Can Democrats support a simpler tax code with lower rates?

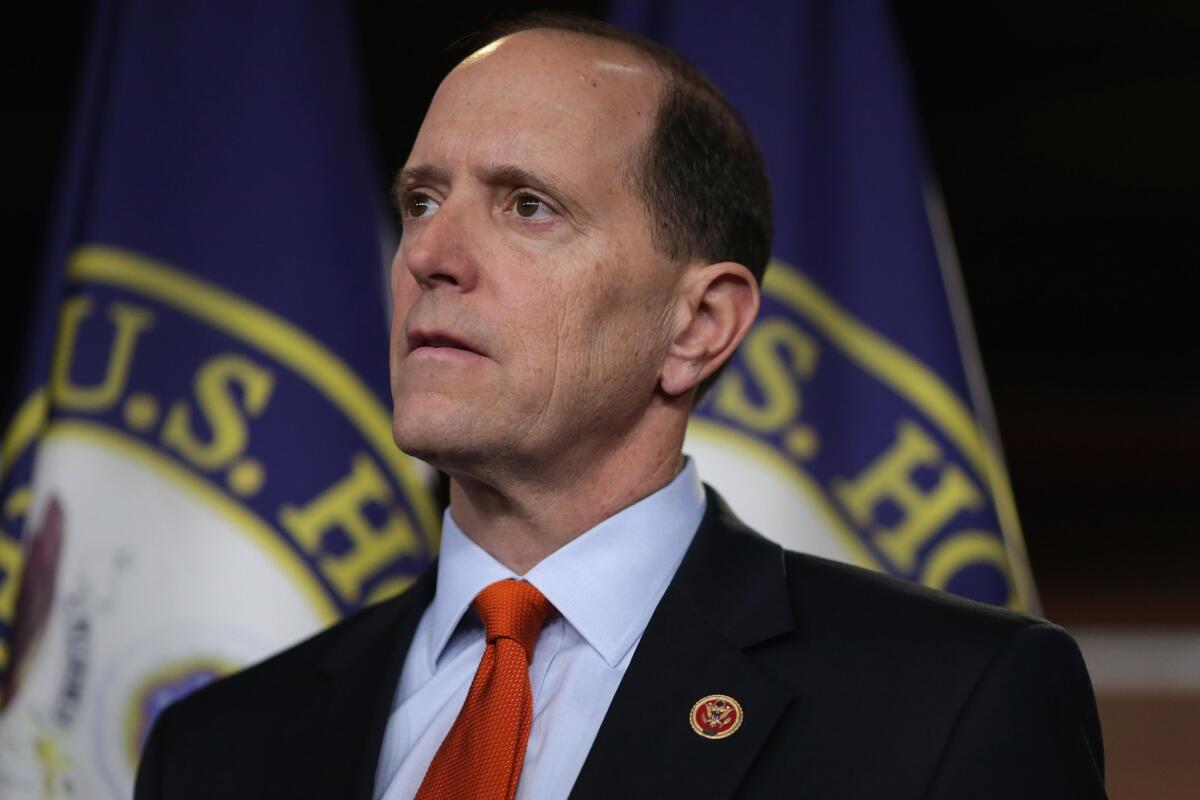

Rep. David Camp (R-Mich.), chairman of the tax-writing House Ways and Means Committee, is readying a bill to simplify the tax code by winnowing the thicket of loopholes, exemptions, credits and deductions. And who wouldn’t want a simpler tax code?

Democrats, for starters.

The problem for liberals is that they have trouble getting past the idea of lowering tax rates for the wealthy. And unless you’re trying to raise a ton of extra revenue, it’s hard to devise a tax simplification plan that doesn’t result in lower marginal rates.

The main source of complexity in the code is the special treatment given to multiple different types of revenue, expenses and investments. How much you’re taxed on the next dollar you make depends on how you arrived at that income, how many dollars you’d already made and how much of your money was spent on favored activities (e.g., charitable contributions, medical bills or business expenses).

By eliminating some of those preferences, Congress would make more income subject to taxation; tax wonks call it “broadening the base.” Lawmakers can then raise the same amount of money, or potentially more, with lower tax rates.

Camp’s bill calls for only two tax rates -- 10% and 25% -- instead of the current lineup of seven, ranging from 10% to 39.6%. But it would raise about the same amount of money overall by eliminating as-yet unidentified preferences, loopholes and deductions. It also would impose a 10% surcharge on certain types of revenue garnered by high-income Americans, including couples who earned more than $450,000.

According to the Washington Post, a “nonpartisan congressional analysis” found that “the vast majority of taxpayers would see little change in the ultimate size of their tax bills” if Camp’s proposal were enacted. That’s because deductions, exemptions, credits and preferences make higher-income taxpayers’ effective tax rates -- the amount they actually pay -- much lower than the top marginal rate. A CBO report notes that the effective income tax rate paid by the highest-earning 1% of U.S. households in the late 1990s, when the top marginal rate was 39.6%, was 23% to 24%.

If people aren’t getting a tax cut, what’s the point of reducing rates? Economists say that lower rates encourage businesses and entrepreneurs to expand and invest more, promoting faster economic growth.

All the same, cutting the top tax rate from nearly 40% to 25% seems like a nonstarter for many Democrats at a time of severe income inequality, stubbornly high unemployment and giant budget deficits. The White House seems firmly opposed to an ambitious effort like Camp’s. Officials there argue that it simply isn’t possible to broaden the base significantly without shifting more of the tax burden from the wealthy onto the middle class. Some of the costliest tax breaks, including the exemption for employee health benefits and the mortgage interest deduction, deliver huge benefits to middle-income taxpayers.

Camp hasn’t revealed which tax breaks he would curtail, with one exception. According to the Wall Street Journal, the bill would end the preference for capital gains, taxing them instead at the same rate as wages. For upper-income taxpayers, that would mean an increase from 20% to 25%. The bill would soften the blow considerably by excluding the first $40,000 in gains from taxation, which would be a particular benefit to lower-income taxpayers with smaller gains.

[Updated, 5:27 p.m. Feb. 26: The actual proposal would let taxpayers deduct 40%, not $40,000, of their net capital gains. In other words, it would tax capital gains at 60% of the rate that the taxpayer pays on ordinary income.]

It’s conceivable that Camp has massaged his bill enough to ensure that if wouldn’t make the tax code any more burdensome for any category of taxpayers than it is today, or any less progressive. That’s doable, albeit at the expense of some simplicity in the code. And while some will no doubt howl about the elimination of tax breaks that help their industries or causes, lower marginal rates could add up to $3.4 trillion to the overall U.S. economy in the coming decade, congressional economists estimate.

So there’s a powerful economic reason for both parties to embrace a bill that broadens the tax base and lowers rates while preserving progressivity in the code. It remains to be seen whether Camp’s proposal would qualify, of course. But if it does, I wonder if most Democrats can get past the notion of cutting tax rates on the wealthy, even if the wealthy still wind up paying the same amount in taxes.

ALSO:

The 2nd Street tunnel’s frustrating bike lanes

Is Benedict helping Francis downsize the papacy?

Netflix’s deal with Comcast isn’t a sign of the apocalypse

Follow Jon Healey on Twitter @jcahealey and Google+

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.