jahi’s lungs and heart working.

Jahi’s family — and their attorney, Christopher Dolan of San Francisco — have maintained that brain death is not death, that the girl might get better, and that the rights of Jahi’s mother, Latasha Winkfield, to determine the medical course of action were violated.

But California law says the family had no right to make decisions about the ventilator, only a right to a “reasonably brief period of accommodation” after the declaration of brain death to “gather family or next of kin at the patient’s bedside.”

To experts, the case has raised no novel legal issues, but it has created a painful spectacle.

Arthur Caplan, director of the division of medical ethics at New York University Langone Medical Center, said the Jahi case could compel other families to “ultimately say, ‘I’d like to take this body home and wait for a miracle.’ That would be a public policy of disrespect for dead bodies.”

“The ability to get clear about brain death has been a real obstacle,” he said. “This hasn’t helped at all.”

Twitter: @LeeRomney

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.