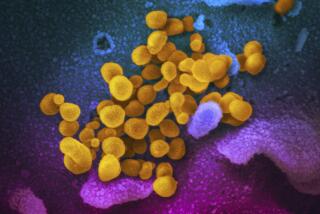

Editorial: Despite Trump’s chloroquine hype, we’re still waiting for a ‘game changer’ cure for COVID-19

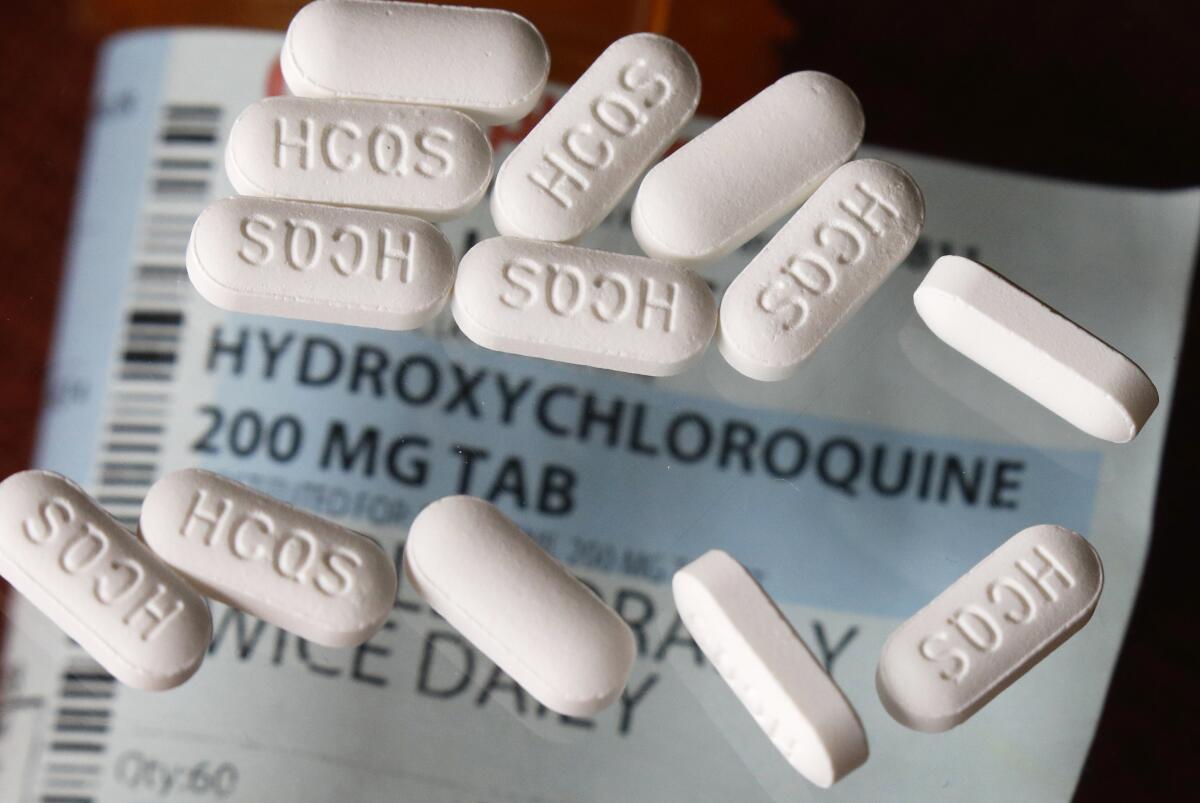

It’s been nearly four weeks since the U.S. Food and Drug Administration gave an emergency blessing to the use of two anti-malaria drugs for the treatment of COVID-19, setting the stage for the stockpiling and distribution of millions of doses. But so far, the drugs have fallen far short of President Trump’s repeated promotion of them as potential “game changers.”

For the most part, studies and clinical experience haven’t shown the hoped-for results of lowered death rates or quicker clearing of the novel coronavirus with chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine. The drugs’ side effects — most notably, dangerous heart problems — were troubling enough that a research effort in Brazil changed its protocol to avoid giving high doses, and Sweden has warned hospitals against using it to treat COVID-19. A newly released analysis of its use in veterans hospitals found no benefit. In fact, patients treated with hydroxychloroquine plus the usual therapies were more likely to die than those who received only the latter.

That’s not to say the drugs, whose anti-inflammatory capabilities make them useful in treating auto-immune diseases, are necessarily hapless against COVID-19. The more rigorous studies we need haven’t been completed, and it’s unknown whether treatment might be more effective at certain stages of the disease than at others — at least one study indicated that taking the drugs in early, milder stages might be helpful. In a pandemic with no vaccine or known treatment, it could be that trying something is better than trying nothing — as long as there is solid reason to think that the benefits will outweigh the risks.

But the rush to prejudge one drug or another as a possible magic bullet can be dangerous to our health. And now a vaccine expert has been ousted from his job as the head of a federal agency tasked with speeding the development of drugs and other medical responses to pandemics, apparently because he said that very thing. Dr. Rick Bright had thwarted Trump by refusing to push for widespread use of the anti-malarial drugs and calling for a scientifically sound approach to tackling the virus.

“Contrary to misguided directives, I limited the broad use of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, promoted by the administration as a panacea, but which clearly lack scientific merit,” Bright said.

Something similar happened with a rapid test for the novel coronavirus put out by Abbott Laboratories. The president hyped the tests, unboxing one before cameras and pronouncing it “an incredible system.” But the tests were plagued by supply-chain issues for needed components and then were found to be giving false negative results in certain situations, which could mean that infected people were out and about when they should have been quarantined.

The problem isn’t with trying an off-label use of a drug for a disease whose death toll mounts every day, or with helping companies speed the process of developing badly needed diagnostic tests. Decisive measures are needed in times of emergency. But political leaders should refrain from instilling unrealistic hope by boosting one possible treatment above all others, backed by precious little evidence. Especially when inadequate steps were taken to preserve enough of the drugs in question for the patients who really need them: people with lupus and rheumatoid arthritis.

The two drugs quickly became a political rallying cry. Many Trump supporters and conservative media became early and vociferous advocates for the anti-malarials, while liberals expressed ongoing reservations about the many weaknesses of a French study that had been cited as proof of the drugs’ worth.

Fortunately for everyone’s health, scientists went ahead and did what scientists do: Instead of heeding the president’s single-minded promotion, they have been testing numerous drugs. There have been recent reports of promising results with remdesivir, an antiviral drug meant to attack a virus’ ability to replicate — as well as a recent study that went in the opposite direction. Other medications being tested prevent overreactions of the immune system, which have been implicated in the most severe cases of the disease.

Again, it is far too early to say whether either or both of these drugs, or any of the others being tested, will make a serious difference in the number of severe illnesses or deaths. More robust answers should be forthcoming over the next month or two. But Trump made a grave mistake by heavily and repeatedly promoting products for which there was too little evidence.

Trump’s rashness and oversimplification of complicated issues are familiar qualities, but this time he’s playing with mortality rates and the desperate hopes of a fearful nation. The job of the president is to follow the science, not the other way around.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.