From the archives:: Catholicism losing ground in Ireland

MAYNOOTH, Ireland — The black-and-white class portraits arrayed along the nearly deserted corridor of the seminary at St. Patrick’s College here tell the tale.

Year by year, the group of graduating seminary students gets smaller. Slowly, the number of young men willing to replenish the priesthood of the once-mighty Roman Catholic Church in Ireland is shrinking. In the future, the priests celebrating Mass in the Emerald Isle’s churches may well be from South America or Africa, not Cork or Kerry.

Overwhelmed by a tide of secularism and economic prosperity, challenged by a new mood of independence in the population and devastated by a decade of scandals involving serial child abuse by clerics, the Catholic Church in Ireland finds itself demoralized, almost in shock. “Irish Catholicism as we knew it in Ireland is gone,” said Patsy McGarry, religious affairs writer for the Irish Times.The days when nearly everyone was a churchgoing Catholic, the parish priest was revered and church doctrine was central in public policy and private life are no more.

“Ireland has become part of the Western European scene. We have been moving in a secularizing direction. But the pace of all this has been accelerated by the extraordinary leap forward in our country’s prosperity,” Cardinal Desmond Connell, retired archbishop of Dublin, said in an interview with The Times in Rome this month.

“There’s a lot of surplus cash around, and people are enjoying it. I have no trouble with that, but when they enjoy the immediate, they forget the ultimate.”

For Pope John Paul II, who helped to bring freedom of worship to people in Eastern Europe, the erosion of faith and the rise of secularism in the rest of Europe was one of the recurring themes of his pontificate and a trend that only accelerated during his tenure.

But it is doubtful that even John Paul expected the church to retreat as quickly as it did in Ireland, long a bastion of Catholicism and among the first places he wanted to visit after being named pontiff.

On his trip in September 1979, drawing the largest crowds in Irish history and speaking to more than 1 million people in Dublin’s Phoenix Park, he reminded the Irish people of their long loyalty to Catholicism in the face of persecution. He asked them to remain true to that faith, and cautioned against embracing new freedoms or novel ideas about personal morality, which he said led to a new form of enslavement.

Although the pontiff was rapturously received on that visit, which is still fondly remembered, it coincided with the beginning of a long decline. Mass attendance fell throughout the 1980s, a slide that accelerated in the 1990s when the country’s sexual abuse scandals exploded.

In the 1970s, more than 90% of Irish Catholics said they went to Mass once a week. Now the number is 44%, according to a recent survey. (Although a dramatic drop, the level remains high among Western countries.)

In addition, “a la carte” Catholicism took hold and affected political life. Young Catholics began to excuse themselves from certain church teachings, such as the ban on premarital sex. Married couples practiced birth control. The sale of condoms was legalized in 1979, despite church opposition.

In 1995, a referendum amended the constitution to give couples the right to divorce.

A similar measure in 1986 had been roundly defeated.

Despite the setbacks, clerics and other church officials argue that Catholicism is still important to the Irish. People still go to Mass on holy days and for baptisms, weddings and funerals. Most parents still rear their children as Catholics.

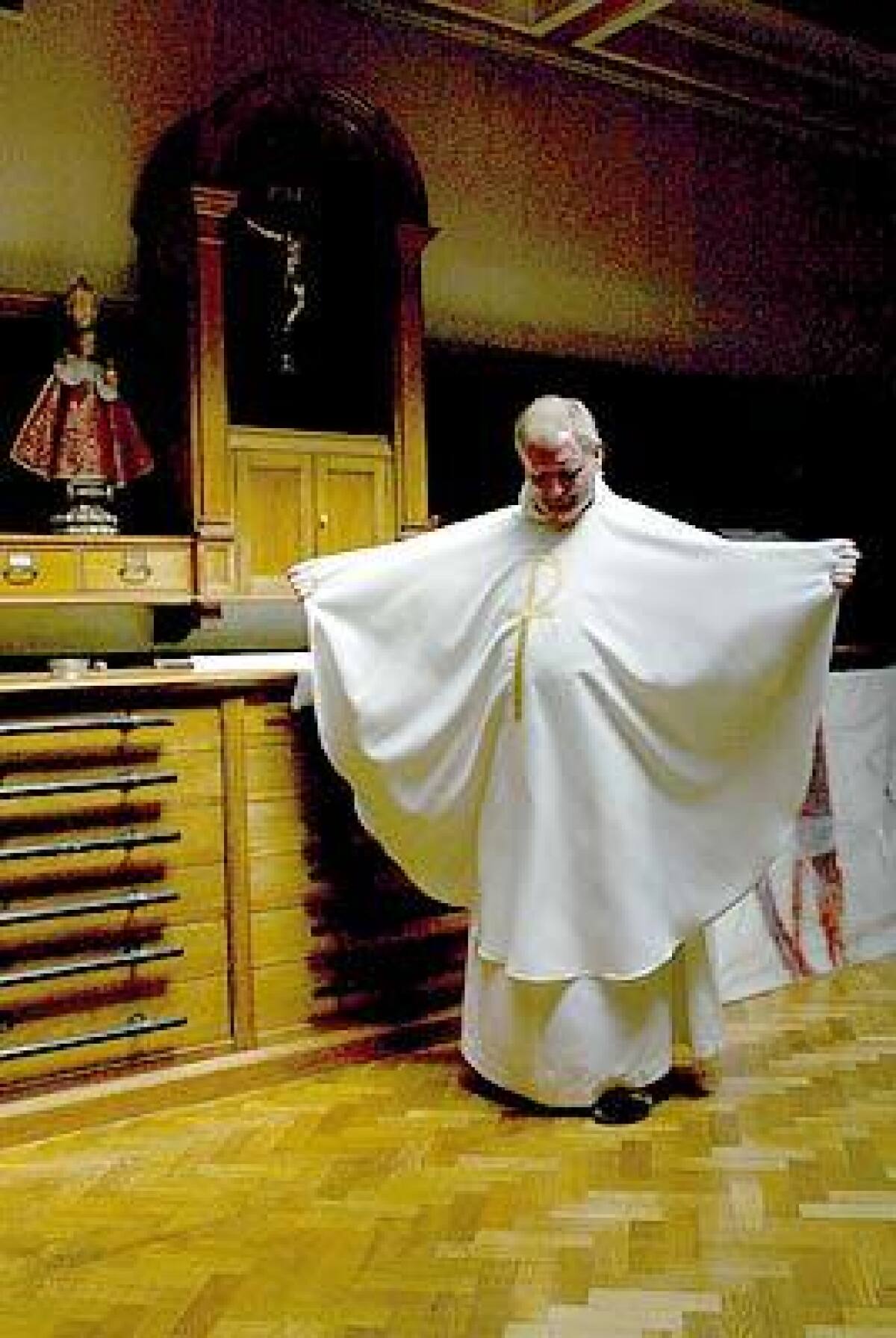

Father James Noonan, 43, prior of St. Teresa of Avila Church, just off trendy Grafton Street in central Dublin, says his church draws large crowds on Sundays. Even on weekdays, dozens of people, young and old, could be seen wandering in from shopping or before or after work to attend Mass, prayers or penance services.

“When priests are available and willing to sit and listen, people will come,” said Noonan, who has a community of nine Carmelite-order priests in residence. The funeral of the pope in particular touched many people in Ireland, he said.

“A lot of people out there felt it very deeply,” Noonan said. “The Christianity is there, but it needs something to tap into that. People are in search of something deeper, and the church is always challenged to respond to that.”

Young people on the streets of Dublin tended to agree. Although most acknowledged that they didn’t attend Mass regularly, most attributed it to being too busy with their studies, or their parents being occupied with shopping or other activities on Sundays. The church, too, was not as strict and did not exert the pressure it used to, some said.

Alan Tobin, 19, a biomedical student at the Dublin Institute of Technology, disagreed that the country had become less religious. “Many people still pray every day,” he said. “It’s just that there is more free will now, and it looks less religious from the outside.”

Perhaps the real challenge for the church in Ireland is whether there will be a next generation of priests.

Ireland produced more priests than it could use for generations, seeding the Catholic Church in other countries. The national diocesan seminary at Maynooth, 20 miles west of Dublin, has turned out more than 11,000 priests since its founding in 1795. They have been sent around the world, including to the United States, and founded major missionary societies in Africa and China.

The campus shows no signs of decline. Planted with ancient trees, flowers and expansive lawns, dominated by the soaring spire and the exquisite stained glass of its chapel, one of the largest Gothic choral chapels in the world, the college and seminary still exude permanence and serenity.

But instead of the 500 or so seminarians who would have studied here in the past, now there are but 60. And the college’s numbers have been bulked up mainly by lay students of both sexes studying theology.

Last year, 15 men were ordained as Catholic priests for the entire island, with 5.6 million people (4.2 million of them Catholic). In the Anglican-linked Church of Ireland, a fraction of the Catholic Church’s size, 19 were ordained, including several women.

John Coughlan, of Sligo, in northwest Ireland, is acutely aware of how much his country has changed. But the stocky 24-year-old with a baritone voice and an easy manner has pledged himself to the church anyway.

As a fourth-year seminarian, due to become a diocesan priest in three more years, he expects his career to be far different from those of earlier generations. Years ago, he says, who could have imagined that a seminarian like him would have his own car parked out in back?

Although few in his generation have chosen his path, Coughlan believes his faith isn’t an anomaly.

“The very fact of my being here means that I am not out of step with my generation,” he said. “Because there is something still there.”

Coughlan said the Irish Catholic Church would have to change in a new environment that included far fewer priests.

“What we see in Ireland is a church that had been more institutional than a community,” he said. “Now the church is searching for community.”

“Mass is important, and so is our meeting after Mass for coffee and doughnuts. When that doesn’t happen, people are missing out,” he said.

He does not expect to lead and rule over a parish. Instead, he will be part of a team in which lay people have prominent roles. And if people choose not to come to church, then he must take the initiative.

“That means I go out there as a priest five or 10 years from now and I do what the Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Mormons do. I knock on people’s doors, and I say, ‘I am a priest and I just wanted to meet you and maybe let’s have a chat and a cup of coffee,’ and that’s where it starts. That’s where it’s at,” Coughlan said.

In fact, some conservative Catholics suggest a different kind of church may emerge in Europe because of its current crisis. The Catholic Church they foresee would be smaller, unbending in its teachings, and relying more on lay people to reawaken Christian passions for those who want to follow.

“The liberals [in society] have had the pitch for 20 years,” said Simon Rowe, 32, a founder of a new independent Catholic newspaper here, called the Voice, which has hired a staff of 15 and puts its focus on culture, faith and family.

A conservative Catholic who clearly hoped to set a spark, Rowe said that the church should offer young people an alternative to Europe’s dominant liberal secularism.

He said there was a chance for the church to propose “a vibrant orthodoxy” to replace a “jaded liberalism.”

“I think to be a Catholic today is the real liberalism, the real radicalism,” he said.

He cited John Paul’s teachings to the young, which he said could apply to the next generation of Catholics in Ireland.

“He said be what you are, and you will set the world ablaze…. Rather than conform to the world, the world will conform to you.”

Times staff writer Richard Boudreaux in Rome contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.