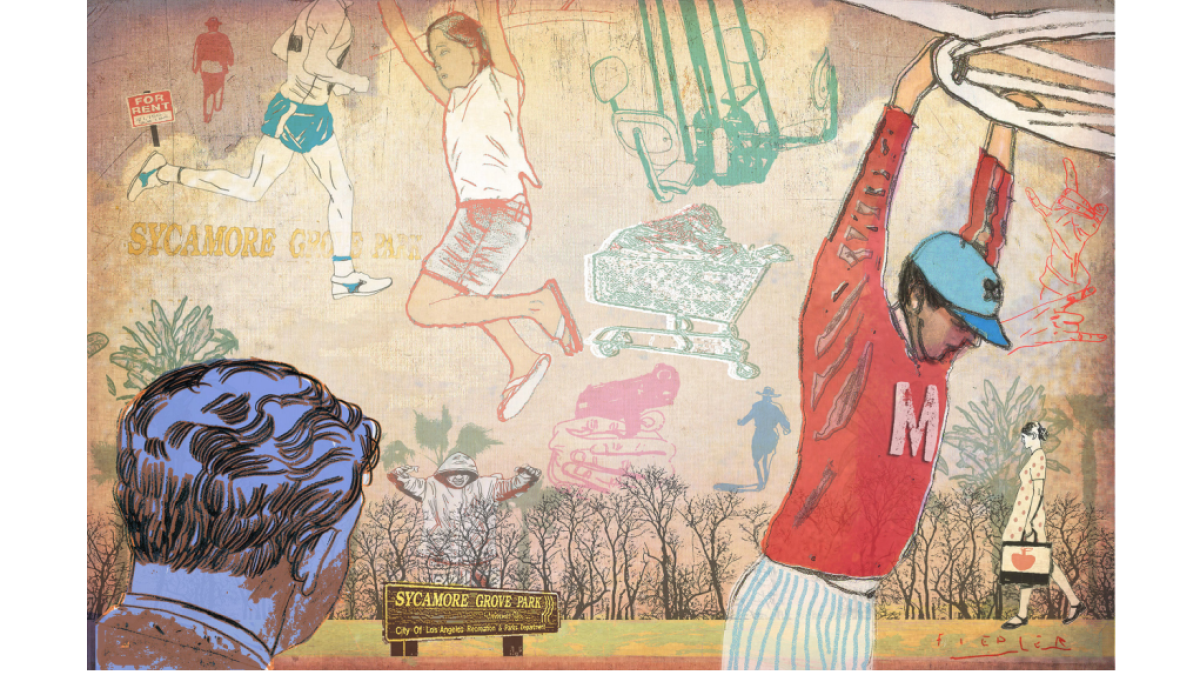

Op-Ed: A change in the landscape: L.A.’s parks no longer belong to street gangs

At Sycamore Grove Park in Highland Park a few weeks ago, I met a 32-year-old bank teller named Uscolia Flores. She’s lived most her life within walking distance of this 15-acre park, which winds along between the 110 and Figueroa Street.

------------

FOR THE RECORD:

Parks: A Feb. 8 Op-Ed about gangs and parks stated that Smith Park is in Alhambra; it is in San Gabriel.

------------

Back when Flores was in her teens, local gang members took it over as a hangout. They congregated toward the back of the park in ever-larger groups, drinking beer and ready to face off with any rival who happened by. You never really knew what was going to happen. Most families avoided Sycamore Grove. Flores said she didn’t visit the park for years.

Two weeks ago, however, she was there, watching her 4-year-old play on a jungle gym. She and her son are beneficiaries of what can properly be called a revolution across Southern California.

In the last few years, gangs have receded from streets and public areas they once dominated. Indeed, in the region that invented the phenomenon, it’s probably no longer correct to talk about “street” gangs.

Gangs still exist here. They’re involved in drug trafficking, identity theft, smash-and-grab jewelry heists, burglaries. But the daily degradation and intimidation of whole neighborhoods — the carjackings, graffiti, shootings and, of course, the constant hanging out — is no longer central to how they operate.

Parks are among the best places to size up the scope of this change. Roosevelt Park in Florence-Firestone; Smith Park in Alhambra; Patterson Park in Riverside; Salvador Park in Orange County; Plaza Park in San Bernardino; and the mother ship, MacArthur Park, west of downtown — all these and many more were notorious gang hangouts. Today they have been returned to their rightful owners: neighborhood residents like Flores and her son.

For years, gangs in parks inflicted a special kind of torture on working-class neighborhoods. Residents were often crammed into houses or apartments that were too small. Respite at a nearby park was out of the question when the picnic tables were dominated by gang members with their beer cans and pit bulls.

Now families flock there, and nearby houses are appreciating in value. It’s a barely noticed yet radical change, and its benefits redound mostly to working-class families.

This shift is important beyond providing access to more outdoor space. Parks were part of the primordial soup from which gangs emerged here. Parks were open areas where members could be the occupying force that police could not. Several gangs took their names from nearby parks. Establishing a presence in them added to a gang’s reputation. Because members were out in the open, some parks became crime magnets — places where shootings happened and long-running feuds could erupt.

In the 1990s, when the Mexican Mafia prison gang imposed a truce between feuding Latino gangs and instituted a system in which gang members “taxed” local drug dealers, the meetings happened in parks in Chino, San Bernardino, Santa Ana, South El Monte, Pacoima and Echo Park, to name a few.

After that, Latino gangs undertook a kind of ethnic cleansing in many of the surrounding neighborhoods, attempting to rid their areas of black people, whether they were affiliated with a gang or not. That terror was often spread at parks. Pacoima’s Humphrey Boyz gang made the Hubert Humphrey Memorial Recreation Center — Humphrey Park, as it’s known — off-limits to blacks for several years, according to residents and members of that gang I have interviewed. In Montecito Park, just across the 110 from Sycamore Grove, Avenues gang members staged assaults against black Highland Park residents; federal prosecutors convicted four of them of violating hate crime laws in 2006.

Those days are gone.

What changed? The business imperatives in the gang and drug-trafficking underworld, for one thing. The focus is now on making money. Tit-for-tat shooting feuds that were so much a part of street gang life attract police attention and are now frowned upon. Why risk business over petty street beefs?

New families, with no gang connections, are moving into traditional gang areas as old families depart. Kids spend far more time indoors on the Internet and less time on the street.

Better policing strategies are a big part of the story. Federal racketeering indictments and CompStat, the data analysis of crimes and where they happen, have proved effective. Gang injunctions have sent many gangs indoors or at least elsewhere.

The Los Angeles Police Department also underwent a profound change over 20 years, embracing community policing and becoming more racially diverse. Officers now cultivate alliances and partnerships with residents in a way impossible to imagine a generation ago — and that combats much of what had atomized neighborhoods and allowed gangs to flourish. Officers have fostered neighbors’ confidence in reporting crimes. They’ll call a city crew to remove a discarded sofa.

Other law enfocement has followed suit.

In 2010, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department brought this philosophy to parks. It formed a bureau to take over patrolling of 174 parks around the county from the Office of Public Safety. Deputies were assigned specific parks. With accountability and consistent deputy presence, problem parks — in Lennox, Lynwood, Lancaster — are now safe for families.

At Sycamore Grove Park, the city put in new jungle gyms a few years back. It also installed workout equipment, so, without the presence of gang members, locals now have what amounts to a health club with no membership fee.

Still, I guess nothing comes for free.

Sycamore Grove is also where you can see another unexpected effect of the absence of gangs: a rise in the number of homeless people. You can usually see a few guys pushing shopping carts along the park and sleeping on the grass at midday.

Omnipresent street gangs kept rents low more effectively than any ordinance. Who’d pay market rates to live in a gang neighborhood? What landlord wanted to invest in a property while thugs lurked down the street? Now rents are on the rise in Highland Park, and so is homelessness.

Uscolia Flores said that in the last three years, her mother-in-law’s rent went from $600 to $989.

“You get rid of one thing,” she told me, as I was leaving, “but then you struggle with another.”

Sam Quinones is a journalist based in Los Angeles. His third book, “Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic,” comes out in April.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.