Mexico poet an emblem of nation’s drug war carnage

He is now a poet absent words, a father without a son — a 54-year-old man, Javier Sicilia says, who inhabits a “broken life.”

The award-winning writer has also become an anguished emblem for Mexicans horrified by the continuing drug-related carnage sweeping their nation.

In March, Sicilia’s 24-year-old son, Juan Francisco, was seized by gunmen in the city of Cuernavaca, then strangled and his body dumped along with six others. Police say orders came from a notorious cartel henchman, though they have said Sicilia’s son, a business student, had no ties to crime.

To the left-leaning Catholic poet, novelist and essayist, the pointless slaying is yet another sign of the government’s failure to safeguard its people in the midst of what he considers an ill-conceived war against drug gangs.

“The horror we are experiencing each day took him away,” Sicilia said during an hourlong interview in which he steered between sadness and disgust, puffing a steady string of Delicados cigarettes.

Sicilia — gentle-spoken yet opinionated — was traveling in the Philippines when he learned of the tragedy. He scribbled a poem to Juan Francisco on a piece of scrap paper and returned to Mexico, vowing he would never write his spiritually tinged poetry again. Words, he says, are unworthy of sacred expression.

Instead, Sicilia has turned his indignation and relative fame toward President Felipe Calderon’s war on drug cartels, which he blames for igniting the orgy of killing that has left more than 38,000 people dead since 2006. Sicilia said the violence has turned the country into a no-man’s land.

“It’s a war in which the ones who are caught in the middle are the people,” he said.

Sicilia has been questioned for having aimed his criticism mainly at the Calderon government even though drug hit men are suspected of killing his son and so many others. The writer counters that it is Mexican authorities, not criminal cartels, who are responsible for keeping the public safe. Asking ordinary Mexicans to plead with the drug gangs, he said, is tantamount to admitting a vacuum of official authority.

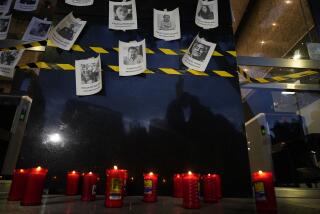

Dressed in a felt Stetson hat and miner’s boots, Sicilia led a 60-mile march from Cuernavaca to Mexico City’s main plaza for a demonstration that drew tens of thousands of people this month. Participants waved placards that urged an end to the violence, declaring, “We’ve had it up to here!”

The protest followed several smaller gatherings and marked the largest grass-roots repudiation of the Calderon administration’s military-led drug war. In remarks that day, Sicilia called for the resignation of the country’s public safety secretary, Genaro Garcia Luna, and assailed political parties across the board.

The pressure has forced Calderon to step up efforts to sell his anti-crime strategy to a public that appears increasingly wary as the toll continues to rise. Calderon, a conservative, says his government is making headway and should keep up the campaign.

Sicilia asserts that the slaying of his son, and the indignation he has personified during weeks of public comments, represents a “breaking point” in the drug war by turning unease into public action. In the short run, he said, the most that might be gained is a change in the terms of the crackdown.

“It puts a name on the grief and serves as an X-ray of a heedless state, and criminality that is able to do what it does because of the cooptation of the state, the rottenness, the impunity,” Sicilia said.

It is almost surely premature to talk of turning points in a drug war that has seen massacres, decapitations, assassinations and a steady parade of bereaved, sunken-eyed parents.

It’s also not clear whether the budding movement can last. Mexicans have taken to the streets before to decry other episodes of violence, only to see it worsen as official promises faded. And Mexico’s political system has long tamed critics by inviting them inside.

For the moment, attention is on six broad demands that Sicilia and close associates crafted for the march, which began May 5 and ended in the capital three days later. The list urges an end to the “war strategy” and calls for attacking corruption and the “economic roots” of crime, meaning poverty and joblessness. Organizers also demand that authorities solve crimes and repair Mexico’s social fabric.

Sicilia and fellow organizers see the demands as a basis for pushing Mexico toward sweeping change. Civic groups are to meet next month in violence-ravaged Ciudad Juarez to endorse the document. Sicilia and associates also plan to meet with Calderon.

Though short on specifics, Sicilia said the movement is looking beyond the issue of violence by advocating an overhaul of Mexico’s graft-laden political system across party lines. Their goal, he said, is a nation where residents trust police enough to report crimes, wrongdoers are punished and politicians pay heed to constituents.

“It’s a re-foundation of the state,” Sicilia said. “A peaceful revolution.”

He also has a message for Americans who use illicit drugs: Blood is on your hands too.

Sicilia, who counts the ideas of social critic Ivan Illich, mystic Lanza del Vasto and nonviolence icon Mohandas Gandhi among his inspirations, has long offered his opinions in left-leaning publications such as Proceso and La Jornada and in his own journal, Conspiratio.

But he seems uncomfortable as figurehead for a protest movement and has stumbled at times, such as when he appeared to suggest that authorities should make deals with drug bosses as a way to ease violence. (Sicilia says he did not mean that.)

Some critics say his call for Garcia Luna’s removal was also misguided.

“What he says might be mistaken at times or be a political error … but it will be absolutely sincere and from the soul,” said Jose Antonio Crespo, a political analyst who has known Sicilia more than 30 years. “He will say what he thinks.”

Sicilia, who is divorced, said he will continue serving as moral leader of what he calls “a communion of grief.” But he is eager to retreat to the familiarity of the writer’s life, even one without poetry. He plans to continue writing political commentary and other prose.

“To be involved in a controversial political process is difficult, especially with the pain I carry, with my broken life,” he said. “I am not a politician. I’m a poet.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.