FBI unable to break into Texas church gunman’s cellphone

The FBI has been unable to access the phone of the Texas church gunman, officials said Tuesday, voicing their frustration with the tech industry as they try to gather evidence about Devin Kelley’s motive for killing 26 churchgoers in a small town outside San Antonio.

“With the advance of the technology and the phones and the encryptions, law enforcement — whether that’s at the state, local or federal level — is increasingly not able to get into these phones,” Christopher Combs, the special agent in charge of the FBI’s San Antonio bureau, said in a televised news conference.

Combs declined to say what type of phone Kelley had, “because I don’t want to tell every bad guy out there what phone to buy.”

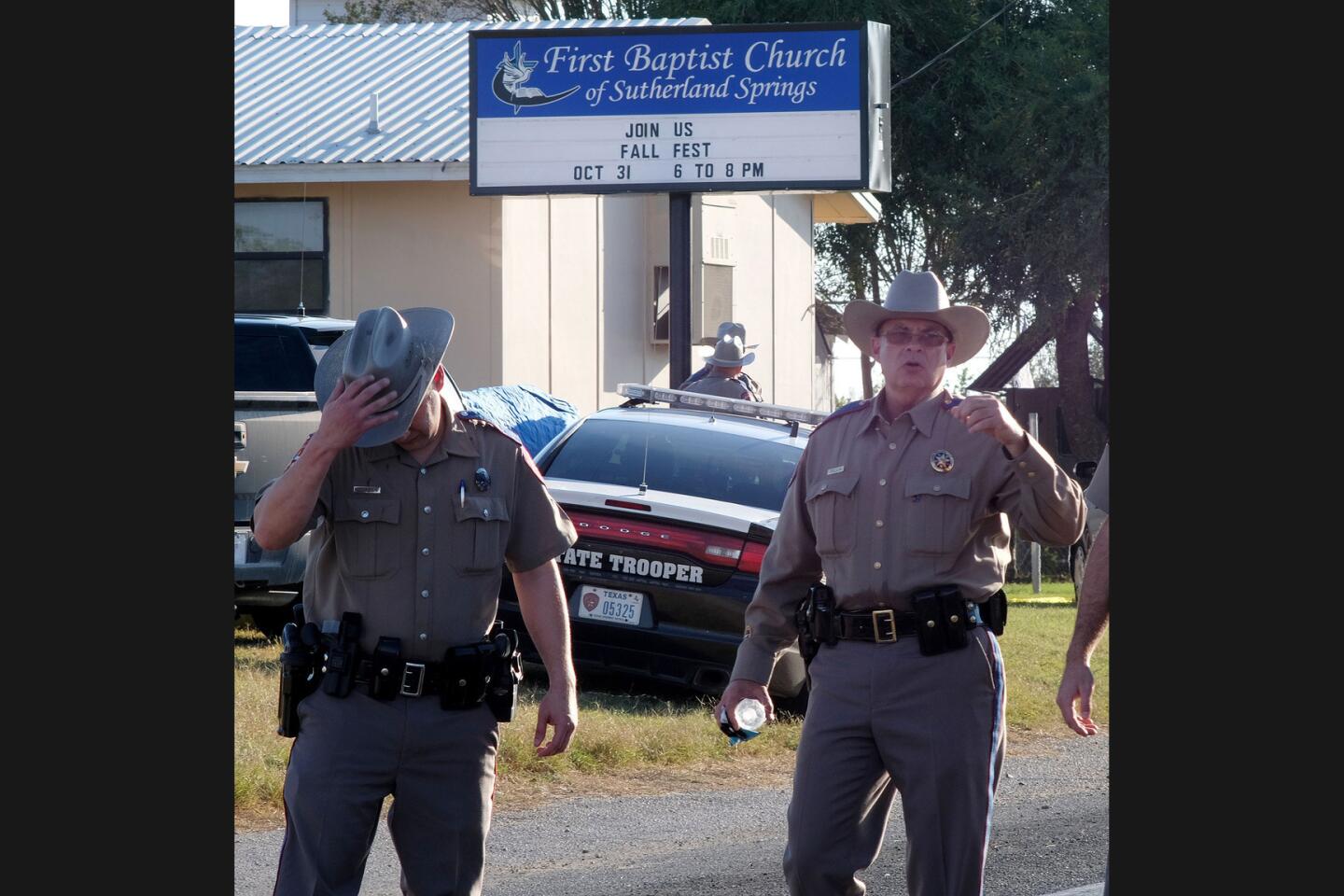

The revelation came as investigators continued to scour the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, where Kelley fired hundreds of rounds and left behind 15 empty 30-round ammunition magazines after his attack Sunday.

The FBI’s refusal to identify the manufacturer of the phone stands in contrast to its public feud with Apple in the aftermath of the San Bernardino shooting in 2015 that left 14 people dead.

In that case, investigators wanted access to gunman Syed Farook’s iPhone 5C, hoping the device would provide information about possible accomplices or terror networks.

Apple defied a court order to help crack the phone’s pass code, arguing it would set a precedent that would compromise the security of billions of customers.

The FBI eventually paid a private firm $1 million to circumvent Apple, gaining access to Farook’s phone and dropping its lawsuit against the tech giant.

The tension between law enforcement and the tech industry over encryption remains as high as ever.

FBI Director Christopher Wray said last month that federal agents were still seeking access to 6,900 mobile devices.

“To put it mildly, this is a huge, huge problem,” Wray said. “It impacts investigations across the board -- narcotics, human trafficking, counter-terrorism, counterintelligence, gangs, organized crime, child exploitation.”

Earlier in the month, Deputy Atty. Gen. Rod Rosenstein called on tech companies to build “responsible encryption” that would allow access only with judicial authorization.

Tech companies are wary of such requests. The government, particularly the National Security Agency, has proven to be vulnerable to hacking. And if U.S. law ultimately compels companies to provide so-called backdoors to their devices, fears abound that undemocratic countries such as China will do the same.

“Even if you solve the trust problem with the government, you then have a problem with where to draw the line” with other countries, said Robert Cattanach, a former Justice Department attorney who specializes in cybersecurity for the law firm of Dorsey & Whitney.

Cattanach said it was likely the FBI did not name the maker of Kelley’s phone because it appeared unlikely that Kelley had accomplices. There was a greater sense of urgency with Farook because of concerns he might be acting on behalf of a terrorist group.

“You can’t go to a judge and argue there’s a future threat like in San Bernardino,” he said. “So what are you going to do? Public shaming didn’t work with Apple.”

Matt Pearce is a national reporter for The Times. Follow him on Twitter at @mattdpearce.

UPDATES:

1:55 p.m.: This story was updated with background and analysis on the FBI’s past attempts to access data from cellphones of crime suspects.

This story was originally published at 10:55 a.m.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.