Op-Ed: The border crisis isn’t a partisan issue. It’s real, and children are in danger

Immigration has become such a partisan issue, it’s sometimes hard to separate fact from fiction. But here’s something that’s undeniably true: We have a dangerous crisis at our southern border.

It is the result of a sharp and unprecedented increase over the last year in the number of family units from Central America, mainly Guatemala and Honduras, illegally crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. Nearly all of these family units are one adult with a single child, and an increasing number of them, nearly half, consist of a man and a child. Almost three-quarters of the children are age 12 or younger.

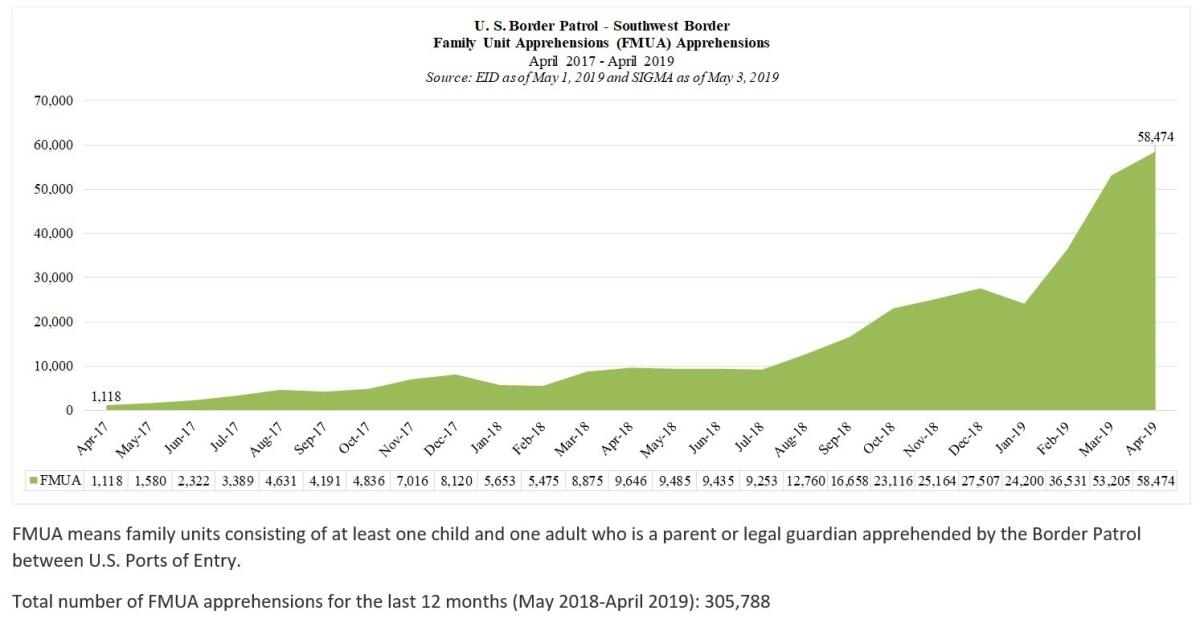

The surge in family unit migration is breathtaking. In April 2018, just over a year ago, the Border Patrol apprehended 9,646 people traveling as family units. In April this year, 58,474 people in that category were apprehended. That is a 500% increase year over year. Unless something is done, we can expect some 500,000 families to be apprehended this year.

Children making the treacherous journey, even with a parent or guardian, are at great risk for multiple medical problems, including dehydration, malnutrition, infections, psychological trauma, physical injuries and all manner of mistreatment. And too often, the children are being used as pawns by adults to gain entry into the U.S.

Over the past five months, we both served on a bipartisan task force of the Homeland Security Advisory Council, and we traveled to the border multiple times, visiting ports of entry from San Ysidro, Calif., to Brownsville, Texas. We saw firsthand the dangerous areas where, after harrowing 1,500- to 2,000-mile journeys through Mexico, criminal smuggling organizations abandoned the families they guided in remote, desert areas. We saw where smugglers pushed young children through razor wire not far from Yuma, Ariz. We saw families pile into rickety rafts to illegally cross the Rio Grande.

The Border Patrol’s temporary holding areas were never designed for children, yet they are now packed to the rafters with families. The Department of Homeland Security lacks space to house and shelter them as it processes asylum claims, so after a day or two in Border Patrol custody, most of the family units are given “notices to appear” and dropped off at bus stations or at overwhelmed nonprofit shelters. We know of no other industrialized nation that handles potential asylum seekers in this way.

Only a small percentage of the migrants who apply for asylum will ultimately qualify for it, but the fact that they are released with no more than an easily severed ankle bracelet — and that it currently takes several years to adjudicate a claim — has created a powerful magnet that is being exploited. When a family’s asylum claim is denied, as most Central American claims ultimately are, migrants often remain in the U.S. illegally, where the odds of getting caught are very low.

The dramatic increase in family unit migration over the past 12 months is directly linked to policies of the U.S. government that have incentivized migrants to bring children with them. And dealing with the surge has crippled the agency’s ability to capture others seeking to evade it. As a result more migrants attempting to sneak in are making it past the Border Patrol.

One factor exacerbating the problem is that U.S. law does not require asylum-seekers to file their claims at official ports of entry, which means criminal smuggling groups can drop families at dangerous areas of the border and leave them to make their way into the U.S. to find a border officer to surrender to. Another problem is that, as a result of a federal court decision in the case of Flores vs. DHS, the Department of Homeland Security can only hold families with children for short periods, generally no more than 20 days, even though screening for infectious diseases, verifying parentage, checking on criminal history and conducting initial asylum interviews can take longer than that.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute »

Our task force recently proposed emergency recommendations to address the crisis, including promptly erecting three or four regional processing centers for families near the border, or even before they get to the United States. We proposed that one should be put in Guatemala, near the Mexico border. These regional centers could provide safe, sanitary shelters where some steps of the asylum process could be completed.

To avoid the need for long-term detention, we call for faster asylum processing, including a substantial increase in immigration judges and the co-location of these judges and asylum officers at the regional processing centers.

Some of our other recommendations include emergency legislation to limit the Flores decision to what it originally covered: unaccompanied children. We also propose requiring asylum seekers to make their claims at U.S. ports of entry and greatly expanding capacity for processing families there to put an end to long waits.

These realistic and compassionate measures are urgently needed to protect the welfare and safety of children brought by adults and smuggling organizations. Ever increasing numbers of children will be put in danger until our proposals are adopted.

James R. Jones, a retired seven-term congressman (D-Okla.), was U.S. ambassador to Mexico under President Clinton. Robert Bonner is a former U.S. District Court judge and former commissioner of Customs and Border Protection under President George W. Bush. They both served on the Homeland Security Advisory Council task force on families and child care.

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.