Column: In Iraq, closing the gap between Obama’s goal and means

Discordant notes from the Obama administration last week were widely interpreted as a collision between a war-weary president and a gung-ho military. And it was easy to see why.

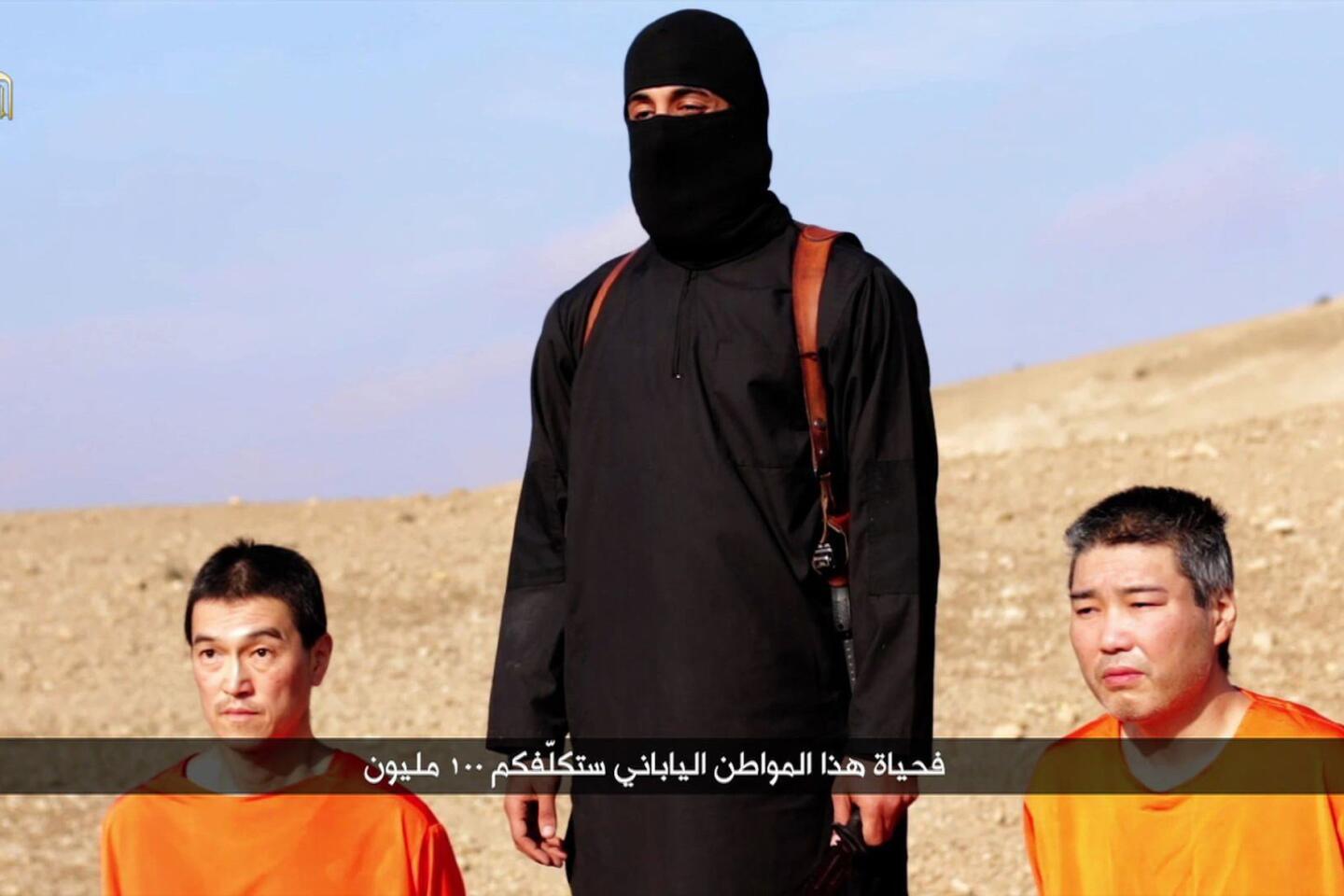

President Obama ordered airstrikes against Islamic State militants, but promised that no U.S. ground troops would enter the fray. “The American forces deployed to Iraq do not — and will not — have a combat mission,” he vowed.

Then Army Gen. Martin Dempsey, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said he might ask Obama for authority to send U.S. military advisors into battle with Iraqi units. “If we reach the point where I believe our advisors should accompany Iraqi troops on attacks against specific ISIL targets, I’ll recommend that to the president,” the general said, using the government’s acronym for Islamic State.

And he went even further: “There will be circumstances when we think that will be necessary,” he predicted. “But we haven’t encountered one yet.”

Does this mean we have a serious divide between military brass and their commander in chief?

Not necessarily — at least, not yet.

Part of the issue is semantic. When Obama said “no combat mission,” he meant U.S. troops wouldn’t be firing weapons on the ground. But in the eyes of the military, a forward spotter who calls in airstrikes is on a combat mission, even if he never fires a shot. And U.S. pilots over Iraq are already on combat missions, even though Islamic State doesn’t have an air force

Moreover, the president and the general approached the problem from different starting points.

The president, selling a new military offensive in a region Americans had hoped to leave, had every reason to emphasize the limits of his commitment.

He announced an ambitious goal, to “degrade and ultimately destroy” Islamic State, but he also announced a limit to what he’s willing to invest in that mission, right up front.

That’s partly politics — but it’s also a reflection of Obama’s abiding fear of being lured onto a slippery slope of military escalation. He still wants to be seen as a president who ends wars, not starts them.

Dempsey, by contrast, started by looking at the mission — defeating Islamic State — and worked backward from there, calculating what is needed to accomplish it. He said his hope is to succeed with the president’s Plan A: providing airstrikes, intelligence, equipment and advice to help Iraqi forces dislodge Islamic State on the ground.

But if the Iraqis fall short, Dempsey and his colleagues want the men and women under their command — as well as the American public and Islamic State — to know they reserve the right to propose using U.S. forces, including special operations teams, if that could change the outcome.

On at least one issue, the White House and the generals are in sync. Dempsey said he has no interest in large-scale deployment of U.S. combat units in Iraq.

“We don’t want them to become dependent on us,” he explained.

Still, there’s an echo here of the administration’s battles of 2009, when the generals proposed sending more troops to Afghanistan, and Obama felt he was being publicly pressured to agree. As a result, the president turned “deeply suspicious of their actions and recommendations,” his secretary of Defense at the time, Robert M. Gates, wrote later. Aides insist that isn’t happening now.

Even if it were, the dueling statements of the president and the generals are a sideshow. A far more important issue is whether there is a mismatch between Obama’s ambitious goal and the limited means he is willing to invest in it.

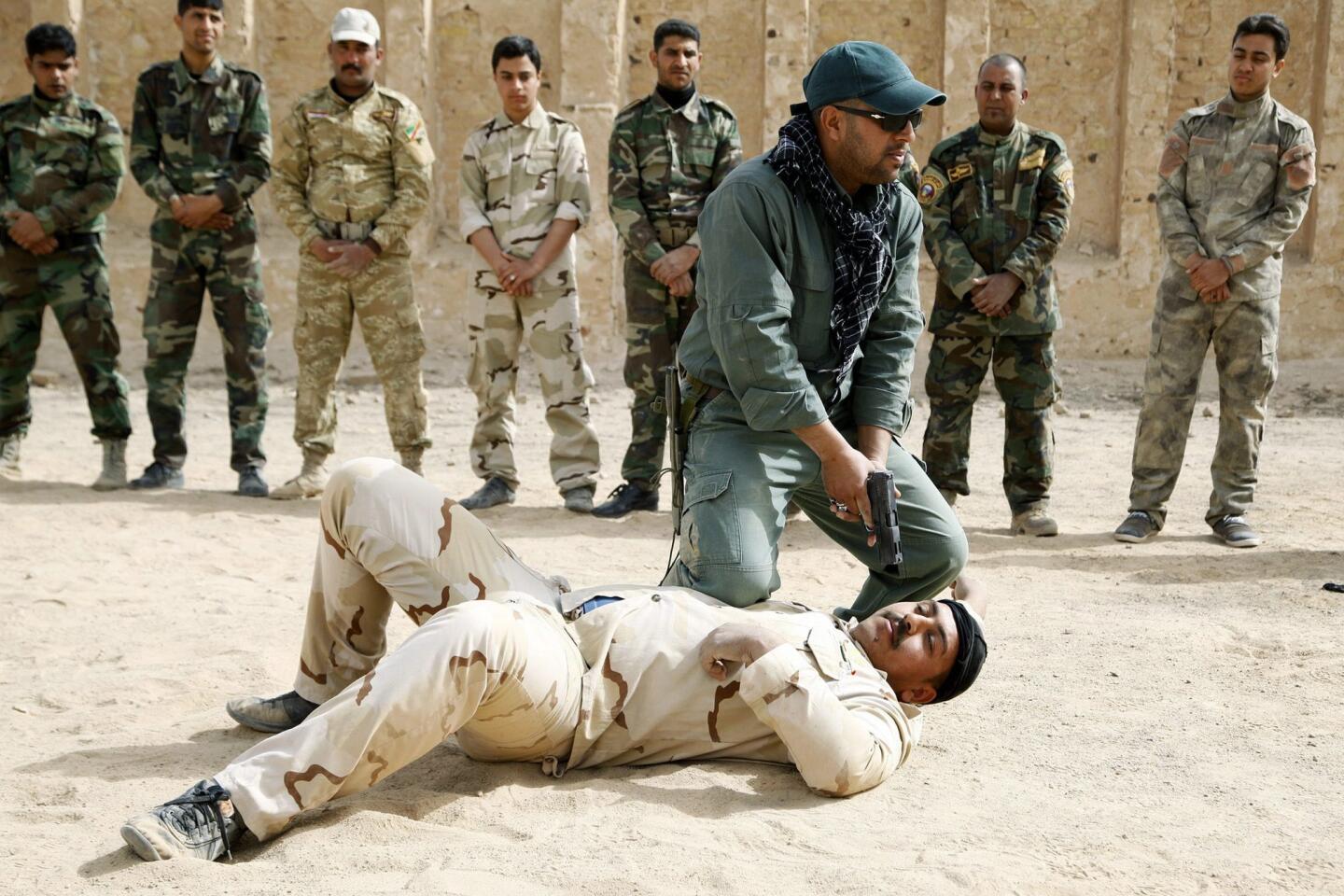

The U.S.-led campaign in Iraq is giant, high-stakes experiment. Can limited U.S. support really turn the same Iraqi security forces that crumpled last summer into an effective fighting force capable of evicting the militants from the land they seized? Will other Arab countries, including Saudi Arabia, provide enough support to make the coalition real and win the allegiance of Sunni Iraqis to the Baghdad government’s side?

It’s easier to find skeptics than optimists.

“We have almost 2,000 troops there now; to achieve these goals, I think that number is going to need to grow to 10,000 or so,” warned retired Adm. James Stavridis, dean of the Fletcher School at Tufts University. “I don’t think

we can foreclose the option of direct U.S. combat force being applied.”

“To promise that we’re going to destroy ISIS or ISIL sets a goal that may be unattainable,” Gates said in a television interview last week. “By continuing to repeat that [no U.S. forces will engage in combat], the president, in effect, traps himself.”

If Plan A doesn’t work, Obama will be forced to close the gap between his ambitious goals and his limited means. That means either escalating U.S. military involvement and stepping onto the slippery slope he fears, or reducing the goal to the more realistic target he incautiously proposed last month: “to shrink [Islamic State] to the point where it is a manageable problem.”

doyle.mcmanus@latimes.com

Twitter: @DoyleMcManus

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.