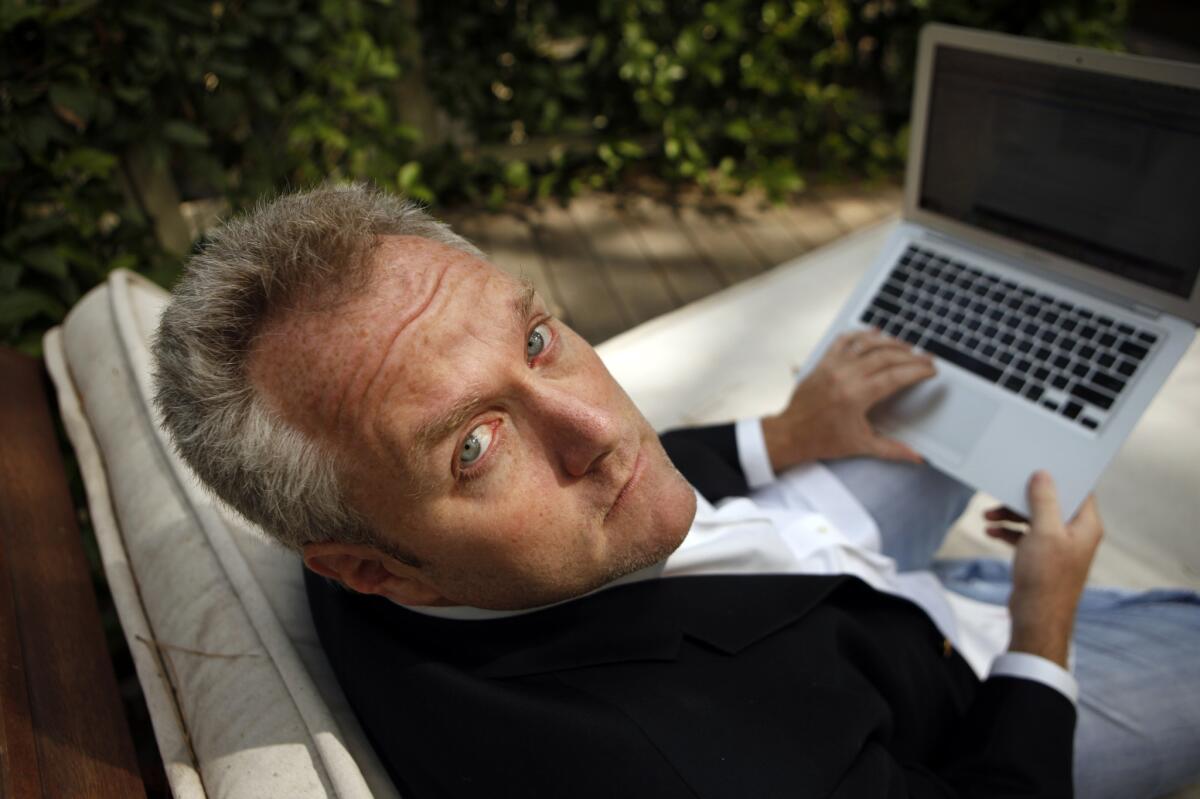

Andrew Breitbart dies at 43; conservative Internet entrepreneur who took on the left

Andrew Breitbart, the pugnacious, conservative Internet entrepreneur who took on the left and what he called the “media bully cabal” with a series of exposes that were explosive and sometimes flawed, died early Thursday after collapsing near his home in Westwood. He was 43.

According to his father-in-law, actor Orson Bean, Breitbart, a father of four, was out for a late-night walk shortly after midnight when he apparently suffered a heart attack. Paramedics took Breitbart to Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, Bean said, but he could not be revived.

FOR THE RECORD:

Andrew Breitbart: An obituary of conservative Internet entrepreneur Andrew Breitbart in the March 2 LATExtra section misspelled media law expert Michael Rothberg’s last name as Rothbert. —

Breitbart could be harsh at times, but he also had a magnetic personality that even many of his adversaries found appealing. He was a hero to conservatives, especially those who embraced the “tea party” movement, whom he passionately defended against charges of racism. To liberals, he was a reckless provocateur, blinkered by his late-blooming hatred of the left.

His biggest coup came in May of 2011 when he revealed that U.S. Rep. Anthony Weiner (D-N.Y.) had been sending salacious photographs to women online. At first, Weiner said that his Twitter account had been hacked. He later admitted his misbehavior and apologized to Breitbart.

As Weiner was about to face the press in New York, Breitbart stepped up to the microphones. “I’m here for some vindication,” he said. Breitbart’s bestselling 2011 memoir was titled “Righteous Indignation: Excuse Me While I Save the World.”

Breitbart recognized the power of the Internet early. Schooled at the feet of two other L.A.-based Internet sensations, Matt Drudge and Arianna Huffington, he applied lessons gleaned while toiling in the background for them when he launched Breitbart.com.

The site evolved into several topical sub-sites focused on journalism, government and Hollywood, all aimed at promoting Breitbart’s war on the liberal agenda.

“In the first decade of the Drudge Report, Andrew Breitbart was a constant source of energy, passion and commitment,” Drudge wrote in a note to readers. “We shared a love of headlines, a love of the news....I still see him in my mind’s eye in Venice Beach, the sunny day I met him.”

Huffington, editor-in-chief of the Huffington Post Media Group, recalled Breitbart’s “passion, his exuberance, his fearlessness.”

GOP presidential candidates Rick Santorum, Mitt Romney and Newt Gingrich all paid tribute on Twitter. Former Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin said on Facebook that Breitbart was “a warrior who stood on the side of what was right.”

Eric Boehlert, senior fellow at the liberal Media Matters for America, was a frequent Breitbart antagonist.

“Breitbart was one of the first on the conservative side that really did understand what the Internet could do for the conservative movement and was certainly able to harness that,” Boehlert said. “He was a charismatic figure, there’s no question about that. There was a star presence about him.”

Breitbart launched his site in 2005. Four years later, he posted a series of undercover videos by a young conservative activist, James O’Keefe III.

The videos targeted the community group ACORN and showed O’Keefe and a female partner asking ACORN workers for financial advice for a business with underage prostitutes. What they did was hailed by conservatives for exposing wasteful taxpayer spending and ripped by liberals as entrapment. Congress later de-funded ACORN.

“Andrew was a colorful and magnetic personality, as humorous as he was passionate,” O’Keefe said in a statement.

When he showed his video footage to Breitbart, O’Keefe said, “He told me the establishment would call the actions of the employees in the first tape an isolated incident. ‘We’re going to embarrass the media if they try to cover this up,’ he told me.”

Breitbart stumbled in the summer of 2010, when he posted a deceptively edited video purporting to show racist statements by an obscure African American government official named Shirley Sherrod. Sherrod, whose story actually illustrated how she overcame feelings of racism to help a white farmer save his land, was fired. Embarrassed, the Agriculture Department offered her a new job. She sued Breitbart for defamation. (Attorney Michael Rothbert, an expert on media law, said Sherrod could sue his estate.)

“My prayers go out to Mr. Breitbart’s family as they cope during this very difficult time,” Sherrod said in a statement.

As befits a creature of the new media world, Breitbart’s favorite tool for attack was Twitter. After Sen. Edward M. Kennedy (D-Mass.) died in 2009, Breitbart tweeted that Kennedy was a “villain,” a “duplicitous bastard” and worse.

Yet many Breitbart critics found his exuberant personality hard to resist.

Writer and blogger Andrew Sullivan, who sparred with Breitbart, recalled that when he found himself sitting next to Breitbart last fall on a flight to Los Angeles, they swapped music picks. “I happen to personally like him,” Sullivan wrote at the time, almost sheepishly.

Breitbart was born Feb. 1, 1969, and grew up in Brentwood with secular Jewish parents who adopted him and his younger sister, Tracy. He attended two exclusive private schools, Carlthorp and Brentwood. His father, Gerald, owned a landmark Santa Monica restaurant, Fox and Hounds. His mother, Arlene, was a bank executive.

He attended Tulane University and became a passionate consumer of what he called “girly drinks” and 1980s British alt-rock. “The music sort of meshed with my philosophical angst,” Breitbart told The Times in 2010. “I would say I was a shallow nihilist.”

As a young adult, he said, he had three epiphanies that turned him from a “rollerblading, gallivanting, jocular goofball” into a conservative.

He was appalled in the late 1980s when his childhood best friend and business partner, Larry Solov, told him that Stanford University had a voluntarily segregated black dormitory; he was furious at the 1991 grilling of Clarence Thomas during his Supreme Court nomination hearings; and he was annoyed that some in the media had anointed Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain as the “spokesman” of Breitbart’s generation.

“I just started to have the awkwardly pedestrian revelation that my parents were right,” he said.

Breitbart relished living as the enemy in the liberal bastions of Los Angeles and Hollywood, where he was supremely at ease, having married into a Hollywood family, and spent many hours at Huffington’s famous salon with the industry’s bright lights.

He loved to shock conservatives, too.

In January, he was a guest of commentator Tucker Carlson’s at a Chicago fundraising dinner hosted by former Weather Underground radicals Bill Ayres and Bernadine Dohrn.

Breitbart told Fox News that Ayres was a wonderful host and cook.

“This is one of the ways they’re able to indoctrinate young impressionable people,” Breitbart said. “They’re so charming, so good at throwing the best possible party. At the end of the day, it’s no wonder they’re able to get kids to say, ‘Hey, let’s do bombs against the Pentagon.’ ”

In addition to his parents and sister, Breitbart is survived by his wife, Susannah, and their four children, Samson, 12; Mia, 10; Charlie, 6; and William, 4. The family has not announced memorial arrangements.

Times staff writers Rong-Gong Lin II and Andrew Blankstein contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.