Healthcare reform and the incentive to keep spending

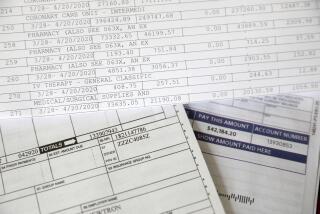

Reforming the healthcare system is largely about fixing the incentives it provides for doctors, hospitals and patients to overspend. For example, the “fee for service” payment model that Medicare relies on encourages physicians to do as many things for a patient as they can bill for -- the more services provided, the higher the compensation. That’s a model that profits from sickness, not health.

House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) made a similar point in his latest budget proposal about Medicaid, the health insurance program for the poor that’s jointly funded by federal and state governments.

“Medicaid’s current structure gives states a perverse incentive to grow the program and little incentive to save,” Paul wrote in a report that accompanied his proposed budget. “The federal government pays an average of 57 cents of every dollar spent on Medicaid. Expanding Medicaid coverage during boom years can be tempting for state governments since they pay less than half the cost. Conversely, to restrain Medicaid’s growth, states trying to rescind a dollar’s worth of coverage only save themselves 43 cents.”

I’m not sure states lack the incentive to save, considering how much lawmakers in Sacramento have cut Medi-Cal (the state’s version of Medicaid) in recent years. Nevertheless, they certainly have an incentive to maximize the amount of federal dollars they receive and spend.

Here’s one example. The Brown administration announced Tuesday that it had reached agreement with labor unions and Medi-Cal beneficiaries to resolve two class-action lawsuits related to cuts in the In-Home Supportive Services program, which pays people to care for impoverished elderly and disabled Californians in their homes. Care providers and beneficiaries brought one of the lawsuits in 2009 to stop in-home workers’ pay from being cut by 16%, and the other one in 2011 to preempt a 20% across-the-board cut in the program.

Under the settlement, the plaintiffs agreed to accept an 8% cut in the program in the coming fiscal year, and the Brown administration agreed to restore at least some of the money in subsequent years. The key to that restoration is for the state to collect as-yet unspecified fee from healthcare providers, including in-home supportive services workers.

The fee, which would have to be approved by Washington, would accomplish two things. First, it would allow the state to spend more on in-home supportive services without taking more money out of the General Fund. And second, because the federal government matches every dollar the state spends on Medi-Cal with a dollar from the Treasury, it would bring more federal dollars in to help pay for in-home services (depending, of course, on the federal government’s acquiescence in the plan).

Although some critics claim the in-home supportive services program is rife with abuse, it saves the state an enormous amount of money over the long term to care for ailing Medi-Cal beneficiaries in their homes instead of in a hospital or nursing home. And the number of poor Californians who’ll need long-term care is expected to grow as the baby boom generation reaches its dotage, vastly increasing the population of retirees.

Clearly, the state has to find ways to keep Medi-Cal from draining the General Fund. The in-home services settlement shows how tempting it is to find savings by coming up with new ways to tap the federal Treasury, rather than actually reducing the cost of keeping Californians healthy.

ALSO:

Low expectations for Obama’s Israel visit

L.A. Marathon: Angry drivers vs. elated runners

The Traditional Values Coalition gives Rob Portman hell

Follow Jon Healey on Twitter @jcahealey

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.