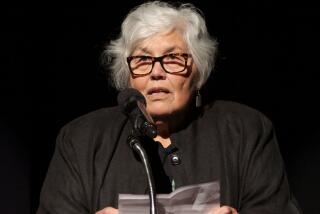

Chavela Vargas dies at 93; preeminent <i>ranchera</i> songstress

MEXICO CITY — Chavela Vargas, a preeminent interpreter of the music of loss and longing known as ranchera, who defiantly shattered gender stereotypes and blazed a legendary path through 20th century Mexican popular culture, has died. She was 93.

Vargas died of multiple organ failure Sunday at the Hospital Inovamed in Cuernavaca, Mexico, according to a spokeswoman there. Vargas had been hospitalized for a number of days after returning from Spain, where she had been promoting a CD dedicated to Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca.

Though Vargas experienced her first flush of fame in the mid-20th century — with an outlaw image she cultivated by wearing men’s clothing, packing a pistol and knocking back copious quantities of tequila — she enjoyed a second round of admiration that was perhaps even more intense beginning in the 1990s, with a rediscovery fueled in great part by Spanish filmmaker Pedro Almodovar, who championed her music for a new generation and included it in some of his films.

It was Almodovar who perhaps best described Vargas’ chosen instrument as “la voz aspera de la ternura” — the rough voice of tenderness.

Isabel Vargas Lizano was born April 17, 1919, in the town of San Joaquin de Flores in Costa Rica and had hoped to be a musician from her early childhood. In the 1930s, after the divorce of her parents and a childhood she described as unhappy, she relocated to Mexico, where she took a number of odd jobs and eventually dedicated herself to singing.

By the 1950s she had become a fixture on Mexico City’s thriving bohemian club scene, where she became a standout for her androgynous style and overt references to her homosexuality — which she would not make public until 2000 — but also for her undeniable talent for finding the soulful pith in the rancheras, boleros and corridos of the day.

Often accompanied by stark, minimal guitars, Vargas’ voice could shift expertly between jarringly different moods, often within the brackets of a single song — from intimately confessional to brightly hopeful to searingly wounded. The late Mexican essayist Carlos Monsivais wrote that Vargas knew “how to express the desolation of the rancheras with the radical nakedness of the blues.”

Along the way, she mingled with the cream of Mexico’s artistic and intellectual set, including writer Juan Rulfo, composer Agustin Lara, and the painters Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo.

It was long rumored that the bisexual Kahlo and Vargas engaged in a romantic affair. In 2009, the Los Angeles Times reported that a diary purportedly belonging to Kahlo described the painter’s intense — but unrequited — attraction to the singer.

Vargas recorded her first record, “Noche de Bohemia,” in 1961 and went on to record more than 80 others. Her versions of songs like “La Llorona” (The Weeping Woman) and “Piensa en Mi” (Think of Me) are considered definitive.

By 1976, a life lived as hard as she had described in her songs had caught up with her, and she largely disappeared from public life until the 1990s, when she was rediscovered by a new generation of fans. In 2002, she appeared in the biographical Kahlo film “Frida,” in which she sang “La Llorona.” In 2007, she was awarded a Latin Grammy for a career of musical excellence.

Her late-in-life coming out was not much of a surprise to anyone who had followed her career: She often declined to change the pronouns in love songs written by men from “she” to “he.” But she also tended to shun modern gender pigeonholes, noting that many described her as “rareza” — a rarity.

In recent years, a number of younger artists acknowledged their debt to Vargas’ style, including Spanish singer Concha Buika, who won a Latin Grammy for best traditional tropical album with her tribute to Vargas, “El Ultimo Trago” (The Last Drink).

In a 2010 interview with the Miami Herald, Buika said Vargas taught her to “make a monument out of loneliness.”

“This is what I learned from Chavela,” she told the paper, “that loneliness is the best and most liberating of companions.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.