Op-Ed: How Democrats dealt with the Bernie Sanders of 1944

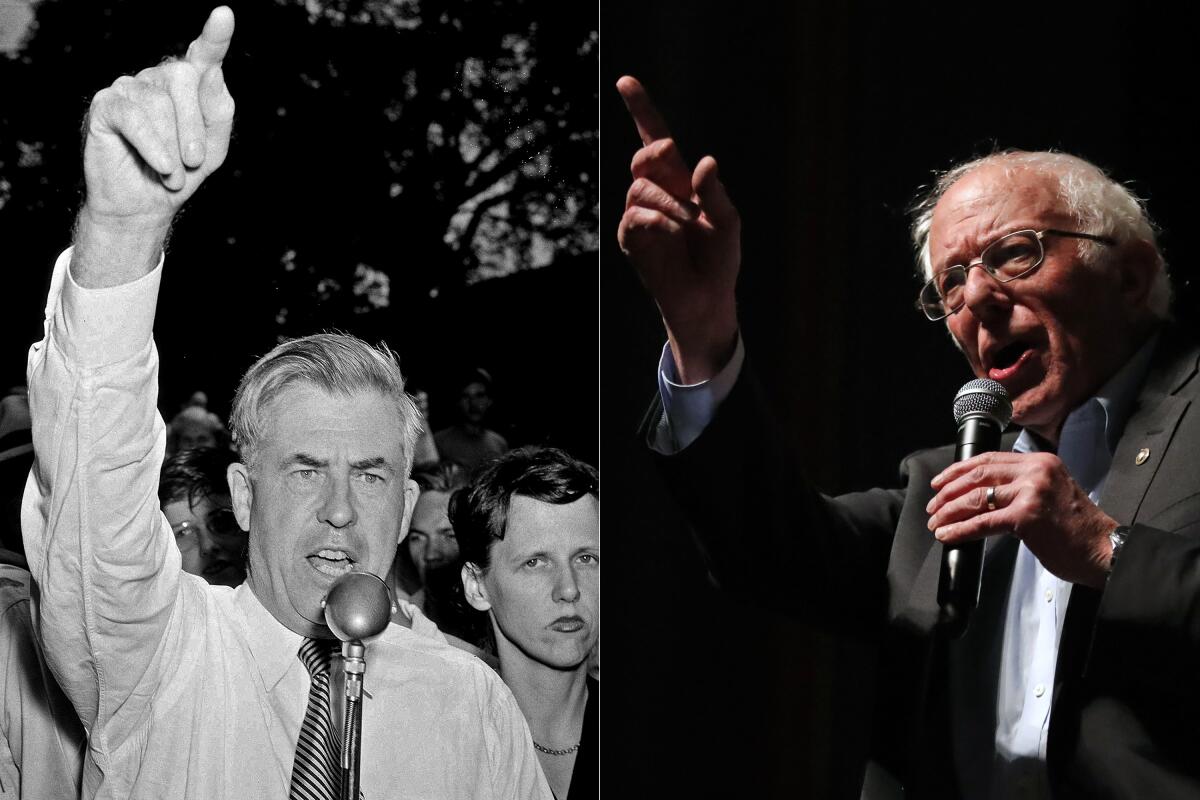

As mainstream Democrats ponder the real possibility that Bernie Sanders will be their presidential nominee, it is worth considering how the party handled a similar challenge in 1944.

The renomination of President Franklin Roosevelt for a fourth term was a foregone conclusion, but that of his vice president — the staunchly liberal and fiercely pro-Soviet Henry A. Wallace — was not. Though vice presidents have little official power beyond resolving tie votes in the Senate, they reside a heartbeat from the presidency. And though Roosevelt’s medical diagnosis was a well-kept secret (even from him), his advanced congestive heart failure was, by the spring of 1944, visible in his pallor, trembling hands and declining weight.

Party leaders were alarmed and determined to act. They considered Wallace to be both an electoral liability and a man whose views and judgment rendered him incapable of filling Roosevelt’s shoes should his health fail entirely. They couldn’t persuade the president to ditch his friend outright and anoint another running mate, but Roosevelt agreed to give Wallace the weakest of endorsements and to allow an open convention in July.

Henry Wallace had name recognition and a passionate liberal base, yet his detractors well outnumbered his supporters. But anti-Wallace Democrats weren’t able to coalesce around any one of the obvious candidates. House Speaker Sam Rayburn, Director of the Office of War Mobilization Jimmy Byrnes and Senate Majority Leader Alben Barkley were the best-known alternatives. The president liked Supreme Court Justice William Douglas. But all these men had their own electoral drawbacks.

Determined not to let the vice presidential nomination fall to a man who had, just before the convention, spent four weeks traveling around Siberia lavishing praise on Stalin, top Democratic Party officials settled on a lesser-known but electorally sound figure who had demonstrated keen political skills and policy sense: Missouri Sen. Harry S. Truman.

The case for Truman was straightforward. He was an experienced 10-year senator; respected, personable, centrist. He was a loyal New Dealer, but no radical. A border-state man, he was in the South, but not of it. He could win Dixie votes yet not lose Northern ones. Labor liked him. Black leaders liked him. Colleagues like him. Nobody loved him, but that was not in the job specs.

Democratic National Committee Chairman Bob Hannegan persuaded Roosevelt to put his willingness to run with Truman in writing. Together with DNC Treasurer Edwin Pauley, DNC Secretary George Allen and Postmaster General Frank Walker, he then set out to sell the leadership’s choice to the convention in Chicago. It was a masterful effort.

Initially, they encouraged delegates who had qualms about the Missourian as vice president to vote for their local “favorite sons.” This produced the desired result. After the first round of voting, Wallace led, but with just 37% of the 1,176 delegates. Truman garnered 27%, and the remaining votes were scattered among candidates to the right of Wallace. These votes now needed to be shepherded toward Truman.

Legend has it — a legend nurtured by serious historians (David McCullough) and fantasists (Oliver Stone) alike — that the leaders offered delegates ambassadorships or postmasterships in return for Truman votes. Yet there is no basis for it. Unbeknownst to either McCullough or Stone, the claim, I found, originated with a Wallace-supporting union lobbyist, Calvin “Beanie” Baldwin, seven years after the fact, together with the caveat that he had no evidence to back it.

In fact, the claim makes little sense. Roosevelt would never have turned over control of ambassadorial posts to party functionaries for the sake of nominating Truman, a man he barely knew. As for postmasterships, the post office had been part of the civil service since 1883; its jobs were unavailable for patronage. Instead, the Democratic leadership simply made its watertight case: The battle was now between Wallace, a man who wanted to import “economic democracy” from Russia, and Truman, a man who could help the ticket and run the country if necessary. The choice was therefore obvious.

That logic did the trick. Truman romped to the VP nomination on the second ballot, with 88% of the vote. The rest, as they say, is history. FDR won, and the Missourian became president on Roosevelt’s death the following April. Among many other great accomplishments, Truman would preside over the creation of the Marshall Plan and NATO — historic and crucial initiatives that Wallace would openly and bitterly oppose.

As for the party leaders who had orchestrated Truman’s rise in 1944, they were wholly unapologetic about their intervention.

“When I die,” Hannegan would tell a journalist a few years later, “I would like to have one thing on my headstone — that I was the man who kept Henry Wallace from becoming president of the United States.”

“It is the people who elect presidents,” Pauley reflected, “but it is the politicians who try and give them the best field to select from.” Having “become convinced that Wallace could only bring disaster to the nation and our party, [we did] our job both as citizens and practical politicians.”

In 2020, the parallels are compelling. Although democratic socialist Bernie Sanders, like Wallace in 1944, has substantial and impassioned left-wing support, a majority of Democrats appear to prefer a more moderate candidate. It is uncertain, however, that the primaries will give the one moderate remaining, Joe Biden, the 1,991 delegates required to win the nomination on the first ballot at the July convention. Delegates will then become “unbound,” and 775 superdelegates will come into play, with many Sanders supporters ready to fight.

The difference between 2020 and 1944 is the power of the party leadership, which is much reduced today. And unlike Bob Hannegan in 1944, today’s DNC chair, Tom Perez, cannot claim to speak for a sitting Democratic president. Interventions by Barack Obama or Nancy Pelosi on behalf of Biden will no doubt anger Sanders supporters, but there is neither a case based on precedent nor one in principle for a hands-off approach by the so-called establishment.

Fielding a far-left candidate, Democrats are likely to hand Donald Trump, enabled by an obeisant Republican Congress, another four years to undermine America’s cohesion at home and its standing abroad. The country needs an alternative to Donald Trump, and the Democratic Party needs firm, competent, and — yes — moderate leadership to deliver it.

Benn Steil is director of international economics and the historian in residence at the Council on Foreign Relations, as well as the author, most recently, of “The Marshall Plan: Dawn of the Cold War.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.