Op-Ed: Refrigeration alone can’t solve the ‘last mile’ problem for COVID-19 vaccines

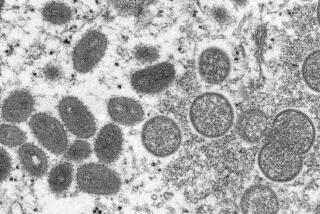

The COVID-19 pandemic is far from over. The Delta variant that devastated India has spread worldwide — and the next variant could be even more deadly. The pandemic will continue unchecked unless we support campaigns in fragile states such as South Sudan and Yemen to get more people vaccinated.

But vaccine availability does not automatically translate into shots in arms. The final stretch of a vaccine’s journey to its destination can involve complex logistics, including keeping it at a consistent cold temperature during transportation — the “cold chain.” Maintaining the integrity of this chain can be especially challenging when delivering medicines to remote areas mired in conflict and instability. Other barriers, such as extreme weather and displacement caused by conflict and climate change, can arise unexpectedly.

Nongovernmental organizations, or NGOs, can ensure that vaccine doses make it from airports to arms — using some of the same infrastructure, knowledge and clinical staffers that the sector has used to help eradicate wild polio in Africa, provide cholera vaccinations in Haiti, treat malaria in Yemen and battle Ebola in Africa. This same foundation could help to deploy a newly approved malaria vaccine or other new medicines.

However, last-mile delivery involves more than logistics and cold-chain support. There also is the need to counter misinformation and vaccine hesitancy.

Communities themselves must embrace vaccination programs to reach the needed levels of immunity. Unfortunately, the experience of NGOs has shown that populations in conflict zones and humanitarian aid settings don’t always embrace preventive measures such as masking and vaccination. Therefore, merely making vaccines available in these regions won’t be enough. Addressing hesitancy toward vaccination and educating communities on preventive measures requires a community-centered approach that engages hearts and minds.

For example, International Medical Corps — the humanitarian aid organization that I lead — recruited and trained community volunteers in Somalia at the onset of the pandemic to identify myths and misinformation there, and to counter them with accurate information. We set up a hotline that enabled community members to discuss with our staff the rumors they had heard. We eventually got feedback from 5,625 people, many of whom asked about home remedies — for example, whether garlic or black pepper could cure or prevent COVID-19.

We also produced informational videos that played in health facility waiting areas, went door to door sharing COVID-19 information and supported a popular call-in radio program hosted by a doctor to answer COVID-related questions and correct misinformation about the disease. Since its launch in June 2020, this wide-ranging campaign has reached almost 850,000 people with accurate information about the virus and helped build confidence in the vaccines. A survey that we conducted in February showed that 89% of the target population could recall two or more protective measures against COVID-19.

In our studies of vaccine hesitancy around the world, we’ve seen hesitancy higher in three groups: refugees and other displaced people; women; and young people. The first two groups — who feel marginalized and disconnected from the healthcare system — lack confidence in the efficacy, safety and administration of the vaccine. Measures like the ones described above help increase confidence in vaccines and the healthcare system.

For younger age groups, the main issue is complacency. They feel that they are healthy and don’t need the protection that the vaccine provides. And they’re not alone — with the pandemic projected to continue well into 2022, many people are tired of quarantines, of wearing masks and of the promise posed by vaccines that they believe may never reach them. To break through this complacency, we don’t just bring vaccines to vaccination centers. We make it convenient for people to come to these centers.

In Azraq and Zaatari refugee camps in Jordan, a full-spectrum, community-based approach — including registering people for vaccines, providing medical prescreening and transportation to vaccination centers, educating communities about the virus and administering vaccines — has directly resulted in more shots in arms.

To overcome hesitancy, we must instill confidence, battle complacency and provide convenience. But there is another “C” involved here: cash. Donors must invest now in vaccine delivery in low- and middle-income countries to ensure that future campaigns are effective — and to discourage future variants. In addition, humanitarian aid groups must be included in setting distribution strategy with the U.N. and national governments. Otherwise, vaccines could spoil in warehouses, and the pandemic could go on indefinitely.

Nancy A. Aossey is president and chief executive of International Medical Corps.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.