Op-Ed: A one-in-a-million, Tarzan-tree-swing, busted-knee infection

On a Tuesday in January, at that glowy pre-dinner hour when kids take their final turns around the backyard, my 11-year-old son stepped through the living room with blood pouring from an open flap on his right knee.

“I’m fine,” he insisted. He has perfected an admirable nonchalance under the guidance of my anxious mothering.

“Go show your dad,” I said, relieved that my husband, a pediatrician, was also home.

This has been our pattern at other medical crossroads with our son — the time he split his chin open, the time I discovered a bloated tick embedded in his shoulder, the time he fainted after an under-the-covers iPad session deprived him of oxygen — Mom quietly vibrates with concern, Dad handles it, and everything works out.

A tree swing, a dry ravine in our backyard, and a little too much confidence were the culprits this time. Our son hung on to the swing Tarzan-style and then let go where his drop would be plumb into the deepest part of the ravine. The sheer force of impact of knee on hard dirt busted open the skin. The wound would require five staples, and there would be a scar.

“The price of a happy childhood,” his dad said.

But neither my high-frequency worry nor my husband’s well-trained medical senses could have detected the invisible clostridium bacteria that had infiltrated the wound. Clostridium is the bacteria that causes gas gangrene and necrotizing fasciitis (nec-fasc in medical parlance). It lives in dirt everywhere. Mostly humans and clostridium coexist without incident, but there’s always a one in one in a million, and this time our son was it.

The next evening, our son was in the emergency room of the community hospital where his dad works, in pain and in need of antibiotics. The infection didn’t abate, and soon enough he was barely conscious in a helicopter en route to Valley Children’s Hospital in Fresno, where a surgical team would try to save his leg.

There wasn’t enough room or weight allowance on the helicopter for my husband or me, so we trailed two hours behind, navigating the two-lane roads that connect California’s Central Coast to Fresno. We called family. We asked them to pray.

When my sister and her husband sounded tentative, like they weren’t sure their prayer muscles were strong enough to reach from Louisiana to California, I told them what I had said to my son as they strapped him onto a stretcher and loaded him into the helicopter: We can do hard things. I couldn’t remember where this quote had come from. JFK? MLK? RBG? No matter, crises don’t require bylines.

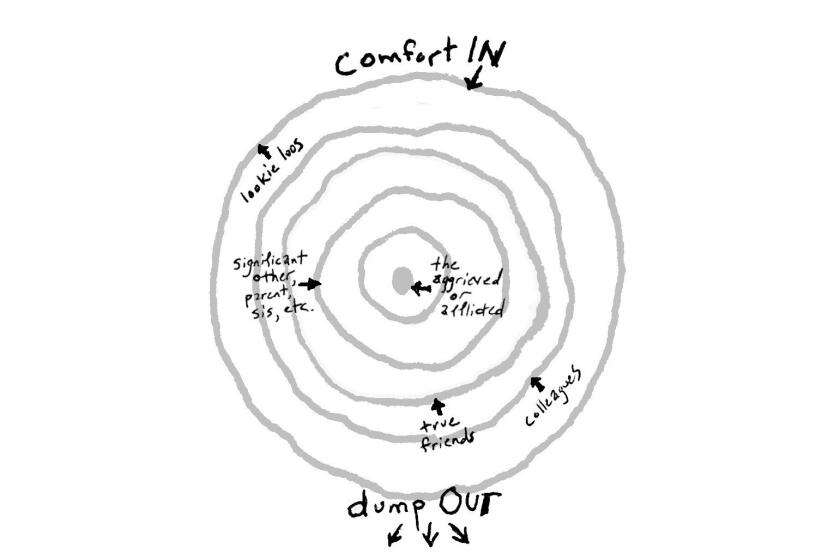

How not to say the wrong thing

Our son’s two surgeries went much better than expected. As long as the infectious disease team could figure out the proper antibiotic regimen, he would keep his leg. It took four weeks, but eventually they did. And he did.

Even with my husband’s hospital shifts, which exhausted all of my viral risk tolerance, we had assiduously avoided COVID-19 for a year. When the first signs of infection showed up in our son’s knee, I didn’t accompany him to the emergency room. Too iffy.

How quaint and faraway that abundance-of-caution decision seemed once I moved into his hospital room at Valley Children’s. We had COVID-infected neighbors on the surgical floor where we spent most of our nights. It wasn’t ideal, but if 2020 had taught us anything, it was to do our best under the circumstances. And if we forgot what “do your best” looked like, we could watch it on display every day at the hospital.

There was the operating room nurse who promised me that my son would be his son until he could return him safely to me in the intensive care unit. The patient front desk attendants who asked everyone who entered the hospital the COVID questions, day and night, over and over. The custodian who dubbed my wan, swollen, long-haired boy Princess, which my son took as the compliment it was. The baristas at the Starbucks downstairs who weren’t allowed tips but always remembered my London Fog tea latte anyway. The families bravely walking left to the palliative care unit as I kept going straight to the wing where patients recovered. The surgical physician’s assistant who taught my son to flip his crutches upside down and use them as stilts.

My son’s recovery continued once we got home (COVID-free, incidentally), thanks to a cocktail of antibiotics delivered via a line threaded from his upper arm to somewhere freakishly near his heart. Still, it was slow — steps forward, back, on the diagonal. There was an allergic reaction, anemia, another fall on the knee with more blood, night terrors, too many episodes of “The Office,” and many more mantras.

He got there.

It’s tempting to compare my son’s infection and his road back to health to the world’s current state of recovery, and I embrace the comparison because doing so shores up my endurance. Recovery is a nonlinear discipline. You take the long view. You count milestones, not days. Forward, back, on the diagonal. You do your best. You get there.

Sara Roahen writes, edits and teaches in San Luis Obispo.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.