The International Criminal Court’s risky move

- Share via

The Kenyan parliament’s recent vote to withdraw from the International Criminal Court could undermine the trials of Kenya’s president and deputy president. But even more alarming, the vote casts a shadow over the ICC’s global mandate to effectively prosecute those responsible for state-sponsored atrocities.

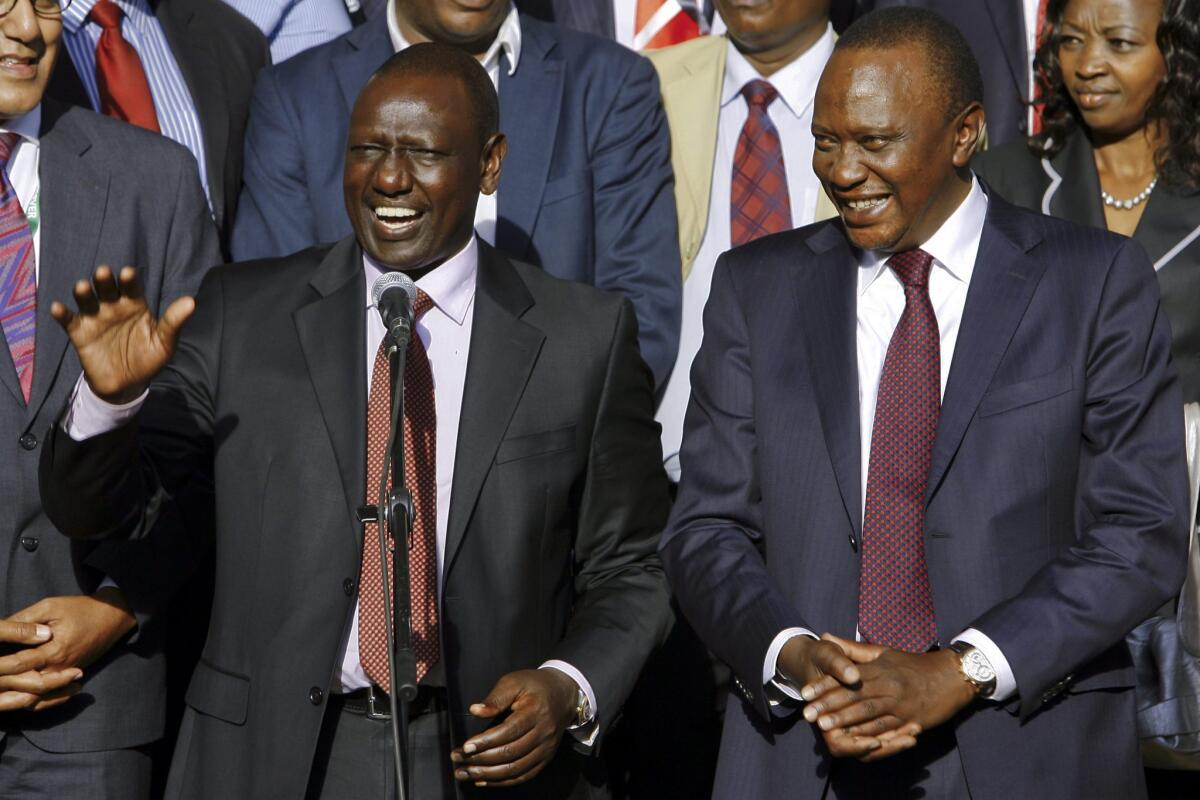

Kenya’s final decision on withdrawing from the court will rest with President Uhuru Kenyatta, whose trial is scheduled for November, and Deputy President William Ruto, whose trial began last week. Both men are charged with crimes against humanity in connection with their alleged role in massacres after the 2007 Kenyan elections. Both have said they are not guilty.

If Kenya follows through on its threat, it could potentially trigger withdrawals by other African members of the ICC, which have long been dissatisfied with what they see as the court’s singular focus on African crimes. The ICC has opened formal investigations in eight African countries but none in other conflict zones — such as Afghanistan — that lie in the court’s jurisdiction. Even though 34 African countries have ratified the ICC’s statute, many African leaders now see the 11-year-old court as anti-African.

At Kenyatta and Ruto’s inauguration in April, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, who a decade earlier referred the first case to the ICC, congratulated Kenyans for their courage in electing the two ICC indictees and chastised the West for using the court “to install leaders of their choice in Africa and eliminate the ones they do not like.” Weeks later, Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn accused the ICC of racist bias and “hunting Africans.”

If Kenya and other African states head for the exit, it would deal a severe blow to the ICC. Member states provide funding and logistical support and serve to legitimize the ICC’s campaign for universal membership. Moreover, without a police force of its own, the ICC is at the mercy of states to provide safe access to crime scenes, protect witnesses and arrest and hand over fugitives.

That Kenyatta and Ruto are using every means at their disposal to evade accountability is nothing new. Over the last two decades, international indictees have developed ingenious strategies to avoid arrest and obstruct justice. But Kenyatta and Ruto have taken the obstruction of international justice to a new level.

On the one hand, they have honored ICC summonses and appeared for pretrial hearings. On the other, both have launched a multi-pronged offensive to undermine the ICC as an institution.

The court’s chief prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, alleges that the scale of interference with witnesses in the Kenyan cases has been “unprecedented.” Over the last year, relatives of witnesses have been continuously approached with bribes and threats intended to motivate disclosure of witnesses’ whereabouts. And in recent weeks, several key witnesses in the Ruto case have said they will not testify against the Kenyan leaders, citing family pressures and security concerns.

Kenyatta and Ruto have also deftly exploited their ICC indictments to rally nationalist sentiment. In the months before the hotly contested presidential election this year, Kenyatta, whose father led Kenya’s independence movement and was the country’s first president, portrayed the ICC as a tool of Western governments. U.S. diplomat Johnnie Carson, anticipating a potential Kenyatta victory, added fuel to the fire by warning Kenyan voters that “choices have consequences.” That warning backfired as pro-Kenyatta surrogates-cum-pundits seized the opportunity to question American motives at this critical juncture in Kenya’s history.

Beyond Kenya’s borders, the ICC indictees have sought and received the support of their African counterparts. At an African Union summit in the spring, African leaders called on the ICC to refer the cases against Kenyatta and Ruto to a Kenyan court, a move ICC judges later rejected, citing security concerns for witnesses.

For its part, Kenya has been generous with its support for Sudanese leader and ICC fugitive Omar Hassan Ahmed Bashir. At a 2009 African Union summit in Libya, Kenya voted for a resolution calling on AU states not to cooperate with the ICC’s efforts to prosecute Bashir and criticizing the “publicity-seeking approach” of the ICC chief prosecutor. A year later, Nairobi further flouted the ICC’s authority by hosting the indicted Sudanese president at a high-profile celebration of the new Kenyan Constitution. In response to a hail of criticism, a Kenyan government spokesman said that Bashir was “a state guest. You do not harm or embarrass your guest. That is not African.”

The ICC is made by states and can just as easily be unmade by states. Yet the ICC does exercise some control over whether Kenya and other African states head for the court’s departure gate. A key question is whether the prosecution can rebound from a string of botched investigations that have damaged the court’s reputation. A weak prosecution case against Kenyatta and Ruto could further their specious rhetoric that the international court is bent on undermining African sovereignty.

In the months ahead, the ICC — perhaps as much as the Kenyan leaders themselves — will be on trial in the court of international public opinion.

Victor Peskin is an associate professor at the School of Politics and Global Studies at Arizona State University. Eric Stover is faculty director of the Human Rights Center, UC Berkeley School of Law.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.