In Santa Barbara County, oil firms and environmentalists square off

Seen from U.S. 101, northern Santa Barbara County looks to be mostly vineyards and cattle ranches, with majestic oak trees scattered across the dry rolling hills.

But up a narrow road, spread across the chaparral between Orcutt and Los Alamos, wells drilled deep into the shale have yielded more than 180 million barrels of oil in the 113 years since Union Oil Co. geologist William Orcutt first surveyed the area that would soon bear his name.

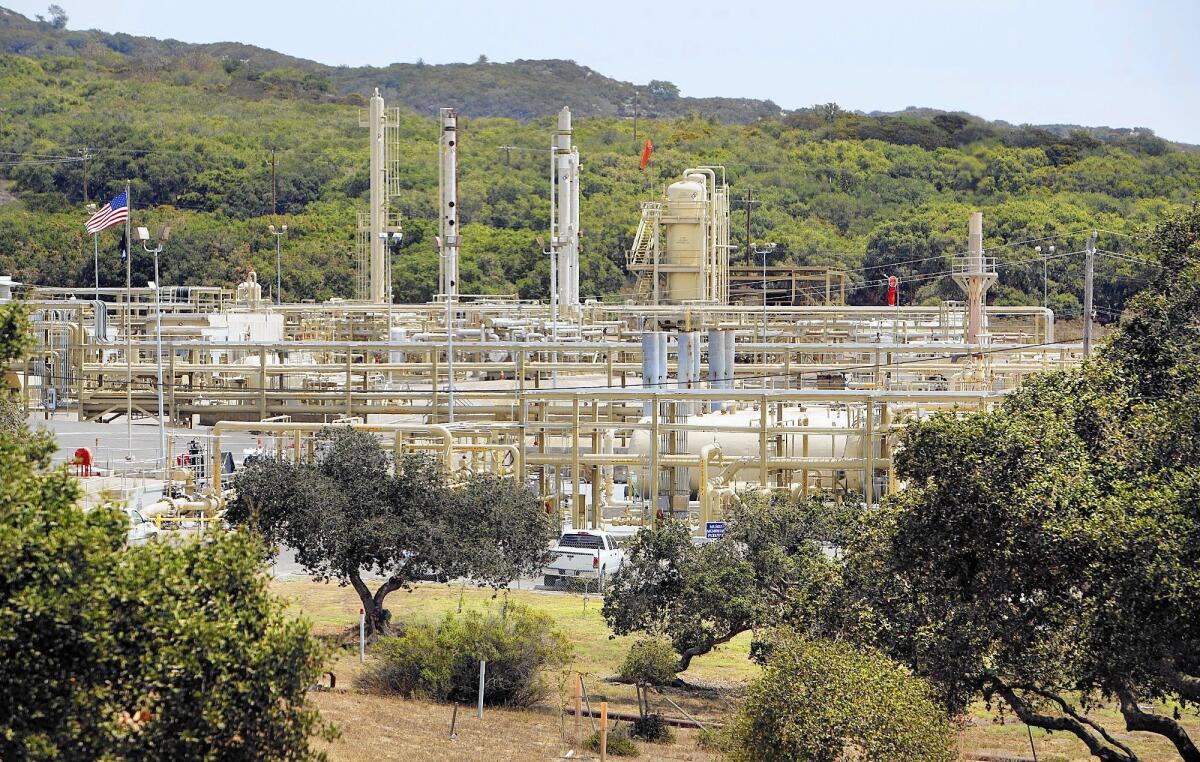

The bobbing pump jacks, pipelines and tanks on Orcutt Hill, not visible from the highway, now produce 3,500 barrels of oil a day for Pacific Coast Energy Co. But company managers say the 6,000-acre operation, like similar ones nearby, is threatened by a November ballot measure that would ban “high-intensity petroleum operations” in the county.

“It will, in fact, shut down onshore oil production in Santa Barbara County,” said Dick Hart, who oversees Orcutt Hill for Pacific Coast Energy. “Thousands of people are going to lose their jobs.”

Supporters of Measure P say it would have no effect on conventional oil drilling and leave all existing operations intact. What it would ban, they say, are aggressive oil and gas extraction methods that can trigger earthquakes, contribute to global warming, pollute aquifers and, at a time of severe drought, waste rapidly depleting groundwater supplies.

“We can’t afford to let these companies use our water,” said Rebecca Claassen, co-founder of Santa Barbara County Water Guardians, the group that petitioned to put the measure on the ballot.

Energy companies have fought similar measures around the country. But Santa Barbara’s long history of tension between oil companies and their critics gives the Measure P campaign a symbolic weight that has not been lost on energy executives.

In 1969, the county’s scenic coastline was befouled by an oil spill that served as a catalyst for the modern environmental movement and spawned some of the nation’s core anti-pollution laws.

Chevron Corp. and other energy companies have hired a team of California’s top political consultants to fight the measure. It would constrain land-based drilling, mainly in the hills around Lompoc, Orcutt and Santa Maria, but have no effect on platforms offshore.

The campaign has barely begun, but the two sides already are trading accusations as each tries to frame public debate on a proposal with technical aspects that can be easily misunderstood.

The most controversial procedure the measure would ban is fracking, or hydraulic fracturing — the cracking of deep underground rock formations and injection of chemical fluids to ease the extraction of oil or gas. Communities across the nation, including Los Angeles, are weighing fracking bans.

Fracking has occurred in recent years in the hills between La Cienega Boulevard and West Los Angeles College, in the Santa Susana Mountains near Porter Ranch, in the mountains around Ventura and Fillmore, and under the seafloor off Ventura.

Venoco Inc. has acknowledged fracking in late 2009 and early 2010 in the winemaking area between Los Olivos and Vandenberg Air Force Base. A rancher’s chance discovery that it was taking place under his vineyards led Santa Barbara County to start requiring permits for fracking. Oil companies say the county’s shale is poorly suited to fracking, and none has taken place there in the last four years.

But the industry has stepped up its use of steam injection in Santa Barbara County — a process Measure P would also prohibit. It involves heating water to produce steam, then shooting it into rock a mile or two deep to loosen heavy crude deposits. The Orcutt Hill site includes 100 steam wells, and Pacific Coast Energy has applied to drill 96 more.

Alarmed by efforts in Santa Barbara, San Benito and Butte counties to ban fracking, steam injection and other drilling methods, petroleum trade groups formed a campaign committee, Californians for Energy Independence. Its initial source of money — $464,483 — was Freeport-McMoRan Oil & Gas, which is planning a steam project near Lompoc. Other companies — Pacific Coast Energy and a related business, Breitburn Energy, among them — recently donated nearly $1.4 million more. Chevron’s $1.2-million donation was the biggest.

Nearly a third of Santa Barbara County’s 1,167 active onshore wells already use steam injection, and the ballot measure would exempt those from the ban, according to the county.

To produce steam, some operators heat recycled wastewater. But others use fresh water, so Measure P’s supporters argue that oil companies are squandering scarce groundwater.

Environmentalists also say the danger of groundwater contamination was underscored last month when the state shut down 11 wells in Kern County that were used to dispose of drilling wastewater. State inspectors are checking whether toxics leaked into the underground drinking water supply. They believe acid well stimulation — which the Santa Barbara measure would also ban — was used to drill some of the oil.

“We can’t afford to keep doing this in this state until we’re absolutely sure that it isn’t creating havoc for public health and the environment,” said Kathryn Phillips, director of Sierra Club California. “The last thing you want is water that is unpotable and could never be cleaned up.”

Energy companies say those fears are unfounded. Aquifers, they say, are relatively shallow, and wells that pass through them to reach deeper oil and gas deposits are sealed in concrete.

“This is a red herring,” said Bob Poole, government and public affairs manager at Santa Maria Energy, a company expanding its steam drilling at the Orcutt oil field. “It’s a false argument.”

Critics of steam injection also cite the greenhouse gas emissions that come from burning gas to heat water. But California’s cap-and-trade program to fight global warming, Poole said, requires Santa Maria Energy and other oil companies to offset increased emissions by paying for greenhouse gas reductions elsewhere.

Oil production in Santa Barbara County dates to 1886, when drilling started in Summerland. The industry has faced periodic resistance ever since, including a 1929 protest against drilling within the city of Santa Barbara, by then a popular beach getaway for the well-to-do.

The industry’s biggest setback came with the uncontrolled 1969 blowout on Union Oil’s Platform A, six miles off Santa Barbara. It remains the largest oil spill in California waters. It blackened beaches from Ventura to Goleta, filled Santa Barbara harbor with thick crude and killed birds, dolphins and other sea life.

County officials have been cautious in estimating Measure P’s potential effect. If it passes, they say, an immediate drop in tax collections is unlikely, but a gradual decline over 20 years would occur. In 2013, oil companies paid $16 million in local property taxes, 3% of the total.

In the campaign ahead, a key focus will be whether the measure’s wording might require the county to deny new permits even for conventional drilling, as oil companies contend.

“The way it’s written, I would say there’s some ambiguity,” said Kevin Drude, deputy director of the county’s Energy Division.

The measure’s supporters say the county Board of Supervisors can pass legislation affirming that conventional drilling is not covered by the ban on “high-intensity” operations. The industry, they say, is overstating the measure’s effect as a scare tactic.

In the fall campaign, energy companies are widely expected to outspend Measure P’s supporters. Both sides agree the proposal’s most receptive audience is in the prosperous coastal areas around Santa Barbara and Montecito, while strong opposition is likely in more rural, Republican and blue-collar areas around the onshore oil fields.

“People have pretty strong feelings about oil here,” said Linda Krop, chief counsel of the Environmental Defense Center in Santa Barbara, “and it hasn’t really changed.”

Twitter: @finneganLAT

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.